To Ames

Contents

In the main text:

Dearborn refers to Mailer: A Biography by Mary Dearborn (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999).

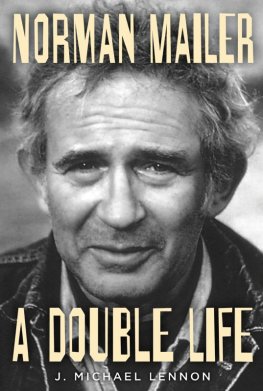

Lennon refers to Norman Mailer: A Double Life by J. Michael Lennon (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013).

Manso refers to Mailer: His Life and Times, edited by Peter Manso (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985).

Mills refers to Mailer: A Biography by Hilary Mills (New York: Empire Books, 1982).

Rollyson refers to The Lives of Norman Mailer by Carl Rollyson (New York: Paragon House, 1991).

AFM refers to Advertisements for Myself by Norman Mailer (New York: Putnam, 1959).

MoO refers to Mind of an Outlaw by Norman Mailer (New York: Random House, 2013).

Other in-text references are either set down in full in brackets especially with newspaper or magazine pieces or ascribed by abbreviation to fully specified works in the Bibliography.

Dai Howells has been of great help: diolch yn fawr. Thanks are due also to Penny Stenning. Jayne Parsons, my editor at Bloomsbury, has been enthusiastic and patient as usual; she has worked intrepidly at the production stage, as has Patrick Taylor. Im grateful to Lisa Verner of Ulster. Amy Burns made it possible. Any errors are my own.

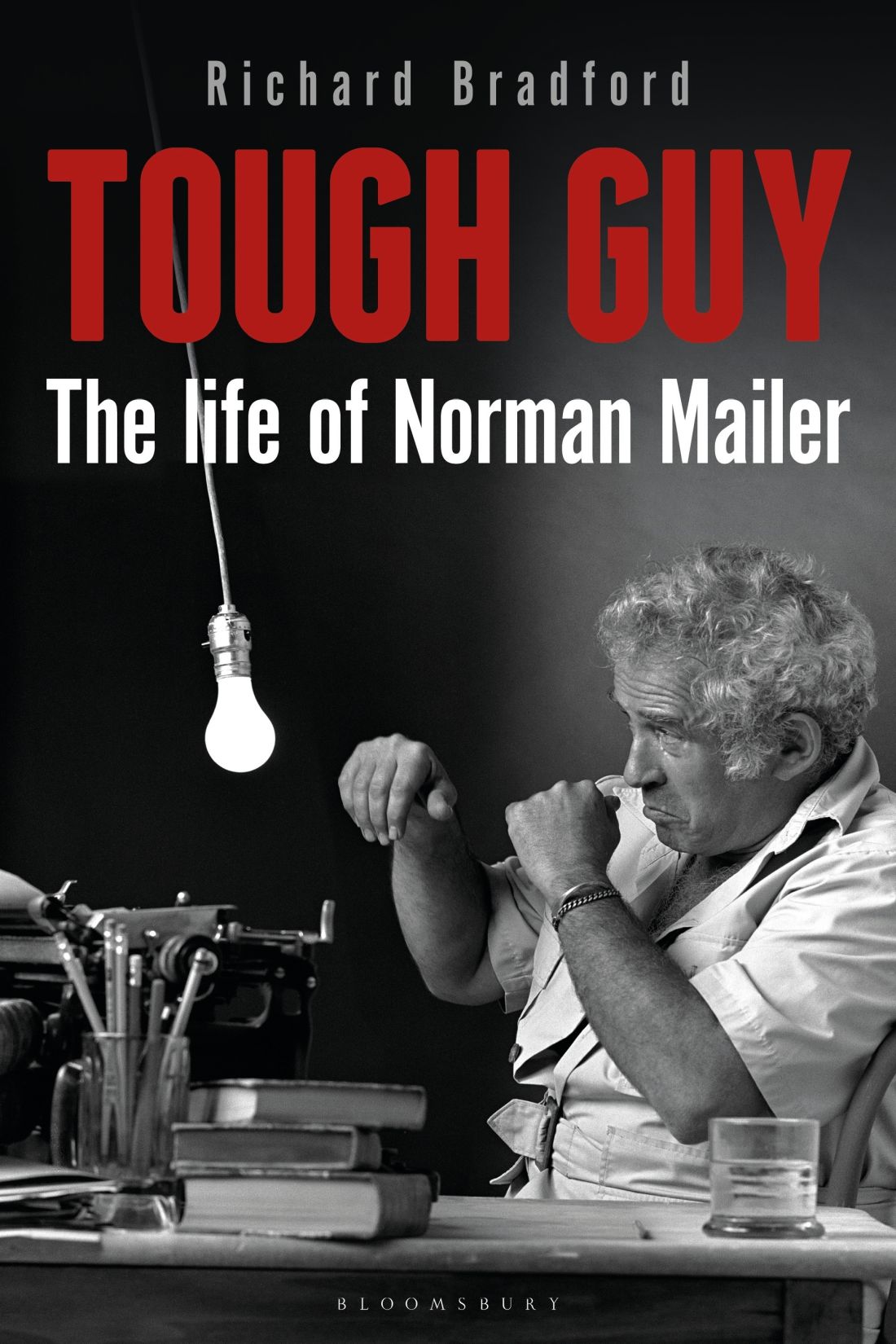

In his Manhattan office a literary agent is concluding a phone call with his client on her recently delivered novel.

Im sorry, but you must realise Your story is not credible, its too fantastic, ridiculously improbable. It was supposed to be a realistic portrayal of the world of books but its as far-fetched as science fiction. No one will publish it.

The book in question is about a fictitious novelist who visits his most hostile reviewers at their homes, taking with him a pickaxe handle. One has been hospitalised. Drinking at least a bottle of whiskey a day, supplemented by generous amounts of amphetamines and cocaine, he has broken records as a lothario, treating each of his numerous marriages as an incentive for a new regime of rabid infidelity. He subjects virtually all other members of the literary world to abuse, in print and in person, and those courageous enough to attend his parties are often treated to the spectacle of him naked, fulminating on the colossal proportions of his penis. The novel culminates at one of these events, when he partially severs the hand of a literary rival with a samurai sword. After calling an ambulance he decides to finish the job but being unsteady from drink and drugs visits only minor damage to the soft tissue of his victims side. The media-swamped trial for attempted murder results in him being found not guilty, and some argue that the jury is stacked with compulsive fans of his work.

The story concludes with him being elected as Governor of New York State. His vision alarms even the more radical elements of his party, promising, as he does, to campaign for the public flogging of paedophiles, free medical treatment for the illness of homosexuality, and legalised bear-baiting in Central Park.

Following his lunch the agent thinks of telephoning his client to pacify her and perhaps discuss how this disastrous project might be salvaged. Fifteen per cent of even a modest advance is still worth fighting for. But then, quite suddenly, he realises that nothing at all can be done. It is not that this monstrosity goes beyond the usual boundaries of fictional credibility. Rather, it comes too close to the truth: the novel might be deemed libellous as a thinly disguised biography of Norman Mailer.

Mailer was boundlessly provocative in his dealings with virtually everyone he knew, including his six wives. Shortly after his first novel, The Naked and the Dead (1948), brought him acclaim, he invited the poet Dorothy Parker to his New York apartment for drinks. Parker and her tiny poodle were introduced to Bea, Mailers pregnant first wife, and Karl, his gigantic, restive German Shepherd. Soon the conversation was suspended while Mailer did his best to restrain Karl, who after taking a sniff at Parkers dog made a frenzied decision to eat it. The incident lodged in Parkers memory, and as reports of Mailers ostentatiously bad behaviour became commonplace, the boundary between Karl and Mailer began to fade. She is supposed to have been particularly amused by a story that circulated during the early 1960s. Mailer had himself acquired two poodles, and one night after walking them in Central Park returned home in ecstasy with his left eye almost out of its socket. He had, he informed his wife, taken on two sailors who had accused my dogs of being queer.

Mailer tried on two occasions to become mayor of New York City. His first attempt in 196061 got no further than an inaugural party-lunch for the campaign. Along with the standard assembly of political bigwigs and journalists Mailer invited a considerable number of the citys disenfranchised, notably drunks and figures with criminal records whom he had met during his research, mostly in bars in the less fashionable parts of the metropolis. These were the kind of people whose interests he claimed to represent, but at the party most seemed more interested in the free drink. Several fights broke out, often involving Mailer, and in the early hours he staggered, bloodied, into the kitchen and stabbed his second wife, Adele, twice with a knife. His motive remains open to speculation since all witnesses were drunk, but Adele herself later wrote that when he ran towards her she treated this as another brash machismo performance. She recalled that he looked like a crazed bull, and she joined the game as the matador. Aja toro, aja, I called, come on, you little faggot, wheres your cojones, did your ugly little mistress cut them off? (The Last Party, p. 351). She saw it as imbecilic and ludicrous, but not once did she expect that he would actually use the knife. She required emergency surgery the wound came within a fraction of an inch of her heart but refused to press charges. Mailer pleaded guilty to a minor charge of assault and was given a suspended sentence.

In 1969 he ran again and came fourth in a field of five. His plans involved turning New York City into the fifty-first state and seeking more devolution than any of the other fifty. The city would, he hoped, fragment into self-governing, village-like communities where everyone would have a say in matters ranging from water fluoridation to capital punishment. Private automobiles would be banned from the streets of Manhattan, residents would have free use of communal bicycles, and non-profit markets would sell fresh vegetables grown in farms surrounding the metropolis.

His vision, as some credited it, had evolved out of his long-term commitment to very un-American notions of socialism, and he now sounds like a trailblazer for radical Green policies. But, like most of Mailers visionary enterprises, zealotry was matched by farce. Every month would contain one Sweet Sunday, during which all incoming and outgoing trains, road traffic, ships and air transport would be banned. To encourage the urban population to sample the organic, unpolluted experience enjoyed by countryfolk, electricity would be turned off too. At one public meeting he was asked by a nonplussed voter how those in cramped apartments, let alone hospitals, would cope without air conditioning when high-summer temperatures hit the 90s. On the first hot day the populace would impeach me! he replied. Following several other anxious enquiries he grew impatient, informing a woman who asked how snow would be cleared without ploughs in midwinter that Id piss on it. During the 1960/61 election he had petitioned for the recognition of communist Cuba and declared that the new, quasi-independent New York City must form an alliance with Castros republic, given their similarities.

Next page