PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

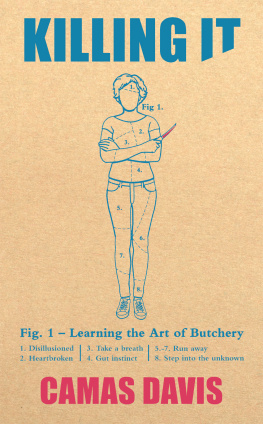

Copyright 2018 by Camas Davis

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Portions of this book, some in different form, appeared as part of Girl with Knife in Double Bind: Women on Ambition, edited by Robin Romm (Liveright, 2017), Human Principles in Ecotone, and Know Where Your Food Is From in MIX Magazine. Run Rabbit. No, Really, Run! a feature in an episode of This American Life was adapted from The Messy Middle, which appeared in Oregon Humanities.

LIBRARY OF CON GRESS CATALOGING-IN- PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Davis, Camas, author.

Title: Killing it : an education / Camas Davis.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018006205 (print) | LCCN 2018017105 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101980088 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101980071 (hardcover) |

Subjects: LCSH: Davis, CamasTravel. | Butchers (Persons)United StatesBiography. | Food writersUnited StatesBiography. | Slaughtering and slaughter-housesFrance. | Slaughtering and slaughter-housesOregonPortland.

Classification: LCC TS1959.5.D38 (ebook) | LCC TS1959.5.D38 A3 2018 (print) | DDC 664/.9029dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018006205

Some names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Version_1

FOR DJUNA,

AT THE VERY BEGINNING

OF ALL THIS

You road I enter upon and look around, I believe you are not all that is here,

I believe that much unseen is also here.

WALT WHITMAN , Song of the Open Road

Despite our machinations, we are ultimately unsuccessful at avoiding pain, loss and death. For animals, plants, and humans alike, there is more to life than not dying.

CHARLES EISENSTEIN, The Ethics of Eating Meat

Life, as the Russian proverb says, is not a walk across an open field. Experience is indivisible and continuous, at least within a single lifetime and perhaps over many lifetimes. I never have the impression that my experience is entirely my own, and it often seems to me that it preceded me. In any case experience folds upon itself, refers backwards and forwards to itself through the referents of hope and fear; and, by the use of metaphor, which is at the origin of language, it is continually comparing like with unlike, what is small with what is large, what is near with what is distant. And so the act of approaching a given moment of experience involves both scrutiny (closeness) and the capacity to connect (distance).

JOHN BERGER, Pig Earth

ONE

She was big. I didnt even know pigs could get that big. And although I could see for myself the astounding girth of her, I had no way of wrapping my head around the sheer physical reality of such a weight, until the mechanical hand that had lifted the dead old sow up out of the concrete bath of scalding water accidentally dropped her, from five feet high, onto the hard, cold concrete floor. It wasnt a thud, exactly. It was more of a ripple. A reverberating ripple of fat and skin and bone. Her heart was still in there, too, though no longer beating. So were her kidneys, her spleen, her lungs, her gallbladder, her small and large intestines, and everything else that had once made her alive but now made her a very heavy carcass on the floor. Without flinching, several men in dark-blue coveralls scrambled over to her body and attempted to push her back into the mechanical hand. As if this were actually possible. It most certainly was not.

Shes three hundred kilos. Too big, Marc Chapolard, who, along with his three brothers, had agreed to mentor me in the French ways of knife and bone, told Kate, my American translator and host, who told me. I did the math. Almost seven hundred pounds.

Just minutes before this pig carcass had accidentally fallen to the floor, a tall, thin, older gentleman, also in coveralls, had escorted the live sow through a wooden chute. As I watched her slowly make her wayshe had so much body to moveMarc explained that she was done having babies and was going to be turned into sausage.

Another man then secured what looked like a set of headphones onto the sows head.

Are they going to play her music? I asked, in all seriousness. No one answered me.

Then, with the meaty part of his palm, the man pressed a big red button on the wall, which sent a quick electrical current coursing through the headphones and into the skin and the subcutaneous fat and the bone and then the brain of the seven-hundred-pound mama, who dropped to the floor and began convulsing.

This felt to me like a private moment that I shouldnt be allowed to witness, these last shudders of life, this battle waged by her bodys nervous system, but I did not turn away. I was here to learn, after all. I was here to do something hard and real. I wasnt interested in wasting any more time pretending that what was unfolding in front of me wasnt really happening. Id spent the past ten years of my life doing that, and I was determined never to go down that road again. But words like hard and easy didnt seem to apply here. To the people working in this abattoir, to my French mentors raising pigs and butchering them back at the farm, this scenewould they even call it a scene?was, quite simply, work. Life, death, work. So I kept watching.

That makes her senseless to pain, Marc told Kate, who told me. This was the most humane way to kill a pig, he said. Sever all communication between the brain and the nervous system as quickly and painlessly as possible.

Shes not dead yet? I asked.

No, Marc told Kate, who told me. Shes unconscious. She wont be dead until they bleed her.

When I looked back, another man had hoisted the pig up by way of a chain wrapped around her back leg. He stuck a long knife into the space between the sows throat and where I imagined her heart to be.

She cant feel this, Marc said in French, Kate translating. If we didnt stun her first, she would feel it.

A woman held a plastic container underneath the sow to collect the blood. We all watched in silence as she rhythmically stirred the blood to keep it from coagulating. Time slowed to that rhythm. My brain slowed to that rhythm. My breath slowed to that rhythm. It was nowhere near a lullaby, but something in this womans focus, in her unwavering attention to this one small detail, something in the stillness of her face, almost soothed me. Almost.

But as I looked from the womans face to the sows now lifeless visage, I flashed upon an utterly inappropriate metaphor, one that linked the dead seven-hundred-pound sow to the very much alive one-hundred-thirty-pound me. This sow, I thought, had spent her entire adult life doing her job well. Her job was to make babies. Lots of them. Babies that could then be turned into food for our tables. And then, one day, someone had deemed her no longer useful. And just like that, her job had ended. Hence the headphones and the electric shock and the blood. At least she could still be used for sausage.