Copyright 2019 by Daniel Pauly

Foreword copyright 2019 by Jennifer Jacquet

19 20 21 22 23 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books Ltd.

greystonebooks.com

David Suzuki Institute

davidsuzukiinstitute.org

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77164-398-6 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-77164-399-3 (epub)

Editing by Nancy Flight

Copyediting by Rowena Rae

Cover design by Will Brown

Text design by Belle Wuthrich

Greystone Books gratefully acknowledges the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples on whose land our office is located.

Greystone Books thanks the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada for supporting our publishing activities.

CONTENTS

by Jennifer Jacquet

FOREWORD

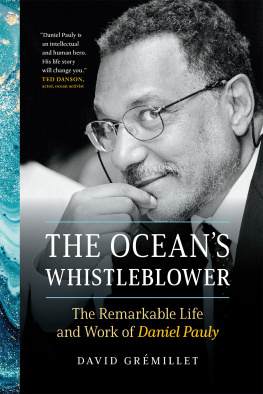

MANY PEOPLE FIRST meet Daniel Pauly during one of his frequent speaking or film appearances, efforts he wryly refers to as his fieldwork. My first impression of Daniel came through his writing. In 2003, when I was taking a course in marine ecology, I read his article Fishing down the marine food web, published in Science in 1998, and with the first sentence, I became fascinated by the way Daniel thinks. The article begins: Exploitation of the ocean for fish and marine invertebrates, both wholesome and valuable products, ought to be a prosperous sector, given that capture fisheriesin contrast to agriculture and aquaculturereap harvests that did not need to be sown. The premisethat fish and invertebrates are products with which to make an economic sector prosperousseems a little suspect to me now, and, as a pioneer in ecosystem-based approaches to fisheries, Daniel most likely would not write that line the same way today. But there is nonetheless something in his writing, as there is in all the essays in this book, that indicates Daniel has something to say and it matters to him how he says it.

Daniels style can be partly attributed to the fact that, unlike most fisheries biologists, he has embraced both the humanities and the social sciences. He is especially fond of history, probably because of his tendency toward big-picture thinking. Daniel is also a man of many countries, and it is with some embarrassment for all of us native English speakers who have been closely edited by him that he spoke French and German well before he spoke English, which he wields with greater precision than we do. When he returned the first draft of the first paper he and I worked on together, he had written good on it but then crossed that word out and written This will be good below it. There is much to admire in the exactness of his observations and his writing.

Daniel no longer uses the term harvest to refer to fisheries catches, just as he has recently abandoned the term stock (see the ). If we were to press him on this decision, he would have something clever to say, as he did when I once accused him of changing his mind about some issue, and, unfazed, he responded: Its the best proof I still have one. We all shed our conditioning and become willing to see the world in new ways at different rates, and Daniel is faster than most. That is also the benefit that a collection like this affordsa chance to see how its writer has evolved over time. In these essays, Daniel refers to the threefold expansion of fisheries that he and his research team have identified and quantified: fishing farther offshore, fishing deeper, and fishing for new species. Similarly, the threefold expansion of Daniels own thinking has fundamentally changed the fields of fisheries science and marine conservation, as well as the broader, public conversation.

First, Daniel expanded fisheries in space and time. He moved fisheries from a parochial endeavor in which every element is context- and species-specific and connected the dots to show us the benefits of considering fisheries as a global system. Because he had seen a lot of the world, Daniel was well positioned to think on a global scale, but he was also brave and tenacious enough to try to work that way too. I spent seven years with Daniels Sea Around Us project and saw firsthand that the ability to do quality work on a global level requires not only intellect but also mettle, as well as serious endurance for drudgery. Daniel also shifted fisheries research from its all-too-convenient baselines of 1980 or 1970 and challenged researchers to think about fisheries over longer time frames. When his colleagues hosted a celebration at the University of British Columbia for Daniels sixtieth birthday, ecologist Jeremy Jackson credited Daniels single-page essay on shifting baselines (see

Second, Daniel expanded fisheries science from a discipline dominated by industry concerns to one that considers multiple stakeholders. Instead of representing the interests of only the fishing industry, he works most closely with civil society groups. He pushed for the inclusion of small-scale fishers both in the global dataset and at fisheries negotiations. (At a talk where Daniel was asked why government subsidies favored industrial fisheries over small-scale fisheries, he responded: Because small-scale fishermen dont play golf.) Through ecosystem modeling and other scientific work, he also fought to include marine animals in the conversation. He has, for example, repeatedly defended whales against the accusation by whaling country representatives that they eat all of our fish (and therefore that we should kill them to increase global fisheries catches) with scientific evidence demonstrating that the distribution and consumption patterns of whales do not significantly overlap with the operating areas of, and the species exploited by, fisheries.

Third, Daniel has pushedto a lesser extent, but one that should not be overlookedfor fish and invertebrates not to be seen exclusively as seafood or commodities. He has asked that, as with whales, we consider fish not just as species but also as individual animals. Throughout his career Daniel has increasingly veered from the views held by many of his scientific colleagues who endorse a status quoone that Daniel, as scientist and as citizen, thinks is pernicious both for his discipline and for society at large. May we all aspire to this kind of critical thinking and courage.

On a final note, in Western society, particularly in the United States, science and scientists bear most of the burden of proof regarding the potential for negative impacts of new developments. Although, in theory, we should operate under a precautionary principle, in practice, scientists must demonstrate harm to the ecosystem, but extractive industries need not demonstrate their lack of negative impacts. Daniel has repeatedly shouldered this burden for all who believe that the interests of civil society, small-scale fishers, and the animals in the ocean should also be considered. This book is a tribute to his willing and adept work on behalf of this disparate group.