Cities, Sagebrush, and Solitude

Urbanization and Cultural Conflict in the Great Basin

EDITED BY

Dennis R. Judd and Stephanie L. Witt

UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA PRESS

RENO & LAS VEGAS

THE URBAN WEST SERIES

Series Editors: Eugene P. Moehring and Amy L. Scott

University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

Copyright 2015 by University of Nevada Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cities, sagebrush, and solitude : urbanization and cultural conflict in the Great Basin / [edited by] Dennis R. Judd, Stephanie L. Witt.

pages cm. (The urban West series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87417-969-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-87417-970-5 (e-book)

1. UrbanizationGreat Basin. 2. Urban policyGreat Basin. 3. Sustainable urban developmentGreat Basin. 4. Great BasinEnvironmental conditions. 5. Great BasinEconomic conditions. 6. Great BasinPolitics and government.

I. Judd, Dennis R. II. Witt, Stephanie L.

HT384.U52G743 2014

307.760979dc23 2014035961

Preface

Cities, Sagebrush, and Solitude addresses a much-neglected topic: the environmental consequences and political conflicts arising from the recent and rapid urbanization of the largest of the four deserts of North America, the Great Basin. In recent decades the rapidly spreading urban agglomerations within this arid landscape make it, in statistical terms, the fastest-growing urban region in the United States. The four metropolitan areas situated at the cardinal points of the Basins rimBoise, Reno, Salt Lake City, and Las Vegasmust cope with the problems associated with rapid growth, but attempts to do so provoke conflict between urban residents and the people who live in the thinly populated desert outback. In the Great Basin, policies to address the environmental and resource limitations imposed by the desert environment may be incompatible with a deeply entrenched political culture that resists all cooperative or governmental effort. The alchemical mixture of three ingredientscities (which are morphing into sprawling metropolitan regions), sagebrush (the ubiquitous signifier of aridity and resource scarcity), and solitude (which has nurtured a libertarian political outlook)makes the Great Basin a compelling place to study. Each chapter of this book traces the way that the tensions among cities, sagebrush, and solitude inform contemporary policy debates and public policies of the region through an analysis of the environmental stresses connected to economic change, resource extraction, land management, and urban development.

The conversations that created the community of scholars who contributed to this book took place at two conferences held on the campus of Boise State University in 2011 and 2012. Nearly all of the participants had written about the West, but only three of them had previously focused their research specifically upon the Great Basin. These conferences provided an opportunity to engage in the kind of animated give-and-take necessary for giving a consistent thematic structure to a project as unique as this one. The tenor of those lively exchanges informs our approach to the subject matter. The editors encouraged authors to step a bit outside their academic roles and write for a diverse audience of scholars, policy makers, and educated readers. We believe the topic of the book will interest scholars across several disciplines (especially social scientists and urban and policy specialists), plus scholars and informed readers interested in the history, politics, culture, and environmental issues of the American West. This book should be especially appealing to residents and policy makers living in the Great Basin, one of the most beautiful, sometimes desolate, and misunderstood ecological regions of the United States.

We appreciate the generous hospitality provided by Boise State University for the two conferences that brought scholars together from six western universities. In particular, we want to express our thanks to Melissa Lavitt, who was then dean of the College of Social Sciences and Public Affairs at Boise State University, for offering enthusiastic encouragement at every step of the way. This book would not have been possible without the critical support of Dean Lavitt and the college.

The Last Urban Frontier

DENNIS R. JUDD AND STEPHANIE L. WITT

IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, a historic redistribution of the American population brought into being the New American West. The opulent, energetic, mobile, and individualist cities of Southern California seemed to perfectly project Americas national future,

Despite its vast expanses of thinly populated desert, the Great Basin is the fastest-growing urban region in the United States. In only a fourteen-year period from 1990 to 2004, the population of the Great Basin Desert increased from 2.9 to 4.9 million people.

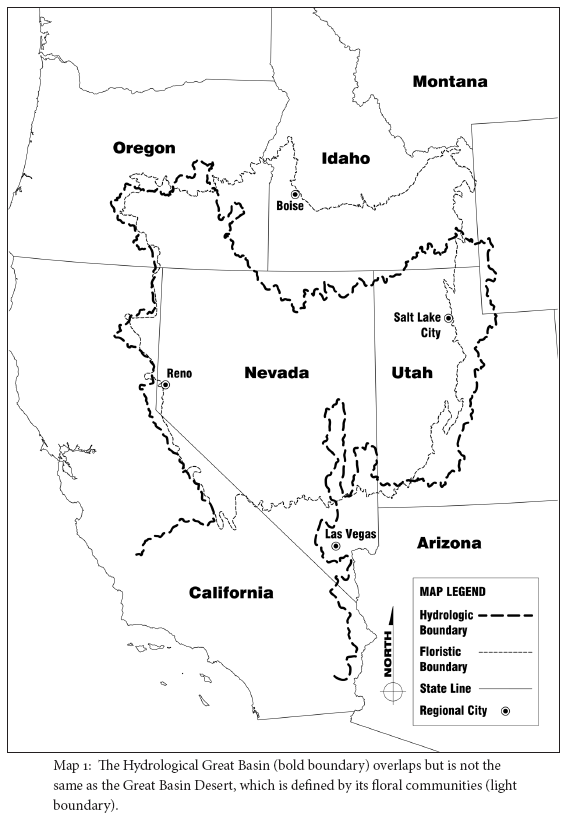

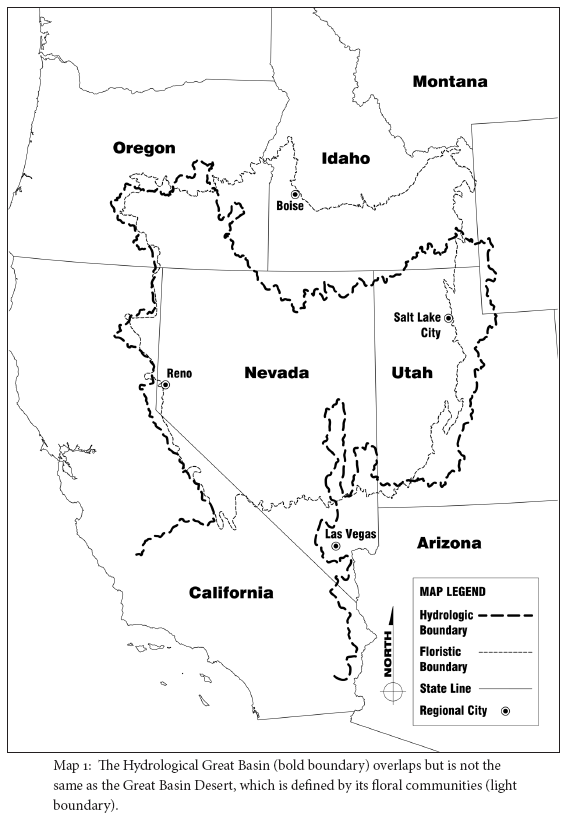

The Great Basin is the largest of the four deserts of North America (the others are the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan), and it would not seem to be a friendly place to build cities. In 1843 explorer John C. Frmont coined the term the great basin to refer to a desiccated inland region where the water drains inland rather to the sea. By his reckoning this vast area stretched from a range of mountains in southern Idaho and a portion of southeastern Oregon almost to Baja California (see Extremes of aridity, heat, cold, and alkali are the main ingredients that produce a desolate and forbidding landscape.

Extreme aridity imposed an oasis pattern of settlement that differed significantly from the American historical experience. Instead of the small towns and fertile fields that marked westward expansion and progress in milder climates, the towns and tiny hamlets of the Great Basin were widely scattered, each located wherever a water source and a patch of arable land made a permanent human presence possible. For this reason, rural does not work well to describe the lightly settled reaches of this desert region; terms such as frontier and outback come more easily to mind.

The Great Basin is littered with ghost towns, physical reminders that people have found it difficult to permanently settle there. Environmental limitation was the ultimate lesson of the harsh, empty, desert country, and the ethos of those people who endured was extractive rather than nurturing. In the mining era, as soon as the ore played out towns that had popped up almost overnight vanished just as quickly. For the Mormons, a unifying theology produced the disciplined cooperation needed to make the desert bloom in a few irrigated slopes and valleys along the Wasatch Range. In three other places on the Basins rim, the history of stymied progress ended in the twentieth century, when massive federal reclamation projects brought water to the foot of the Sierra Nevada at Reno, dams and canals to the Snake River Plain and, in the late 1950s, when Las Vegas completed a pipeline to Lake Mead, a meandering 110-mile-long reservoir backed up behind Hoover Dam, one of the largest dams ever constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation. These were the four areas of the desert where cities of a significant size might prosper.