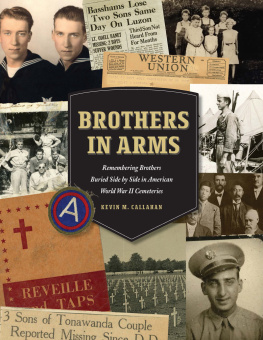

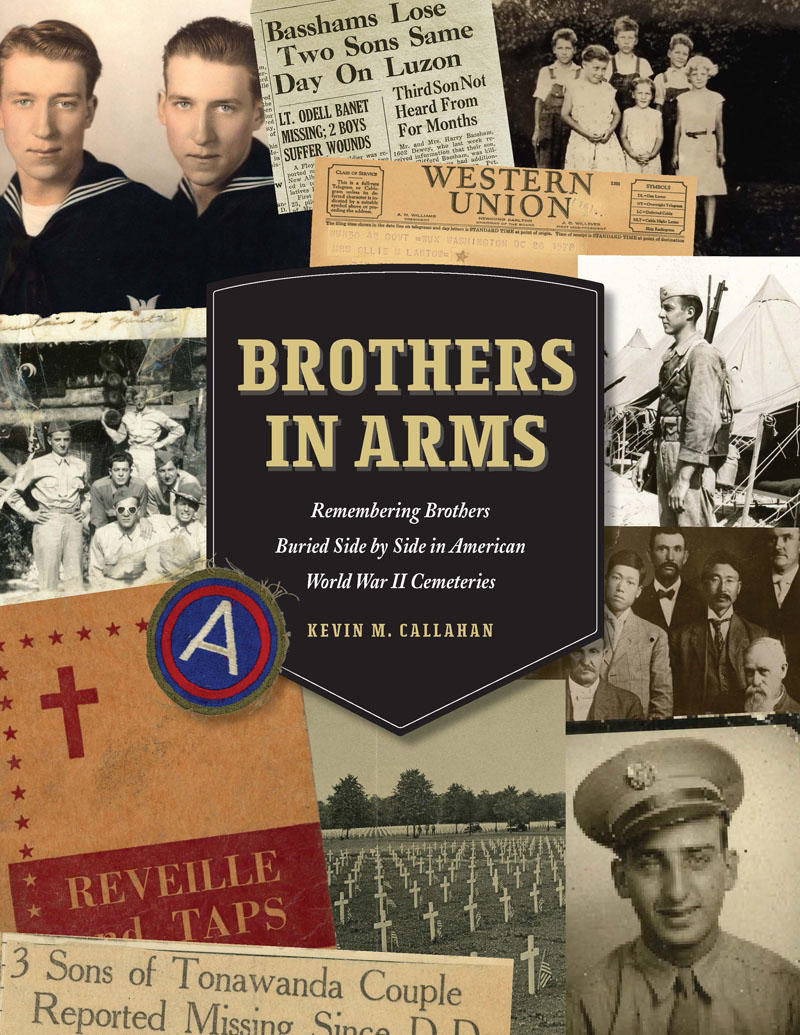

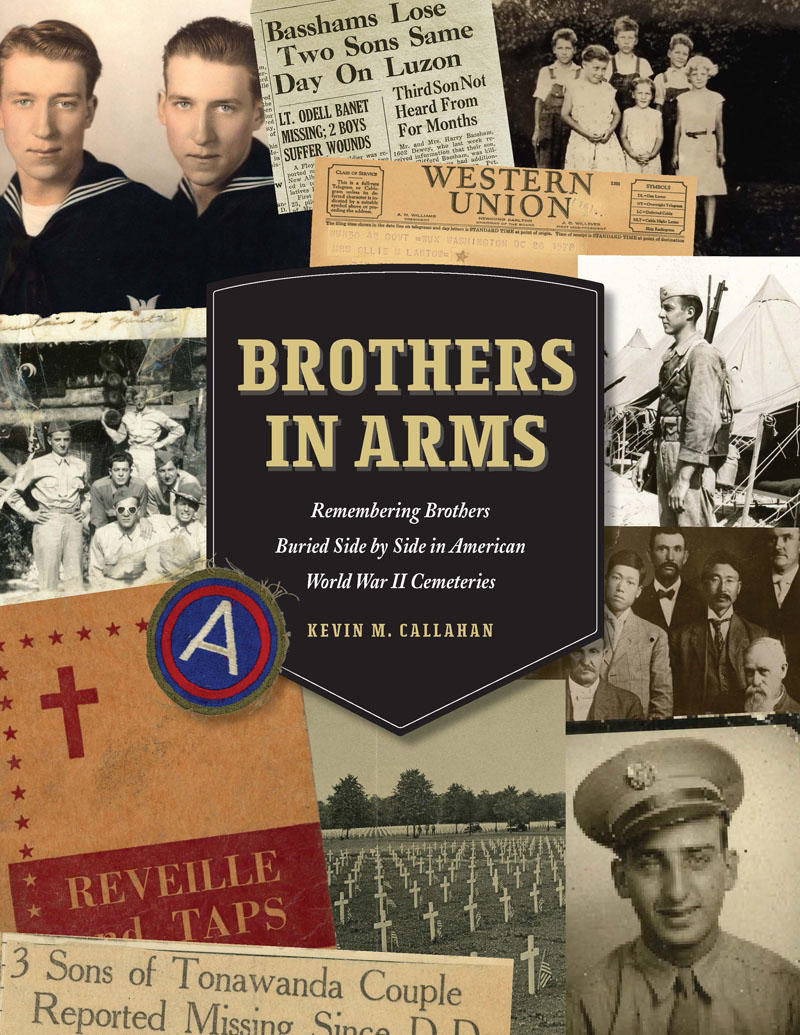

Brothers in Arms Press LLC

Rowayton, CT 06853

Copyright 2020 by Kevin M. Callahan and Brothers in Arms Press LLC

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever

First Brothers in Arms hardcover edition May 2020

Brothers in Arms logo and design are registered trademarks of Brothers in Arms Press LLC, the publisher of this work

For information about reprints, special discounts, bulk purchases, or speaking engagements, please contact Kevin M. Callahan at

Design by Jeryy Takigawa, Takigawa Design with Jay Galster

Cemetery photos by Katherine Lin, unless otherwise noted

Printed in Wisconsin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available

ISBN 978-0-578-46885-3

www.brothersinarmsbook.com

Dedicated to U.S. Army Captain

Eric George Lundstedt (1969-2018)

who was with me on that first trip to Normandy,

and to all those who have served

Table of Contents

Introduction

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

L incolns Gettysburg Addresswhat historian Garry Wills called the words that remade Americatook place at the dedication of a military cemetery. The president and other leading dignitaries gathered on a brisk November afternoon in 1863 to dedicate the Soldiers National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, four and half months after the decisive battle.

At the time, the idea of a national cemetery was a relatively new concept in the United States. Soldiers killed in the American Revolution or the War of 1812, for example, were generally retrieved from the battlefield, returned home, and buried in family or church plots. The first military cemetery created and sponsored by the U.S. government was established in Mexico City in 1851 to hold the remains of 750 war dead from the Mexican-American War. It was the first American military cemetery placed in a foreign country. It would not be the last.

The scale of military deaths in the Civil Warmore than 600,000impelled the U.S. government to take a more active role in retrieving, identifying, and burying fallen soldiers. In July 1862, Congress created the U.S. National Cemetery System and by the end of that year, fourteen national cemeteries were established including Arlington National. The cemetery at Gettysburg was therefore not the first national cemetery, but it was different from the others in one important respect: how it represented the individual soldier. As Drew Gilpin Faust wrote in her Pulitzer-Prize nominated book, This Republic of Suffering: The cemetery at Gettysburg was arranged so that every grave was of equal importance; William Saunderss design, like Lincolns speech, affirmed that every dead soldier mattered equally regardless of rank or station.

This tradition of burying all American war dead regardless of rank or station would continue in American overseas cemeteries established after World War I and World War II.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

World War I presented a new challenge for U.S. military and government officials: what to do with more than 100,000 Americans who died overseasbring them home or bury them near the battlefields where they fell? Ultimately, the government let the families of the fallen decide whether to have the remains repatriated to their homes or buried at one of eight newly-established permanent cemeteries in Europe. Roughly 60 percent chose repatriation, while 40 percent chose overseas burial. To construct and administer these new cemeteries, Congress created the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) in 1923. General John J. Pershing, hero of World War I, was named as its first chairman. These eight World War I cemeteries contain over 30,000 burials and list nearly 4,500 names on the Walls of the Missing.

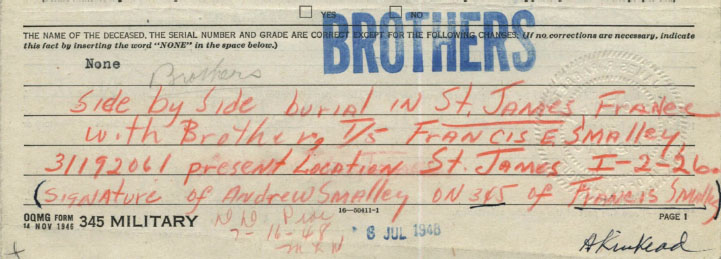

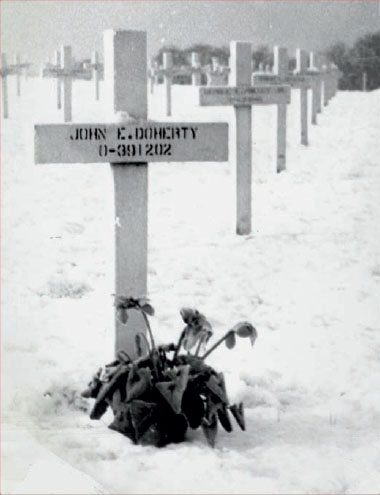

The disposition of war dead in World War I would serve as a model for World War II, when more than 400,000 Americans died in a conflict that stretched across the globe. Due to the grisly but heroic work of the U.S. Armys Graves Registration Service (GRS), many fallen Americans had been retrieved, identified, and buried in hundreds of temporary cemeteries around the world. Again, the government let families decide what to do with the remains, and once more, about 60 percent chose repatriation, 40 percent chose overseas burial. To hold these foreign burials, the ABMC established fourteen permanent American cemeteries overseas. In 1949, General George C. Marshall, the Organizer of Victory, took over as chairman of the ABMC when Pershing died. Working in concert with the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, they hired some of the finest architects, landscape architects, and artists to design these new cemeteries and memorials. As in World War I, no cemeteries would be placed on enemy soil. Therefore, there would be no burial grounds in Germany or Japan. Instead, those fourteen cemeteries were placed in eight countries: five in France, two in Belgium, two in Italy, and one each in: the Netherlands, England, Luxembourg, Tunisia, and the Philippines. These grounds hold over 90,000 burials and list nearly 80,000 names on the Walls of the Missing.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate we can not consecrate we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

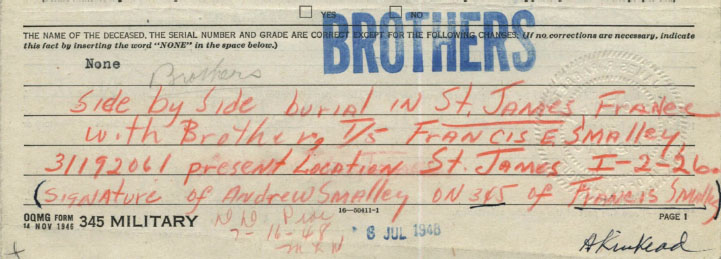

The goal of this book is simple: to tell the stories, in words and images, of brothers buried side by side in American World War II cemeteries overseas.

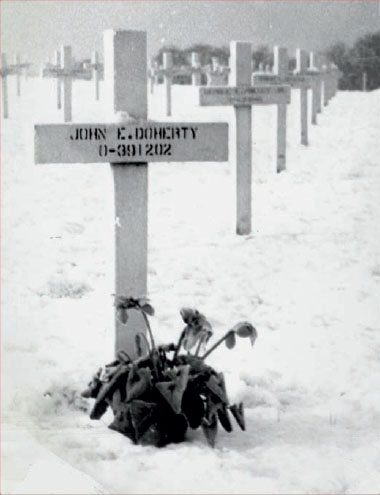

I visited my first American cemetery at Normandy about twenty-five years ago while backpacking through Europe. I was struck by it. There, I took a photo of the gravesite of Sergeant Frank McNally from New York. I realized he was likely about my age at the time he died, and that it was due to the sacrifice of people like him that I was able to trek through a free and prosperous Europe some fifty years later. That photo has hung on my wall ever since.

Next page