Tim Cahill is the working-class Paul Theroux. He delights in finding stories too peculiar to be labeled merely off-beat.

Cahill writes in an agreeably off-the-wall fashion; he has a way with anecdotes, and he can be quite funny.

Cahill [has] the what-the-hell adventuresomeness of a T. E. Lawrence and the humor of a P. J. O Rourke.

Tim Cahill is one of those rare types whose fun quotient seems to increase in direct proportion to the diceyness of the situation.

You might call him crazy. You might call him reckless. But youll definitely call him hilarious. Adventure-travel crash-dummy Tim Cahill is to travel writing what P. J. ORourke is to political commentary.

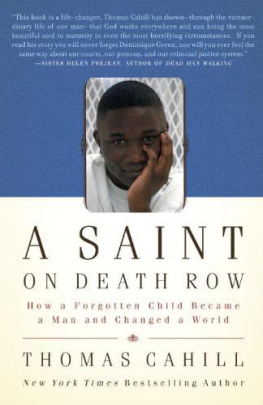

Books by Tim Cahill

Buried Dreams

Jaguars Ripped My Flesh

A Wolverine Is Eating My Leg

Road Fever

Pecked to Death by Ducks

Tim Cahill

Jaguars Ripped My FleshTim Cahill is the author of five books. He lives in Montana and is currently Outside magazines editor-at-large and a contributing editor to Esquire and Rolling Stone.

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, APRIL 1996

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, APRIL 1996

Copyright 1987 by Tim Cahill

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Bantam Books, Inc., New York, in 1987.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cahill, Tim.

Jaguars ripped my flesh / Tim Cahill.

p. cm. (Vintage departures)

eISBN: 978-0-307-77839-0

1. Adventure stories, American.

2. Travelers writings, American. 3. Voyages and travels. I. Title.

PS3553.A365J3 1996

813.54dc20

95-46721

Author photograph Marion Ettlinger

v3.1

To Richard J. and Elizabeth Cahill:

the first lucky thing that ever happened to me.

Acknowledgments

All stories originally appeared in Outside magazine except: The Lost World, Gorilla Tactics, and Eruption, which appeared in GEO; Shark Dive, which appeared in the Los Angeles Times Magazine; Fear of Falling, which appeared in West; and The Underwater Zombie, which appeared in Sport Diver.

Contents

Introduction

W hen I was growing up in the late 1950s and early 60s, there was very little in the way of literate adventure writing. Periodicals that catered to our adolescent dreams of travel and adventure clearly held us in contempt. Feature articles in magazines that might be called Mans Testicle carried illustrations of tough, unshaven guys dragging terrified women in artfully torn blouses through jungles, caves, or submarine corridors; through hordes of menacing bikers, lions, and hippopotami. The stories bore the same relation to the truth that professional wrestling bears to sport, which is to say, they were larger-than-life contrivances of an artfully absurd nature aimed, it seemed, at lonely bachelor lip-readers, drinkers of cheap beer, violence-prone psychotics, and semiliterate Walter Mitty types whose vision of true love involved the rescue of some distressed damsel about to be ravaged by bikers, lions, or hippopotami.

I was reminded, quite viscerally, of genre a few years ago while scuba diving on the barrier reef near Whitsunday Island just off the coast of Far North Queensland in Australia. Hookers Reef was a typical coral atoll, an ovoid shape from the air, the ring of reef almost completely exposed during low tide. Inside the wall was a shallow lagoon populated by crabs, shellfish, squid, remoras, and the odd marine turtle. Larger, more predatory organisms lived outside the reef, where the wall sloped down into a disconcerting darkness. I like diving big wallsthe sensation, gliding over the purple darkness of abysmal depths, is that of dream flightso I was diving outside the lagoon, in the realm of the predators.

The living reef had been trying to grow out from the wall, and it was building fastest near the surface, where there is the most light. This process had created some impressive overhangs: great expanses of golden brown antlerlike elkhorn coral stretched out perpendicular to the vertical wall twenty feet and more. In places these cantilevered coral platforms had collapsed, forming vast rubble heaps on the sloping wall below. There, spikes of elkhorn lay white, bleached in death, so that these amalgamated colonial organisms looked like the tangled bones of thousands of small children.

My diving partner was a New Zealand man who liked to be called The Kiwi. Together we had figured out the current, and were letting it carry us under the coral platforms and against the kaleidoscope of color that was the reef wall. At forty feet, there were tube sponges growing on yellow ledges like impossible purple cacti; we saw pink plating corals in the shapes of miniature pagodas; there were banks of fire coral and stands of soft corals: lacy blue-green sea fans and velvety golden sea whips that bent with the current so that in places the wall looked like some sloping meadow alive with alien wildflowers. Swimming against this mosaic of color was a teeming chaos of small, brightly colored aquarium fish that divers call scenicsblue-green wrasse; red parrot fish; bright yellow long-nosed butterfly fish; and several solitary Moorish idols, an aloof black-and-white fish of immense dignity designed, apparently, by a creator entirely fascinated with the art deco style.

When we hit the largest of the rubble slopes, there was no life at all.

It was about seven in the morning and the sun was still low in the sky. It slanted through the water in rippling, purely religious shafts, through which planktonic matter glittered and shifted like dust motes in the light from an attic window. The rubble slope was ash gray in color, and the entire effect, in contrast to the palette of the living wall, was one of devastation: the white broken branches of skeletal elkhorn coral, the sandy rubble, the smoky light. It looked like the aftermath of some hideous saturation bombing raid, the fires still smoldering. The eerie sense of dread was intensified by the total lack of fish on a reef that was otherwise a celebration of marine life.

This was ominous: there had been fish enough on the other rubble slopes. The Kiwi and I anxiously scanned the water ahead. We saw them below at about eighty feet: three sleek tiger sharks, on the feed.

They were forty feet away and the current was going to drive us directly over them. Tiger sharks are nasty fellowscertified man-eatersthe Australian divers refer to them as munchies; harmless lagoon-dwelling sharks such as black tips and white tips are called reefies. We drifted over this trio of munchies, and one rose, languidly, to greet us. He looked to be about seven or eight feet long.

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, APRIL 1996

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, APRIL 1996