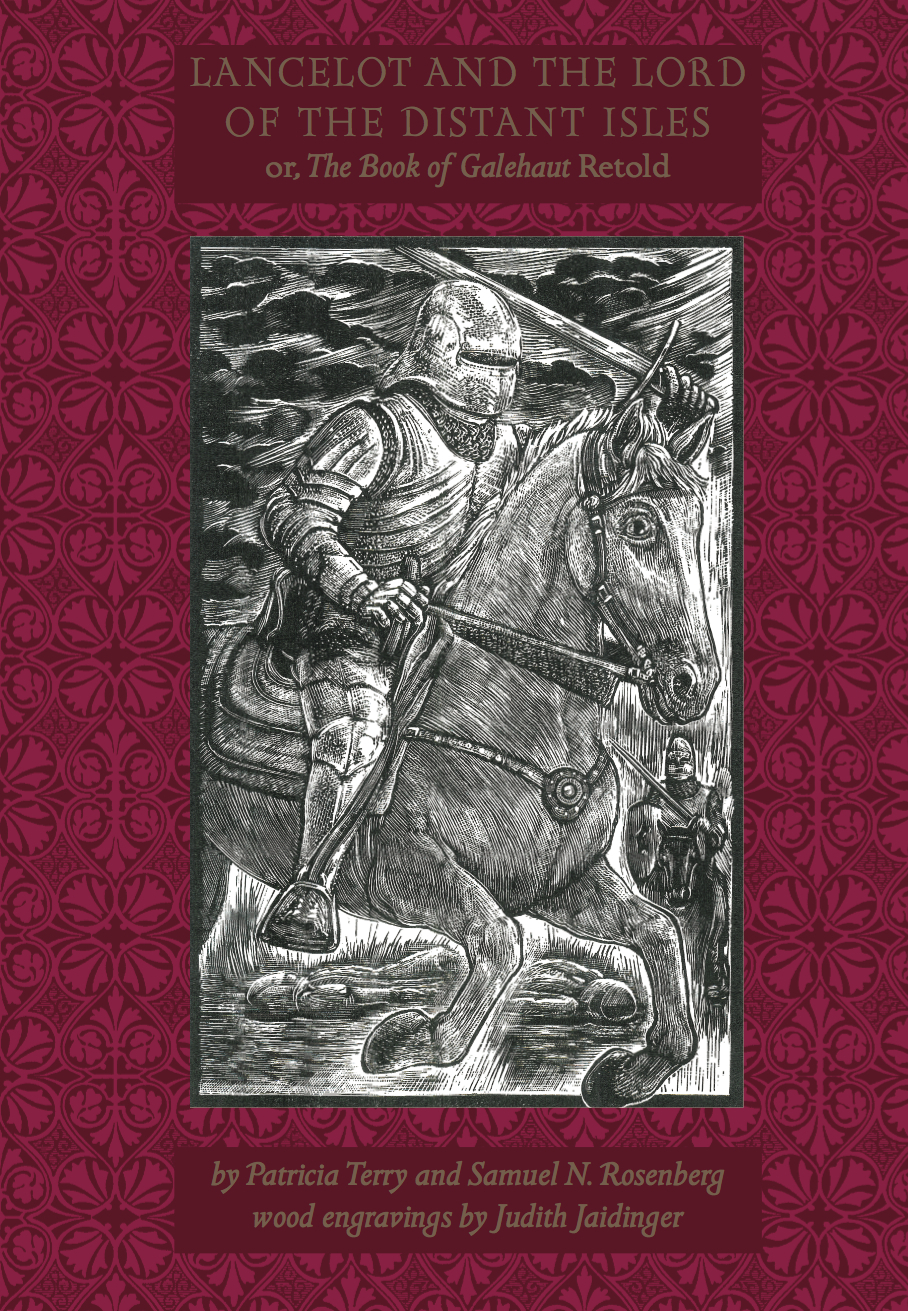

Patricia Terry - Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles

Here you can read online Patricia Terry - Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

O ne of the greatest distinctions of the Arthurian legend is the widespread longing that it be real. If Arthur did, in fact, exist, he was probably the leader of the native people of Britain, at a time when their lands were being invaded and settled by Saxons and other Germanic groups. (These newcomers would later be called the English.) Sometime toward the end of the fifth century, the Britons began to fight back. There was a decisive battle, and then, for perhaps half a century, the Saxons were held at bay. The memory of the chieftain responsible for that victory would have lingered long after the Saxons ultimate success. There must have been nostalgia for a time when extraordinary valor, combined with a sense of being in the right, had prevailed over formidable, and foreign, opponents. Such was the stuff of legends carried through Wales and across the Channel into Brittany by descendants of the Celtic Britons. Even today, there are autonomy-minded Bretons in France who evoke their lost leader, the once and future king. Chroniclers did not give him a name until the ninth century, but long before that he had come to be known as Arthur.

In the early twelfth century, when King Arthur was well established in chronicles, stories, and local traditions, Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote, in Latin, a largely imaginary History of Britain . From this source the most familiar aspects of Arthurs story were to be gradually elaborated, mainly in French: his birth, contrived by Merlins sorcery; the sword Excalibur, forged in Avalon; the Round Table and the knights who had their places at it; Gawain the loyal nephew and Mordred the rebellious son; Kay the seneschal; Guenevere, Arthurs queen. To Arthur came knights from many countries, forming a company of the elite. Women, Geoffrey wrote, in a suggestion of enormous consequence, would give their hearts only to the brave.

Arthur, in Geoffreys telling, is a great monarch. He conquers Saxons, Scots, Picts, in his own island, often with great cruelty, then makes war on Gaul, and finally attacks even Rome. His preferred city is Carleon, where he is crowned in an impressive ceremony attended by four kings. Arthurs armies are formidable, but he himself is always in the foreground, the greatest of warriors, capable of overcoming even a monstrous giant. He attracts worthy men by his reputation for valor, and is also celebrated for his generosity. When he ultimately falls in battle, it is only through the treachery of one of his own, Mordred, and it is suggested that there will be a wondrous healing of his wounds on the mythic isle of Avalon.

Geoffreys book, however fanciful, is in the form of a chronicle, purporting to be the translation of an ancient British source. Geoffrey is rightly credited, however, with being the father of Arthurian romance, fiction derived from his work as well as other sources and no longer composed in Latin. Chrtien de Troyes, writing in French verse, developed his own version of Arthurs court as a setting for plots which reflected contemporary interest in elegance of manners, youth and beauty, ceremonial festivities, the quest for personal glory, and love. This is the modern vision of Camelot, although Chrtien almost always placed the court in Carleon.

Instead of armies in which individual exploits are subordinated to the glory of the king, Chrtien gives center-stage to the knights themselves. They leave the court in search of adventures to test their valor, and often their quest is complicated by the rival demands of love. They work out their destinies alone, sending messages back to let Arthur know their progress. While they pride themselves on being members of his court, the king himself is essentially inactive.

Thanks to the Norman Conquest in 1066, Chrtien knew France and the land beyond the Channel as a reasonably cohesive cultural entity. But King Arthur was British, the symbolic ruler of a race that prevailed before both Normans and Saxons. His knights and vassals, on the other hand, were diverse in origin, and often had lands of their own. Although some have suggested a political motivation for Arthurs diminished role in Chrtiens portrayal, that lesser role may simply reflect the need to choose between the past deeds of an already powerful monarch and the present feats of his knights. An individual, riding out on his own, ready to confront whatever challenge may come his way, is the characteristic figure of romance.

Geoffrey was Welsh and spun his tale, in part, from Celtic folk stories imbued with the magic of a pagan mythology. In his History , Arthur has two hundred philosophers who read his future in the stars, and a cleric who can cure any illness through prayers. Above all, Geoffrey created the prophet and magician Merlin, centrally important to the career of King Arthur. Still, he was chary in his relation of what the French would call marvels. Chrtien proves more receptive. He gives us strange fountains, mysterious maidens bearing messages, companionable lions, hints that there exists another realm independent of our own and more powerful. This inheritance from lost Celtic tales is fragmentary in Chrtiens romances, but becomes more pervasive in the expansive French narratives that dominate vernacular romance in the early decades of the thirteenth century.

Chrtien seems to have been reticent about what later came to be called courtly love, a term invented by Gaston Paris in the nineteenth century. There is a faint trace of it in Geoffrey of Monmouths statement connecting the brave and the fair, but it was first elaborated, from yet ill-defined sources, by the lyric poets of southern France, the twelfth-century troubadours. Fundamental, and revolutionary, in this phenomenon is the belief that a man can be ennobled through striving for a womans love. A corollary assumed rather than logically necessary is that love is incompatible with marriage, because true love must be free of social constraint. Erotic passion, in antiquity, was considered a disaster, a curse from the gods, and the warriors of early medieval French epic poems had essentially no interest in women, except as a form of property. It was a radical transformation when, at least in literature, a knight could be regarded as lacking prestige unless he won the love of a noble lady. He would devote himself to performing heroic deeds, but at least as much to a discreet courtship of his beloved, in the hope that she would consider him worthy of her favor. Occasionally he might even be granted a transcendent physical proof of her acceptance. From this we derive the homage that Western literature has paid to passionate, adulterous, and, almost inevitably, tragic love ever since the twelfth century.

The Arthurian romances of Chrtien de Troyes, however, do not reflect this trend, since they most often are concerned with finding a means to reconcile the demands of a knights career with his desire for a happy marriage. The exception among his romances is a story of Lancelot called The Knight of the Cart , whose plot and meaning were both provided by the poets patron, Marie de Champagne, granddaughter of Duke William IX of Aquitaine, the first known troubadour, and daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine. It was she, presumably, who first imagined the exemplary knight in love with King Arthurs wife, Guenevere. Chrtien does not relate the beginning of Lancelots love for the queen but concentrates on a later episode in their relationship: the queen has been abducted, and Lancelot abruptly appears, already on his way to rescue her. The abduction of the queen seems to be a Celtic motif, and the heros name, Lancelot du Lac, may have had a Celtic source as well. Chrtien writes briefly of Lancelots having been raised by a fairy who gave him a magic ring, capable of distinguishing enchantments from realities. The fairy will come to help him whenever he is in need.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles»

Look at similar books to Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lancelot and the Lord of the Distant Isles and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.