The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the United States government.

Copyright 2017 by Daniel P. Bolger

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

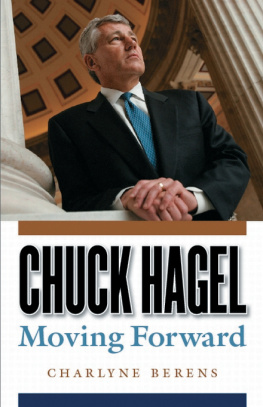

I knew Chuck and Tom Hagel long before I met them. In the terrible year of 1968 , young men like them lived in my suburban neighborhood west of Chicago. When their time came to serve, they went. Wed look for their faces when the camera scanned the crowd on the USO Bob Hope Christmas Special on television. Their fathers, like mine, fought in World War II or Korea. Their mothers showed us snapshots of bright-green jungles, thin foreign people in black pajamas, and loose-limbed young men in faded fatigues, smiling into the camera, Schlitz beer cans in hand. When they came home, they didnt talk about it. They took jobs or went to college. They moved on. I never heard of PTSD. And I never met a draft dodger.

You could make a powerful case, and many have, that the four most formative eras in American history were the Revolution and founding, slavery and the Civil War, the Great Depression and World War II, and the sixties and Vietnam. Of those, the last is surely the most discussed and least well understood. Were probably too close to it to sort it out completely.

Still, I think I owe it to Chuck and Tom, and to all the Vietnam veterans, most notably the officers and sergeants who led me when I joined the U.S. Army in the 1970 s, to try to figure out what the hell we did to our enemies and ourselves in Vietnam and at home. This book is my attempt, through the story of Chuck and Tom Hagel, to explain the lasting significance of the tumultuous events of the Vietnam War and 1960 s America. Ive worked hard to get it right. Wartime sergeants, like the Hagels and my own father, measure officer types by one hard standard: Do they know the real deal? I think I do. The Hagels certainly do.

Fifty years after Tet, Vietnam remains very much with us. I believe that many Americans, especially younger ones, do not realize the full import of this divisive war abroad and the contentious era at home, in particular the decisive events of 1968 . We continue to repeat the same errors and miss the same opportunities. I know. I lived through just those bloody mistakes in Iraq and Afghanistan. We see our past, but we dont understand it, even when men like Chuck and Tom Hagel plead with us to do so. Its past time to come to terms with Vietnam and the sixties. Thats why I wrote Our Year of War.

Daniel P. Bolger

Lieutenant General

U.S. Army, Retired

A year ago, none of us could see victory. There wasnt a prayer. Now we can see it clearly like light at the end of a tunnel.

GENERAL HENRI EUGNE NAVARRE

September 28, 1953

T om Hagel hated walking point. He disliked going first, breaking bush, knocking aside wet branches, stepping over fallen logs, slipping around leaning, mossy tree trunks, and all the while watching, listening, feeling, smelling, even tasting, seeking an enemy who knew exactly how to blend into the rotting woodwork. The Vietnamese jungle was greener than green, a riotous, enveloping ocean of foliage, the ground layer thick and tangled from the brown loam floor to a swaying mat of vegetation twice as high as Toms angular, spare six-foot frame. It made for tough slogging. And that was before somebody took a shot at you.

Toms head turned like a gun turret, slow and steady, listening and looking. He reached out, the long fingers on his left hand weaving through leaves and stems, just enough to push aside the abundant greenery. His right hand gripped the trigger region of his black M rifle. Eyes, ears, nose, and fingertips sought anything that did not belong there. An oddly broken branch. A Kalashnikov automatic rifle clicking from safe to fire. The sharp tang of human urine. A gleaming trip wire stretched like a garrote. Hagel had to stay alert for all of those telltale signs and dozens more. He had to do it despite the oppressive heat, the cloying humidity, and the pervading gloom. Not much sunshine filtered down through the soaring, thick tree canopy high above. In the fetid, tangled morass that choked the bottom of this rain forest, it was always dusk. Out there in the dim unending sea of vegetation, beyond sensing, lurked dangers past counting. Tom Hagel knew it only too well. There be monsters.

Yes, Tom Hagel hated walking point. But he was good at it. Nohe was great at it. He kept his rifle company alive. He made sure they won their fights, because those sharp clashes usually started with him. Woe to the thing that did not belong. With one squeeze of his M s trigger, Hagel would level it: rock and roll, full auto, punching out an entire magazine of twenty hot bullets as fast you could snap your fingers. And that would usually do it. The old sergeants, the ones who carried out this brutal business and lived to tell of it, said that he who shot first and in force gained the edge in a murderous jungle ambush. Tom Hagel was all about that edge.

Yet Tom Hagel hated doing it. He detested the war with all his heart. It wasnt just the dull ache of all combat soldiers in all wars, heartily sick of losing their friends, shaken by taking lives of strangers better left alone, and bone-tired from endless draining hours of hunting and being hunted. Tom Hagels disgust went beyond that. He considered the Vietnam War an abomination, an awful deviant strain far removed from Americas best instincts, a pointless bloody scrum on behalf of an utterly corrupt local ally. It was wrong, he said later, with characteristic bluntness. Still Tom Hagel walked point, and did it well.

He did it not for the flag, nor for the cause, such as it was, but for the other American soldiers who counted on him. It fell to this nineteen-year-old to balance the urgent pressure from his captain to move steadily onward and his own hard-earned wisdom to take care with each step. Slow is smooth and smooth is fast. That paradoxical phrase made no sense except to a battle-wary rifleman. Tom Hagel was one. The lives he saved would include his own, as well as those of his mates.