PREFACE

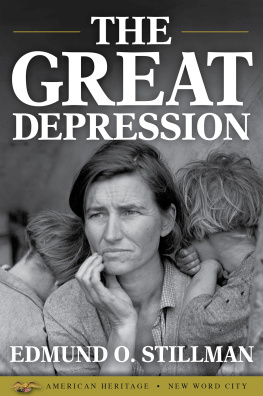

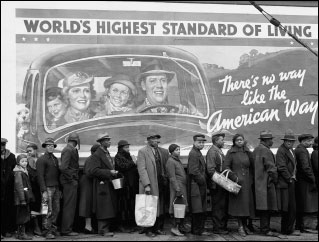

As I COMPLETED THIS BOOK, the United States was entering its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression of 1929 to 1941. References to the 1930s blanketed the airwaves, the newspapers, and the online blogs, as well as the press conferences of politicians, the testimony of federal regulators, and the oracular pronouncements of economists. Because of structural reforms enacted then and bolstered by subsequent administrations, this was never supposed to happen again. But even before our latest economic crisis, the painful conditions of Depression years continued to haunt us: as distant memories fading into myth, as a stern warning that tough times might return, and, finally, as a blow to Americas sense of itself as a land of endlessly open possibilities. Every postwar recession, every economic crisis, inevitably triggered fears going back to the 1930s.

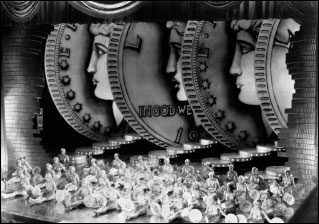

Surprisingly, the Depression was also the scene of a great cultural spectacle against the unlikely backdrop of economic misery. The crisis kindled Americas social imagination, firing enormous interest in how ordinary people lived, how they suffered, interacted, took pleasure in one another, and endured. It might seem unusual to approach those calamitous years through their reflection in the arts, but the art and reportage that helped people cope with hard times still speak to us today: strangely beautiful photographs documenting the toll of human suffering; novels that respond to the social crisis, sometimes directly, often obliquely; romantic screen comedies whose wit and brio have never been surpassed; dance films that remain the ultimate in elegance and sophisticated grace; jazz-inflected popular music that may be the best America has ever produced. Combining the truth of art with the immediate impact of entertainment, these works give us intimate glimpses of the inner history of the Great Depression, including its plaintive longing for something better, that place at the end of the Yellow Brick Road. They provide us with singular keys to its moral and emotional life, its dream life, its unguarded feelings about the world.

The thirties were also the testing ground for political debates that continue to this day: about totalitarianism and democracy, about the relations between social welfare, individual initiative, and public responsibility, about the ideologies of the twentieth century. Along with other leading intellectuals, some of my best teachers received their baptism of fire in those debates, and I undoubtedly soaked up some of this influence. But this book is not about thirties intellectuals and their ideas, which historians and critics have covered extensively, but about the arts and society, the crucial role that culture can play in times of national trial. What first drew me to the period were the movies, still wonderfully watchable, although the techniques and the scale of film production have altered dramatically. Moviemaking then was dominated by individual studios, each with its distinct style: the punchy and topical films of Warner Brothers, ripped from the headlines of today the Frank Capra comedies, with their unique common touch, that put Columbia Pictures on the map; the European romantic sophistication that Ernest Lubitsch brought to Paramount; the stylish Germanic horror films made at Universal; the Astaire-Rogers films and romantic comedies that floated RKO.

Some of these films are visibly marked by the Depression, others seemingly not at all, at least until we look at them more closely. This book examines the rich array of cultural materialbooks, films, songs, pictures, designsto fathom the life and mind of the Depression. But it also brings history to bear on these peerless works to understand where they came fromto listen to their dialogue with their own times. Great art or performance helps us understand how people felt about their lives; it testifies to what they needed to keep going. This why we return again and again to classic American social novels, from Uncle Toms Cabin, The House of Mirth , and The Jungle , different as they are, to The Great Gatsby and The Grapes of Wrath . Each in its own way enables us to feel the pulse of society from the inside. Dancing in the Dark , then, shows how the arts responded to a society in upheaval and, at the same time, how they altered and influenced that society, providing a hard-pressed audience with pleasure, escape, illumination, and hope when they were most needed.

No two views of the 1930s are entirely the same. The critic Alfred Kazin, who saw the thirties as decisive for his own life, expressed one deeply felt view many years later. No one who grew up in the Depression ever recovered from it, he wrote in 1980. To anyone who grew up in a family where the father was usually looking for work, every image of the thirties is gray, embittered. in economic anxiety. Unfailingly generous to his family, a devoted union man, he remained thrifty, self-denying, pessimistic about the future, and very conservative about risk and change. Until his death, in 1992, he followed the stock market every day as a spectator sport but, always averse to risk, never invested a cent after pulling out in 1928.