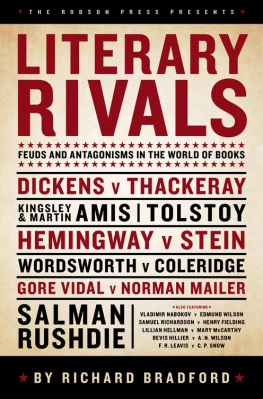

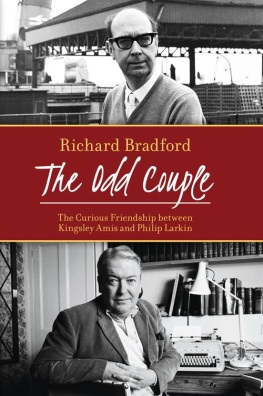

T HE CRITIC HAROLD Bloom is responsible for the most widely debated thesis on bitterness and antagonism in literature. In The Anxiety of Influence (1973) he argues that every writer enters a contest with a particular predecessor; the best of the newcomers will free themselves from anything resembling a debt to what has been done before, while everyone else will be inhibited by an endless struggle to do so. It is a tempting and intellectually demanding model of the tensions and impasses of writing, but it is weakened by something that its central premise ignores. In the real world, most writers are not looking back over their shoulders to their long-dead precursors; instead, they are concerned with the activities of their contemporaries, some of whom might be or have once been their closest friends.

Through lack of statistics, we remain ignorant as to whether writers outrank the rest of us as pathological hypocrites and egotists of Olympian proportion, but what is clear enough is that their success will aggravate envy among others in the same business. Sometimes individual enmities appear petty and laughable compared to the states of collective rage conjured against one author or book. In this respect, Rushdie, albeit involuntarily, proved that murderous religious fundamentalism had not expired with the Enlightenment. Although no fatwa was ever issued against J. C. Squire, by the 30s he too seemed to be the last man standing among those who had first dared to question the all-consuming benefits of modernism.

It has long been a maxim of highbrow criticism that literature should be allowed to float free from the untidy, often vulgar, circumstances of its making only then can its aesthetic qualities properly be appreciated.

I disagree.

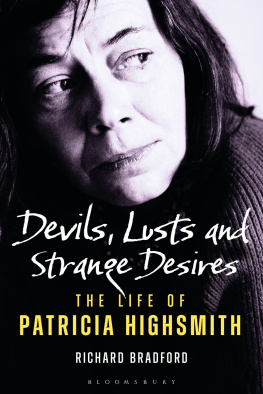

The stories that underpin the creation of books and poems are often as engrossing as the works themselves. A glimpse of what authors are really like ranging, as we will see, from the heroic to the contemptible brings new life to the words on the page. While Vladimir Nabokovs Lolita is one of the most notorious, brilliantly executed works of twentieth-century fiction, few of us would actually admit to deriving unreserved enjoyment from reading it. The question of what Nabokov hoped to achieve has taxed critics for decades. As I will show, it was, in part, inspired by sex and eroticism, but it also served as Nabokovs means to a private and cruelly calculated end: the novel was designed to humiliate a man he had grown to despise.

With Kubla Khan and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Coleridge licensed a special brand of self-indulgence and impenetrability and, in claiming to discern something similar in Shakespeares writing, secured acclaim for himself as a critic. In both respects, his achievements are in fact linked to his short career as a Peeping Tom. Wordsworth was not pleased, especially since the subject of Coleridges ogling was his own sister-in-law.

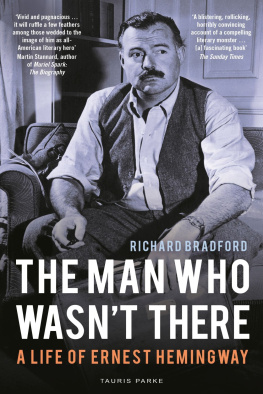

Hemingway the man epitomised the brave unsentimental manner of his fiction, a form of writing that won him the Nobel Prize, or so we are routinely led to believe. What biographers tend to leave undisclosed are the rather embarrassing aspects of his years in 20s Paris, where he alienated and insulted figures he had initially treated with unreserved sycophancy. Perhaps he was searching for a role in the new cultural presidium, albeit very clumsily, but one has to wonder if he believed that patronage would automatically confer talent: some of his early writings are extraordinarily dreadful.

For those of you disposed to an extended, leisurely tour of fraught relationships and encounters, the chapters whose title includes the letter v. (for versus) will suit you best, providing longer and more detailed accounts. The other, more succinct chapters will appeal to those with an interest in one-on-one encounters, covering some of the deep-rooted, and often distasteful, features of the literary world. Additionally, there are pages interspersed throughout the book with quotations by, or about, the writers, for even more rapid digestion. However, these are not intended as a form of relief quite the contrary. They disclose the often hateful spirit that has spawned some of the most fascinating and notorious bouts of literary loathing.

US BILE

Hemingway always willing to lend a helping hand to the one above him.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

What other culture could have produced someone like Hemingway and not seen the joke?

GORE VIDAL

I knew William Faulkner well. He was a great friend of mine. Well, as much as you could be a friend of his, unless you were a fourteen-year-old nymphet.

TRUMAN CAPOTE

I guess Gore left the country because he felt that he was underappreciated here. I have news for him: people who actually read his books will underappreciate him everywhere.

TRUMAN CAPOTE, ON GORE VIDAL

Hes a full-fledged housewife from Kansas with all the prejudices.

GORE VIDAL, ON TRUMAN CAPOTE

Vidals phrasings sometimes used to have a certain rotundity and extravagance, but now he had descended straight to the cheap, and even to the counterfeit. What business does this patrician have in the gutter markets, where paranoids jabber and the coinage is debased by every sort of vulgarity?

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

Thats not writing thats typing.

TRUMAN CAPOTE, ON JACK KEROUAC

A man must be a very great genius to make up for being such a loathsome human being.

MARTHA GELLHORN, ON ERNEST HEMINGWAY

I hated [Salingers Catcher in the Rye]. It took me days to go through it blushing with embarrassment for him every ridiculous sentence of the way. How can they let him do it?

ELIZABETH BISHOP

It was a good career move.

GORE VIDAL, UPON HEARING OF TRUMAN CAPOTES DEATH

BRITAIN

V.

AMERICA

AN INTRODUCTION TO FEUDS, BITTERNESS AND SELF-GLORIFICATION