Other books

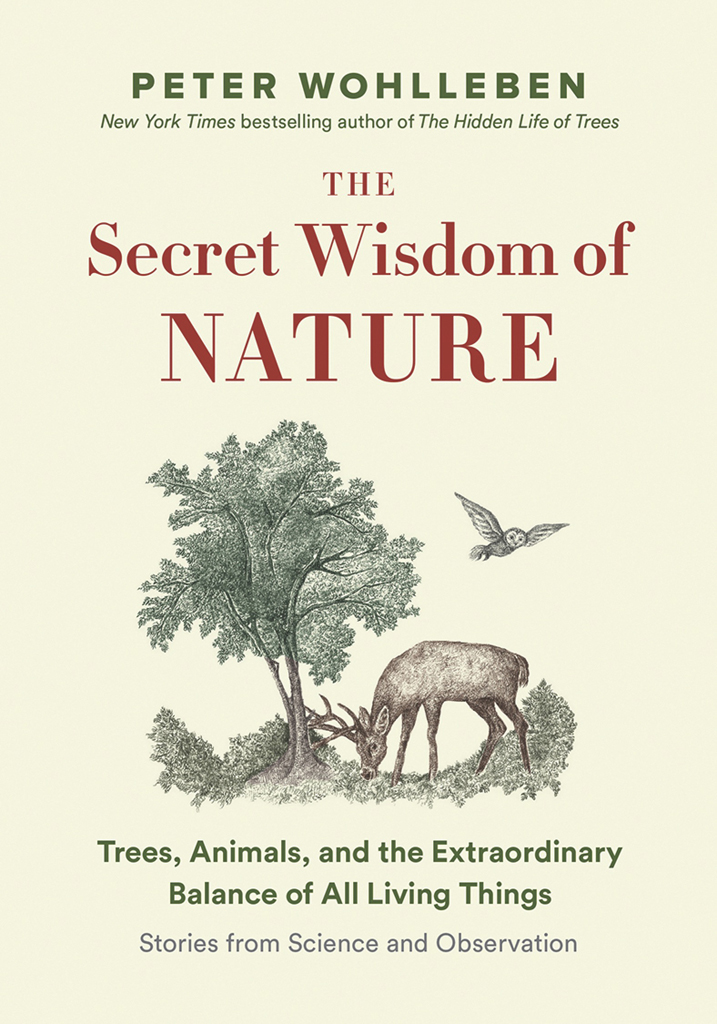

by Peter Wohlleben

The Hidden Life of Trees:

What They Feel, How They Communicate

Discoveries from a Secret World

The Inner Life of Animals:

Love, Grief, and CompassionSurprising

Observations of a Hidden World

The Hidden Life of Trees:

The Illustrated Edition

PETER WOHLLEBEN

translation by JANE BILLINGHURST

Copyright 2017 by Ludwig Verlag, Munich, part of the Random House

GmbH publishing group

Originally published in Germany in 2017 as Das Geheime Netzwerk der Natur

English translation copyright 2019 by Jane Billinghurst

First published in English by Greystone Books in 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books Ltd.

www.greystonebooks.com

David Suzuki Institute

www.davidsuzukiinstitute.org

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77164-388-7 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-77164-389-4 (epub)

Copyediting by Shirarose Wilensky

Jacket and interior design by Nayeli Jimenez

Jacket illustration by Briana Garelli

Greystone Books gratefully acknowledges the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples on whose land our office is located.

Greystone Books thanks the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada for supporting our publishing activities.

Contents

Introduction

N ATURE IS LIKE the mechanism in an enormous clock. Everything is neatly arranged and interconnected. Every entity has its place and its function. Take the wolf, for example. Under the order Carnivora, there is the suborder Caniformia, which includes the family Canidae and the subfamily Caninae, which includes the genus Canis, and within that genus is the species wolf. Phew. As predators, wolves regulate the number of plant eaters so that deer populations, for example, do not multiply too rapidly. All animals and plants are held in a delicate balance, and every entity has its purpose and role in its ecosystem. This way of organizing life supposedly gives us a clear view of the world, and thus a sense of security. As erstwhile plains dwellers, our most important sense is sight, and our species relies on viewing things clearly. But do we really have a clear view of what is going on?

The wolves remind me of a story from my childhood. I was about five years old and on vacation visiting my grandparents in Wrzburg when my grandfather gave me an old clock. The first thing I did was take the clock apart, because I just couldnt wait to find out how it worked. Even though I was convinced that I knew how to put it back together in working order, I couldnt do it. After all, I was just a young child. After I rebuilt it, there were a few cogs left overand a grandfather who was not in the best of moods. In the wild, wolves play the role of such cogs. If we eradicate them, not only do the enemies of sheep and cattle ranchers disappear, but the finely tuned mechanism of nature also begins to run differently, so differently that rivers change course and many local bird species die out.

Things can also go awry when a species is added; for example, when the introduction of a nonnative fish leads to a massive reduction in the local elk population. Because of a fish? The earths ecosystems, it seems, are a bit too complex for us to compartmentalize them and draw up simple rules of cause and effect. Even conservation measures can have unexpected results. Who knew, for example, that recovering crane populations in Europe would affect the production of Iberian ham?

And so its high time we took a good look at the interconnections between species both large and small. And if we do that, we get a chance to contemplate odd creatures, such as nocturnal red-headed flies that take wing only in winter on the lookout for old bones, or beetles that seek out cavities in rotting trees, where they dine on the feathery remains of pigeons and owls (but only when theyre mixed together). The more light you shed on relationships between species, the more fascinating facts you reveal.

But nature is much more complex than a clock, isnt it? In nature, not only does one cog connect with another; everything is also connected by a network so intricate that we will probably never grasp it in its entirety. And that is a good thing, because it means that plants and animals will always amaze us. Its important for us to realize that even small interventions can have huge consequences, and wed do better to keep our hands off everything in nature that we do not absolutely have to touch.

So you can get a clearer picture of this intricate network, Id like to show you some examples. Lets be amazed together.

Of Wolves, Bears, and Fish

W OLVES ARE A wonderful example of how complex connections in nature can be. Amazingly enough, these predators are able to reshape riverbanks and change the course of rivers.

The matter of changing the course of rivers happened in Yellowstone, the very first national park in the United States. In the nineteenth century, people began the process of eradicating wolves in the park, primarily in response to pressure from ranchers in the surrounding area, who were worried about their grazing livestock. The last pack was wiped out in 1926. Individual wolves continued to be spotted occasionally until the 1930s, when they, too, were eliminated. Other animals living in the park were either spared or, in some cases, actively encouraged. In harsh winters, for example, rangers went so far as to feed the elk.

Changes came quickly. No sooner was pressure from predators lifted than elk populations began to increase steadily, and large areas of the park were stripped bare. Riverbanks were particularly hard hit. The juicy grass at the rivers edge disappeared, along with all the saplings growing there. The desolate landscape didnt even provide enough food for birds, and the number of species drastically declined. Beavers joined the ranks of the losers, because beavers depend not only on water but also on the trees that grow close by. Willows and poplars are some of their favorite foods. They cut them down so that they can reach the trees nutrient-rich new growth, which they then devour with great relish. Because all the young deciduous trees along the waters edge were ending up in the stomachs of hungry elk, the beavers had nothing to gnaw onand they disappeared.

Riverbanks became wastelands, and because there was no longer any vegetation to protect the ground, seasonal flooding washed away ever-increasing quantities of soiland erosion advanced rapidly. As a result, the rivers began to meander more and follow increasingly winding routes through the landscape. The less protection there is for the underlying layers of soil, the stronger the serpentine effect, especially on flat ground.