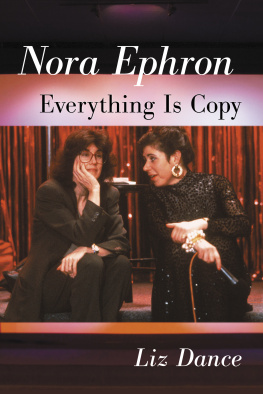

Nora Ephron has written a very clever play. A sophisticated evening of cheeky merriment.

An irreverent, stylish joyride, wickedly entertaining.

Scripted with razor-sharp wit. Takes cattiness soaring to transcendent heights.

A highly engaging vaudeville, part dual biography, part witty appreciation, part extended argument, part send-up and part rueful meditation on vanity, morality, the stories we tell and the lives we manufacture. Inspired. A form-breaker.

A sly and deftly poised entertainment. Artfully theatrical.

INTRODUCTION

On a January night in 1980, Lillian Hellman was in bed, watching The Dick Cavett Show, when Mary McCarthy hurled her famously vicious remark about Hellman into the ether. Are there any writers you think are overrated? Cavett asked. McCarthy replied: The only one I can think of is a holdover like Lillian Hellman, who I think is tremendously overrated, a bad writer, and dishonest writer, but she really belongs to the past. What is so dishonest about her? Cavett asked. Everything, McCarthy said. But I said once in some interview that every word she writes is a lie, including and and the.

That remark, and what followeda $2.25 million lawsuit Hellman filed against McCarthybrought to a head almost forty-five years of skirmishing between the two women. Some of it is easy to document because it was in print. Mary, writing in Partisan Review in 1946, attacked Lillians work. Lillian responded in a Paris Review interview in 1964. Mary struck again in a People magazine interview in 1979. And so forth. But where and exactly how the enmity began is maddeningly elusive. Did the two women meet for the first time at a dinner party in 1936? Perhaps. Did they argue at that dinner about the Spanish civil war and the incredibly brave civil war martyr Andres Nin? Mary McCarthy argued with someone at a dinner party about the Spanish civil war and Andres Nin, because she wrote a short story about a dinner party where a young woman remarkably like Mary McCarthy has an argument with someone about the Spanish civil war and Andres Nin. Was that someone Lillian Hellman? Or did McCarthy confuse Hellman with another Stalinist, named Leane Zugsmith?

Did their enmity begin not because of politics but for more personal reasons? Perhaps. For it seems that one night in 1936, while Mary McCarthy was living with Partisan Review editor Philip Rahv, Lillian Hellman met Rahv and attempted to seduce him. When he returned to the apartment he was sharing with McCarthy, he claimed he hadnt actually slept with Hellman because he didnt find her attractive. The incident, McCarthy told one of her biographers, was the only real fight of her relationship with Rahv. Was Rahv telling the truth? McCarthy believed him. Whether she was right to (do you?) is another mystery.

The two women clearly and absolutely met at Sarah Lawrence College in 1948, and they most definitely had a fight there. Was the fight about the incredibly brave Andres Nin, as McCarthy claimed? Did McCarthy spend her life picking fights about the incredibly brave Andres Nin? Did she confuse the fight shed had at the dinner party years earlier with the fight they had at Sarah Lawrence? Theres no way to know. Years later, when Marys biographers went to poet Stephen Spenderwho was supposedly therefor the details, he turned out to be entirely confused about the episode. He thought it had taken place at his home. It had actually taken place at the home of Harold Taylor, then president of Sarah Lawrenceand Spender hadnt been there at all. It seems, in fact, that there were not one but two fights that day: one at Taylors, and one later, at Spenders. Or were there?

I began thinking about writing something about Lillian Hellman and Mary McCarthy a few years ago, when I read two biographies of McCarthy, Writing Dangerously by Carol Bright-man, and Seeing Mary Plain by Frances Kiernan. Id never met McCarthy, but Id known Lillian Hellman. I met her when I was a journalist, and I have to say that for several years I was under her spell. Lillian was fun, a wonderful hostess, cook, correspondent, and storyteller. It was quite a while before I began to suspect that the fabulous stories she entertained her friends with were, to be polite about it, stories. When she sued McCarthy years afterward, I wasnt surprised. She was sick by then, and legally blind. And her angerthe anger that was her favorite accessoryhad turned wearisome, even to those who were loyal to her.

When I read the biographies of McCarthy, it crossed my mind that there might be something to write about McCarthy and Hellman and their collision. At first I thought of some sort of high-minded television seriessix or seven parts, saythat told the story of their parallel, albeit dissimilar, lives. Mary, of course, was an orphan, Catholic, abused. Lillian was an only child, Jewish, spoiled. Mary was beautiful. Lillian was not. Mary became an intellectual and a star in a world that had a pathological distrust not just of commercial success but also of stars. Lillian was the epitome of the commercial playwright, rich and famous. Mary was a Trotskyite, Lillian a Stalinist. (Lillian was whats known as an unreconstructed Stalinist. As she lay dying, someone I know said to her, Well, Lillian, what do you think of Joe Stalin now? She replied, You cant make an omelette without breaking eggs.) Perhaps most crucial, Mary was a critic, a great critic. Lillian was not a great playwright, but she was a great dramatist. It seemed so extraordinary that these two womenwhod written so much, whod led such rich and complicated lives, whod almost never been in the same room, who truly couldnt stand each otherhad ended up, in some terrible way, linked forever.

But every time I thought about this television seriesnow called something fabulously pretentious (in my imagination), like Two American WomenI became tired. The words Who can I get to write it? kept crossing my mind. The last thing I wanted to work on was a long project that would end up seeming like docudrama. And Id seen quite a lot of dramatizations of Lillians life, onstage and in film. Shed been played by Jane Fonda, Elaine Stritch, Linda Lavin, Zoe Caldwell, and Judy Davis. But none of it had really caught Lillian, the Lillian I knew, anyway; and all of it seemed so constricted, even by the loose rules of biography.