FOR C. R. C LEVIDENCE

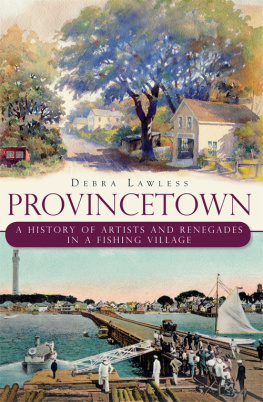

The Maytrees were young long ago. They lived on what still seems antiquitys very surface. It was the tip of Cape Cod, that exposed and mineral sandspit. The peninsula here was narrow between waters. Its average elevation was fifteen feet. It spiraled counterclockwise from the scarps of Truro and came rumpling over dunes to the harbor, Provincetown, inside the spiral. The town name of Provincetown was for a time Cape Cod. Generations before Jamestownlet alone PlymouthBritish fishermen loaded their holds with split cod.

No Wampanoag Nauset tribes, not even Pamets, settled on Provincetowns poor sand or scrub woods; they were farmers. At river mouths as far north as Truro, however, Nausets stayed, and built permanent villages more thickly than in most of New England, for clams and oysters abounded, and south of the Namskaket creeks they found soil for squash and corn.

The Maytrees lives, like the Nausets, played out before the backdrop of fixed stars. The way of the world could be slight, then and now, but rarely, among individuals, vicious. The slow heavens marked hours. They lived often outside. They drew every breath from a wad of air just then crossing from saltwater to saltwater. Their sandspit was a naked strand between two immensities, both given to special effects.

Toby Maytree grew up in Provincetown and spent most of his life there. His father was one of several guards stationed on the backside, on the cliffs by the Atlantic. Like some other coast guards, Maytrees father built for his family a rough shack on the bare sands near the coast guard station. Young Maytree and his mother camped out for summer weeks there in the one-room wood shack above the great ocean beach. They exchanged visits with the guards. Later, after the war, Maytree became a poet of the forties and fifties and sixties. He wrote four book-long poems and three books of lyrics.

His wife, Lou Maytree, rarely spoke. She painted a bit on canvas and linen now lost. They acted in only two small eventsthree, if love counts. Falling in love, like having a baby, rubs against the current of our lives: separation, loss, and death. That is the joy of them.

Twice a day behind their house the tide boarded the sand. Four times a year the seasons flopped over. Clams live like this, but without so much reading as the Maytrees.

They remembered the central post officethe post office where everyone met mornings and encouraged everyone else for the day and night ahead. They were young when passenger trains to Provincetown replaced freights. When he was eighteen, he joined crews all over the Cape to clear and rebuild after the big hurricane.

Toby Maytree wanted to engage the enemyeither onein gunfight. Instead he spent the war at the San Francisco Office of War Information. He wrote broadcasts for Pacific troops. By then, Lou was in college. Later, married, both Maytree and Lou liked the idea of seeing the world. Neither, however, was willing to sacrifice free time for a job.

Maytree picked up cash by moving houses for friends and whacking up additions, at whim. They voted. They were not social thinkers, but their friends were. Their summer friends, in particular, harvested facts row on row from newspapers like mice on corncobs. The Maytrees were not always up-to-the-minute. Their city friends envied their peace.

She owned their house. Her mother bought it when Lou was a girl. Her mother and Lou had moved to Provincetown from Marblehead, Massachusetts, after the man of the family, a lawyer, left one morning for work and never came back. No one knew that ordinary breakfast would be their last. Why not memorize everything, just in case?

For a long time they owned no car, no television when that came in, no insurance, no savings. Once a week they heard world news on the radio. They supported striking coal miners families with cash. They loved their son, Pete, their only child. Between them they read about three hundred books a year. He read for facts, she for transport. Nothing about them was rich except their days swollen with time.

Lou Maytrees height and stillness made her look like a statue. Her fair hair and her white skins purity contrasted with the red she wore year-round to cheer the scene. Her courtesy, her compliance, and especially her silence dated from a time otherwise gone. Her size, her wide eyes and high brow, and her upright carriage gave her an air of consequence. Intimacy came easily to her, but strangers could not see it.

When she was old, she lived alone in the Maytrees one-room shack in the parabolic sand dunes. She crossed the backshore dunes into the bayside town Fridays and stocked up. A straw hat kept her face clear. Year after year her eyes set farther back and their lavender lids thinned.

Throughout her life she was ironic and strict with her thoughts. She went dancing most Friday nights in town. People said that Maytree, or felicity, or solitude had driven her crazy. People said she had been an ugly girl, or a child movie star; that she inherited fabulous sums and lived in a shack without pipes or wires; that she read too much; that she was wanting in ambition and could have married anyone. She lacked a womans sense of doom. She did what she wantedlike who else on earth? All her life she found dignity over-rated. She rolled down dunes.

Most of the few and unremarkable things Lou and Toby Maytree did occurred in their old beachside house on the towns front street, and in fact in its bed.

Their beds frame was old pipe metal, ironstone. Lou Maytree painted its arched headboard and footboard white. Every few years she sanded its rust rosettes and painted it white again. This was about as useful as she got, though she stretched a dollar for food. One could divide their double bed into her side and his side by counting four pipes over, but the two ignored parity. He slept with a long leg flung over her, as a dog claims a stick.

Once while he slept on his side, his legs thrashed and he panted. She pressed his shoulder.

Chasing a rabbit?

He exhaled and said, tap-dancing.

I T BEGAN WHEN L OU Bigelow and Toby Maytree first met. He was back home in Provincetown after the war. Maytree first saw her on a bicycle. A red scarf, white shirt, skin clean as eggshell, wide eyes and mouth, shorts. She stopped and leaned on a leg to talk to someone on the street. She laughed, and her loveliness caught his breath. He thought he recognized her flexible figure. Because everyone shows up in Provincetown sooner or later, he had taken her at first for Ingrid Bergman until his friend Cornelius straightened him out.

He introduced himself. Youre Lou Bigelow, arent you? She nodded. They shook hands and hers felt hot under sand like a sugar doughnut. Under her high brows she eyed him straight on and straight across. She had gone to girls schools, he recalled later. Those girls looked straight at you. Her wide eyes, apertures opening, seemed preposterously to tell him, I and these my arms are for you. I know, he thought back at the stranger, this long-limbed girl. I know and I am right with you.

He felt himself blush and knew his freckles looked green. She was young and broad of mouth and eye and jaw, fresh, solid and airy, as if light rays worked her instead of muscles. Oh, how a poet is a sap; he knew it. He managed to hold his eyes on her. Her rich hair parted on the side; she was not necessarily beautiful, or yes she was, her skins luster. Her pupils were rifle bores shooting what? When he got home he could not find his place in Helen Keller.