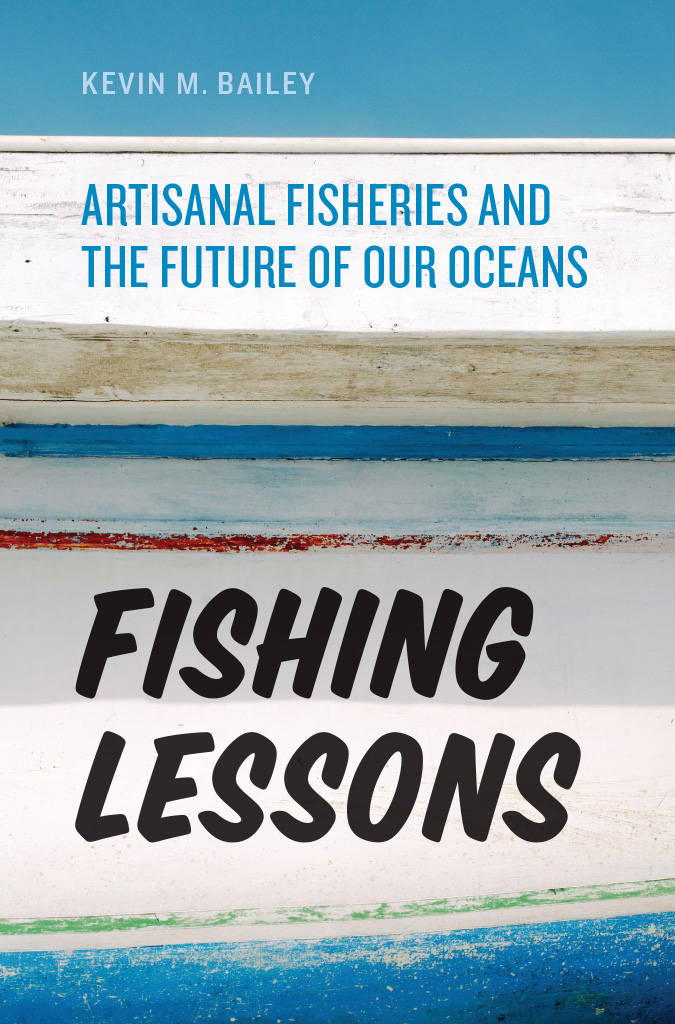

Fishing Lessons

Fishing Lessons

Artisanal Fisheries and the Future of Our Oceans

Kevin M. Bailey

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by Kevin M. Bailey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30745-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-30759-6 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226307596.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bailey, Kevin McLean, author.

Title: Fishing lessons : artisanal fisheries and the future of our oceans / Kevin M. Bailey.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039497 | ISBN 9780226307459 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226307596 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Small-scale fisheries.

Classification: LCC SH329.S53 B35 2018 | DDC 338.7/6392dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039497

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

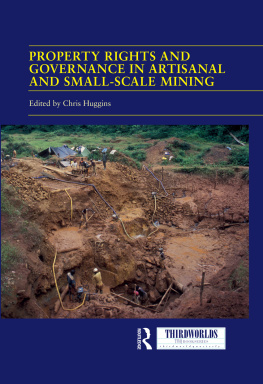

I watched Tonino Calise mend his nets in the afternoon sun. His leathered fingers braided the twine without the need of thought, or interruption. With a cigarette dangling from his lips like James Dean, he squinted up at me as I scribbled in my notebook. He offered brusque answers to my questions, then turned back to his work.

An Italian friend had introduced me to Tonino and translated for me as we talked about the small-scale artisanal fisheries of Ischia, a small island in the Bay of Naples. I was in Ischia trying to shed my scientists skin and learn about the human side of fisheries. During my thirty-five years as a biologist experimenting in the laboratory, working on research ships at sea, and then more and more sitting in front of a computer screen, Id had little exposure to the lives of fishermen.

Fishing is an ancient way of life; its citizens now are graying and disappearing, washed over by the changing world around them. The life of a small-scale traditional fisherman is challenging. This is rough, hard work. Not many young people are attracted to it. While a life of fishing offers independence, it can be lonely. But for those who are drawn to the boats, the salt of the ocean is in their blood, and the rhythm of the sea is never far away.

What manner of person ventures out in his boat to roam the sea, face danger, and suffer hardships? If traditional fishermen disappear, what happens to their acquired knowledge of the sea, their know-how of the boat, their expertise in catching fish? These are skill sets that will be hard to replace. Are small fisheries like Toninos worth saving, or are they relics of the past? Do we value more plentiful and cheaper fish, or is it important to preserve a way of life? Are so many traditional fishermen the source of the overfishing problem, or can they be part of the solution for the oceans troubled fisheries?

Fishing from his small open boat in the late afternoon, Tonino casts a small gillnet called a schietta into the sea. He usually catches Mediterranean hake, monkfish, mackerel, the occasional swordfish or tuna, and some other small species. In the early morning he retrieves his net and chugs back to the harbor at daybreak to sell his fish in the local market.

Tonino told me that he catches fewer fish now than in years past. Hes had to resort to using a larger net. He blames the big trawlers from Procida, a small island nearby, and from the mainland port of Pozzuoli for catching too many fish, thereby leaving few behind for the other fishermen.

The island of Ischia sits on the edge of a protected marine reserve in the Mediterranean. I asked Tonino if the reserve has helped him as a fisherman. He responded with a laugh, sweeping his hand through the air as if to shoo away a fly, and remarked that the marine reserve has had little impact on the availability of fish in the area. He said the regulations in the reserve are lax and often not enforced. Everyone fishes there. The refuge is mainly present to attract scuba-diving tourists. When I mentioned the governance of fisheries by catch limits and individual quotas, the management tools put forth by academic scientists and government administrators to prevent overfishing, he scoffed. It wont work here. There are too many fishermen, and they dont keep records.

Later in the evening when darkness fell, the air was muggy and I was restless. I opened the windows of my small rented apartment overlooking the harbor. The village of Lacco Ameno has become a tourist hot spot for the yachting crowd. Shoreline development has accommodated them, while decimating the local fisheries by destroying habitat and creating pollution. In the night air, at least three bands competed for sound space. The dissonance continued until the wee hours. One band played Mexican love songs; another was, I think, a klezmer jazz band with clarinet, tambourine, and thundering bass guitar. Floating on top of it all was a sultry voice singing Italian pop songs. My thoughts turned over Toninos dismissal of the management measures offered by fisheries biologists (like myself) and other well-meaning desk jockeys astride Aeron chairs, often ignorant of the reality on the waterfront. The weaving strains of music hinted of a metaphor for the discord among the fishermen, government administrators, and scientists.

Not long after I returned home from Italy, my friend from Ischia wrote me a note to say that Tonino didnt return with his catch one morning. They had found his boat adrift. He was fishing alone when the heart attack struck, and he died on the ocean, doing what he loved. My all-too-brief encounter with Tonino symbolized a fading human legacy.

Figure 1. Fisherman Tonino Calise mending his nets in the harbor of Lacco Ameno on the island of Ischia, Italy. Photographer: K. Bailey.

Plight of Traditional and Small-Scale Fishermen

Interpretations of traditional fisheries range from traditional subsistence fisheries to harvesting operations where fishermen use only traditional gear or even unpowered vessels. Some definitions involve the size of boat used in the fishery. Sometimes the terms artisanal fishery and small-scale traditional fishery are used interchangeably. I think a modern and practical definition would incorporate the ownership, scale, method of harvesting, and quality of the product delivered. For this book, I define a traditional fishery as small in scale, owner-/family-operated, delivering a craft product to the market. Often the method of harvest is customary. But since virtually all fishing gear being used now was available in some form prior to the Industrial Revolution, most gear is included here. Vessel size is generally less than twenty meters in length.

There is a blurry line between artisanal and small-scale traditional fishermen. An artisanal fishery is thereby a subset of small-scale traditional fisheries, although the fishermen of both groups often face similar problems.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).