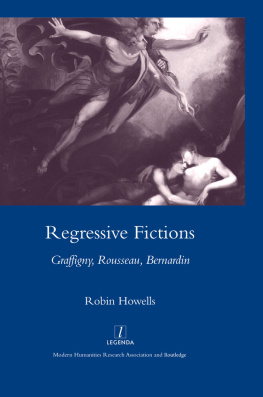

Howells - Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin

Here you can read online Howells - Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Abingdon;Oxon;New York;NY, year: 2017, publisher: Taylor & Francis (CAM);Routledge, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Howells: author's other books

Who wrote Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

REGRESSIVE FICTIONS

GRAFFIGNY, ROUSSEAU, BERNARDIN

LEGENDA, founded in 1995 by die European Humanities Research Centre of the University of Oxford, is now a joint imprint of the Modern Humanities Research Association and Routledge. Titles range from medieval texts to contemporary cinema and form a widely comparative view of the modern humanities, including works on Arabic, Catalan, English, French, German, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and Yiddish literature. An Editorial Board of distinguished academic specialists works in collaboration with leading scholarly bodies such as the Society for French Studies and the British Comparative Literature Association.

The Modern Humanities Research Association (MHRA) encourages and promotes advanced study and research in the field of the modern humanities, especially modern European languages and literature, including English, and also cinema. It also aims to break down the barriers between scholars working in different disciplines and to maintain the unity of humanistic scholarship in the face of increasing specialization. The Association fulfils this purpose primarily through the publication of journals, bibliographies, monographs and other aids to research.

Routledge is a global publisher of academic books, journals and online resources in the humanities and social sciences. Founded in 1836, it has published many of the greatest thinkers and scholars of the last hundred years, including Adorno, Einstein, Russell, Popper, Wittgenstein, lung, Bohm, Hayek, McLuhan, Marcuse and Sartre. Today Routledge is one of the world's leading academic publishers in the Humanities and Social Sciences. It publishes thousands of books and journals each year, serving scholars, instructors, and professional communities worldwide.

www.routledge.com

Chairman

Professor Martin McLaughlin, Magdalen College, Oxford

Professor John Batchelor, University of Newcastle (English)

Professor Malcolm Cook, University of Exeter (French)

Professor Colin Davis, Royal Holloway University of London

(Modern Literature, Film and Theory)

Professor Robin Fiddian, Wadham College, Oxford (Spanish)

Professor Paul Garner, University of Leeds (Spanish)

Professor Marian Hobson Jeanneret,

Queen Mary University of London (French)

Professor Catriona Kelly, New College, Oxford (Russian)

Professor Martin Maiden, Trinity College, Oxford (Linguistics)

Professor Peter Matthews, St John's College, Cambridge (Linguistics)

Dr Stephen Parkinson, Linacre College, Oxford (Portuguese)

Professor Ritchie Robertson, St John's College, Oxford (German)

Professor Lesley Sharpe, University of Exeter (German)

Professor David Shepherd, University of Sheffield (Russian)

Professor Alison Sinclair, Clare College, Cambridge (Spanish)

Professor David Treece, King's College London (Portuguese)

Professor Diego Zancani, Balliol College, Oxford (Italian)

Managing Editor

Dr Graham Nelson

41 Wellington Square, Oxford OXI 2JF, UK

legenda@mhra.org.uk

www.legenda.mhra.org.uk

Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin

Robin Howells

First published 2007

Published by the

Modern Humanities Research Association and Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

LEGENDA is an imprint of the Modern Humanities Research Association and Routledge

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Modern Humanities Research Association and Taylor & Francis 2007

ISBN 978-1-904350-86-6 (hbk)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, recordings, fax or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner and the publisher.

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

In the course of conceiving and writing this book I have benefitted from the work and conversation of a number of people, in particular Jonathan Mallinson, Jacques Berchtold, Malcolm Cook, Kate Astbury, and Philip Robinson. During its production, Graham Nelson of Legenda has been consistently both efficient and kind.

My personal thanks to Fe Ringham, Karen Lacey and Martine Roberts; and as always to Coral.

I am grateful for the support provided by Birkbeck, University of London.

The term regression I employ here primarily in its Freudian sense: a psychological retreat from adulthood, or social reality and genital sexuality, into an earlier if not primary stage of development. Broader support for my reading is offered in this preliminary section, which sketches some large perspectives and then points to indices of cultural change in the mid-century from which these works emerge.

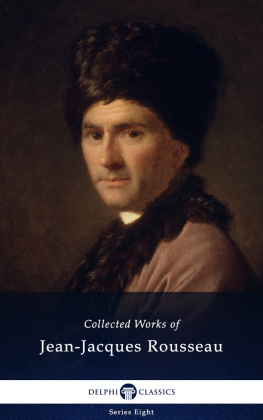

The 'rise of the novel' in the eighteenth century, notable in itself, is strongly characterized by the use of first-person forms. In memoirs and letter-novels alike, the new centrality of 'je' must reflect a new individualism and a new interiority in this period. We are at a further stage of what Charles Taylor calls 'the inward turn', which he traces in Western consciousness from St Augustine. In the eighteenth century (inaugurating Taylor's 'third stage') the source of self becomes Nature. Nature, we may say, is no longer to be seen as fallen, but increasingly, on the contrary, as the principle of moral good. That good is known rather less from traditional institutions Church, monarchy, social hierarchy or from the current ethos of sociability, and more immediately in the heart. Present society, if not society itself, is now identified as the source of corruption. Man is born innocent; and this opposition is mirrored in the discovery of the state of childhood. That state comes to offer an answer to the Enlightenment search for happiness. Its idealization is also an element in the rising cult sentimental, moral, social and political of the family. In all these matters we are dealing both with changes in 'real' social practices and with imaginary representations propagandist or wishful which may go against reality.

Individual self-awareness seems to derive less from classical antiquity than from the Judeo-Christian tradition. The emergence of the idea of natural goodness, earlier in the eighteenth century, curiously coincides with the rise of first-person fiction.

The earliest first-person narrative genre is the picaresque. In its authentic Spanish form (sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), the picaro's account of humankind and of himself is profoundly bleak. Bleaker still, and more explicitly Christian, is Grimmelshausen's German masterpiece Simplicius Simplicissimus (1669), which nevertheless assigns innocence to its first-person narrator. The French fictional mode ( Francion, Le Page disgraci) is aristocratic, disabused yet drawn to childhood, romance and fantasy. The non-fictional origins of modern autobiography include the journals of spiritual self-examination principally Puritan in English and Pietist in German. Protestant individualism takes literary form notably around 1720 in Defoe's down-to-earth fictional autobiographies ( Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, Roxana). French pseudo-memoirs reach their literary apogee in the 1730S. Though also authored mainly by the middle class (Prvost, Marivaux, Crbillon, Duelos), their protagonists are mainly aristocratic. But all these fictional memorialists are self-analytical. They exhibit both anxiety and considerable self-complaisance. To look ahead, the contradictory imperatives will appear most strikingly at the start of the most 'inward' of all writings, Rousseau's Rveries:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin»

Look at similar books to Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Regressive fictions: Graffigny, Rousseau, Bernardin and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.