University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

For a digital version of this book, see the press website.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2011 by the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grayson, Donald K.

The great basin : a natural prehistory / Donald K. Grayson. Rev. and expanded ed.

p. cm.

Rev. ed. of: The desert's past. c1993.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-26747-3 (hardback)

1. Geology, StratigraphicPleistocene. 2. Geology, StratigraphicHolocene. 3. GeologyGreat Basin. 4. PaleontologyGreat Basin. 5. Indians of North AmericaGreat BasinAntiquities. 6. Paleo-IndiansGreat Basin. 7. Great BasinAntiquities. I. Grayson, Donald K. Desert's past. II. Title.

QE697.G8 2011

508.79dc22 2010052100

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997)(Permanence of Paper).

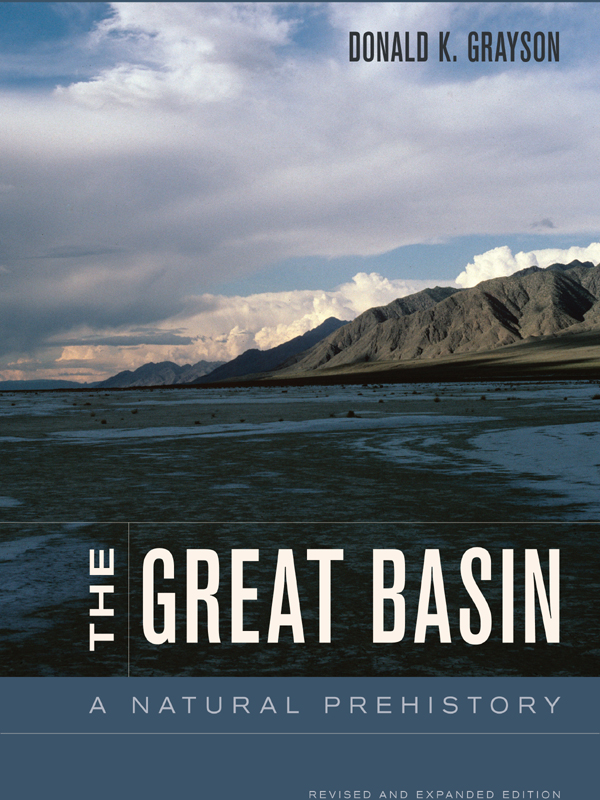

Cover image: Black Rock Desert, Nevada. Photo by the author.

For Barbara, who was my life

PREFACE

Most North Americans grow up knowing that parts of our continent were once covered by glaciers, that now-extinct mammoths and sabertooth cats walked the same ground on which we now walk our dogs, that people discovered North America long before Columbus stumbled across it. Most of us acquired this knowledge so casually that, if we happen to be asked exactly when these things occurred, we have no real answer. We would probably know that mammoths looked like elephants, but not that they became extinct about 11,000 years ago in North America. We might know about Ice Age glaciers and still not know that the maximum expanse of the most recent glaciation of North America occurred about 18,000 years ago. We might just shrug if asked when people first got to the Americas.

Answers to these questions are easy to learn. It takes no great insight, and little effort, to register the fact that mammoths became extinct in North America about 11,000 years ago. It is, however, harder to grasp the nature and magnitude of change that has occurred throughout North America during and since the end of the Ice Age.

We tend to assume that landscapes and the life they support are relatively permanent affairs unless human activity modifies them. We are not surprised when the farmland that surrounds the town we grew up in gives way to subdivisions and shopping malls: that kind of change we are used to and have come to expect and perhaps regret. But it is very surprising to learn how ephemeral the assemblages of plants and animals that surround us today really are and, in most cases, how recently those assemblages came into being. The brevity of our lives easily misleads us into thinking that the way things are today is the way they have been for an immense amount of time. It is even easier to be misled into thinking that things are the way they are now because they have to be that way.

Until recently, life scientists attributed far greater stability, longevity, and predictability to biological communities than those communities actually possess. One of the great scientific gains of the past few decades is the recognition of the vital role that history has played in forming the plant and animal communities that now surround us, the recognition of how unpredictable changes in those communities can be, and the recognition of how fleeting their existence often is. Plant and animal communities appear stable and real to us only because we do not live long enough to observe differently. Bristlecone pines, which do live long enough, know better.

Today, most life scientists, especially those whose work has any significant time depth, also know better. Although we may not live as long as bristlecone pines, we do have techniques for extracting information about earth and life history that can tell us not only what specific landscapes were like in the past but also precisely when in the past they were like that. Even though we have made less progress toward understanding why they may have been that way, we have come a long way in this realm as well. We know now enough about at least the late Ice Age and the times that followed to be able to provide fairly detailed environmental histories for nearly all parts of North America.

In this book, I provide such a history for the Great Basin. I define the Great Basin in multiple ways in , but here, suffice it to say that the Great Basin centers on the state of Nevada, but also includes substantial parts of adjacent California, Oregon, and Utah. My goal is simple: to outline the history of Great Basin environments from about the time of the last maximum advance of glaciers in North America to the arrival of Europeans and their written records. In so doing, I hope to convey the dynamic nature of the landscapes and life of this region.

During the late Ice Age, camels lived near what is now Pyramid Lake in northwestern Nevada; massive glaciers existed in the high mountains of eastern Nevada; substantial lakes lay in settings as far-flung as Death Valley and the Great Salt Lake Desert; trees grew in the valleys of the Mojave Desert of southern Nevada. The camels, glaciers, lakes, and low-elevation trees are now gone. Today, pinyon-juniper woodlands drape across millions of mountain-flank acres in the Great Basin, and saltbush vegetation is common in many of the valleys that lie beneath the woodlands. To the south, the oddly attractive creosote bush is a dominant shrub in the valley bottoms. This is a remarkably recent state of affairs, and a prime goal of this book is to document these facts and to discuss why they are so.

It was not hard for me to decide what to cover here: glaciers and lakes, shrubs and trees, mammals and birds, the people. Others might have chosen a different set of topics, in some cases broader, in others narrower. The set I have chosen, however, not only strikes me as important but also reflects my background as a scientist trained in archaeology, vertebrate paleontology, and paleoecology. Someone who knows more about insects, leeches, and snails would have written a different book. In fact, I wish they would, since I would like to read it. The content of this book also reflects the fact that it has been my great fortune to know and to work with most of the people whose work is discussed here.

Deciding on the temporal coverage was more difficult. That this book would deal with the past 10,000 years was clear from the outset, as was the fact that it would also cover the waning years of the Ice Age or Pleistocene. These are, after all, years that were critical to the formation of the plant and animal communities of the Great Basin as we know it today. They also happen to be the years on which much of my own Great Basin work has focused. In the end, I decided to begin my coverage at about 25,000 years ago, though sometimes earlier and sometimes later. I made that decision both because 25,000 years ago allows me to discuss the Great Basin prior to and during the Last Glacial Maximum, and because our knowledge of Great Basin environments tails off sharply before that date.

Today, the term natural history is often used in a very general way to refer to the things that life and earth scientists study. That is the way I use it here, modifying it in the title to indicate that this book deals primarily with events that took place prior to the times for which written records are available. Thus, this book is very much a natural prehistory, dealing with the landscapes of the Great Basin, and the life it supported, during the past 25,000 years or so.