First Sight

A s a boy of fourteen in 1977, I sat with my mother in our living room at home in Oregon to watch the Academy Awards. The show was a tradition we looked forward to each year, but this particular broadcast was special. The newspaper had said that my hero, my favorite writer, would appear that evening to present the Best Documentary award. I could narrowly manage my excitement about seeing Lillian Hellman on television for the first time.

Just before Christmas the previous winter Id borrowed my mothers copy of Hellmans autobiographical book Pentimento . Upon reading the last line of her opening paragraphI wanted to see what was there for me once, what is there for me nowI was hooked. My mind was too young to grasp the complexity of reflection through the tortures of time, but that was not essential. What was relevant was that I had, for the first time, been seduced by words that were at once severe and tenderly measured. By springtime, I was almost obsessed with the womans writing and I needed to see how she carried herself on television. Did she move her hands when she spoke? Would her voice be as riveting to my ears as her written words were to my eyes? By seeing her, might I better understand why her prose penetrated me so deeply, tormented me like a secret lust? I had pledged loyalty to a writer for the first time.

Then, onto the TV screen walked an unusual looking but finely dressed man with a scrunch of graying hair and electric, all-consuming eyes. In an exceptionally urgent tone, he began to address the millions who were watching, prior to presenting an award for screenwriting, but I had a hard time processing all he was saying. It struck me that he could not possibly be as remarkable as he presented himself to be, with his hurried speech and cultured coolness. There is no doubt that I was cynical toward him then, but I couldnt stop watching.

Who is that? I asked my mother.

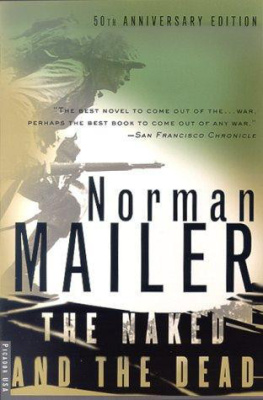

Thats Norman Mailer, she said. He wrote The Naked and the Dead . You should read it.

Without a doubt, the name of Norman Mailers book was stimulating. It excited me while sparking an unexpected embarrassment. The words had sprung without hesitance from my mothers lips: The NAKED and the DEAD. That title kicked up a whole host of primitive sensations in me. The words twisted me up and forced me down an avenue of thought more dangerous than the obscure title Pentimento ever could.

Lillian Hellmans work captivated me, but held me in an unruffled shelter. Her writing had become like an addiction for me, so this unfamiliar author on the television, and his suggestively titled book, would have to get in line. I remained faithful to Hellmans works for several years after that. Then, after my reading of her was complete, The Naked and the Dead arose again. That was the year I graduated from high school.

I heard an utterly scoundrel voice when I read Norman Mailers war book, a complex novel hed written at age twenty-five, seven years older than I was when I finally gave it a chance. While reading it, I realized the extent to which involved, fractured prose could also be seductiveand maddening! I didnt finish it until years later, and well after devouring the works of Dashiell Hammett, Ernest Hemingway, Irving Stone, and several others. But The Naked and the Dead and the man who wrote it lingeredsmoldered, evenin the dark of my mind.

I have no vivid recollection of seeing Lillian Hellman on television that night. Whom I do recall clearly is Norman Mailerthe novelist who spoke fast and wrote a tough book. And as decades passed after encountering him that first time, I could not know that I would ultimately develop what can only be described as a paternal affection for the man. Worse, when I did give in to that fondness, I was privately riddled with silly guilt that I had never forgiven him for being so difficult to read in my youth. To me it seemed his book should have been easier since he was absurdly young when he wrote it. Rules, however, are not rational when it comes to relationships between writers and their readers. For me to digest that notion would require an unusual course of studythroughout which I would know him finally, and multifariously, as Norman.

I encountered him at dusk, near a heap of bananas. To be precise, however, our first real introduction occurred on a bitter spring night three years earlier in 2000, when I worked as a waiter at a small Cape Cod restaurant called the Commons. Norman Mailer, his wife, and two guests had come in to dine. It was the end of April, the last lingering period of our winter season, a sluggish and difficult time for business in Provincetown, which is mainly a summer destination. The town sits isolated at the tip of the Cape, bordered by beaches that are inviting in temperate months and merciless the remainder of the year. In gray, squally periods the seclusion can be brutal; trophy houses sit vacant, narrow streets are deserted, and the three thousand folks who tough winter out adjust their lives accordingly as the economy dwindles amid shortening days. For those who live and work here, the shift in seasons requires a sturdy disposition. Often residents invent private rules for survival by weighing financial gain against how much work is required to accomplish a task; time becomes precious as the urge to return home to hibernate the winter out takes hold.

The evening Mr. Mailers party came to eat, the buzz around the waiters station was that no one wanted any more customers. It had been yet another unprofitable wait shift, and the Mailers might stay well after closing. At best, the table would be worth a twenty for the extra hours. A fellow waiter, Margaret, a small woman with a large mouth, popped off, Besides, everyone knows Mailer is difficult!

I had no basis for what to think about Norman Mailer. I knew he lived in town, but Id never seen him and knew nothing about how he lived. I figured if he was crazy enough to stay here all winter long, he was probably a fairly regular guy. There were the few stories Id heard about him shopping at the A&P or chatting in line at the post office with townies. That information didnt exactly inspire images of abstract fame or swollen ego that one often attaches to celebrity, but what did I know? Margaret said he was difficult, and since she was more or less a dependable busybody there must be some nugget of truth to it.

As I watched Mr. Mailer plot his way to the table nearest the window with the aid of two canes, it seemed to me that this elderly man with white hair, stout mass, and wide smile could not possibly be a tricky customer. I was impressed by the way he gestured for his wife to sit first and then inquired about the comfort of the others before he took his own seat. Mr. Mailer seemed refined and generous, and his well-mannered disposition was unmistakable.

The memory of seeing him on television when I was a boy came flooding back as I watched from a distance. I could scarcely equate him now to the quick-tongued man who remained as a shadow on my brain. Id read some of his other works in the years between then and now, and I was inclined to distrust the accounts Id also read about his supposed antics. I was aware that much of what is written about famous people is often completely made up or an exaggerated version of a cluttered truth. Considering that, I trusted my gut.

I had a tendency to respect writers more than most artists, because I knew, in a small way, how difficult the business was. Id worked as a writer in several careers by then, scripting copy for a television show and stinting as an assistant managing editor for a small Boston newspaper, to mention two. I admired anybody who wrote for a living (not to mention a solid living). Lastly, I held an express appreciation for Norman Mailers work. Perhaps chance or enigmatic design had entered the picture, but on the evening Mr. Mailer entered my restaurant, The Gospel According to the Son sat three-quarters finished on my bedside table. A friend, a particularly pleasant woman who was not outwardly devout but nonetheless obdurate in her Catholic faith, had loaned it to me. It touched me, she said when she passed it on. But Im not sure I understand it all.