Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the memory of

David C. MacNeill (18821980)

and

James J. Loving, Jr. (190880)

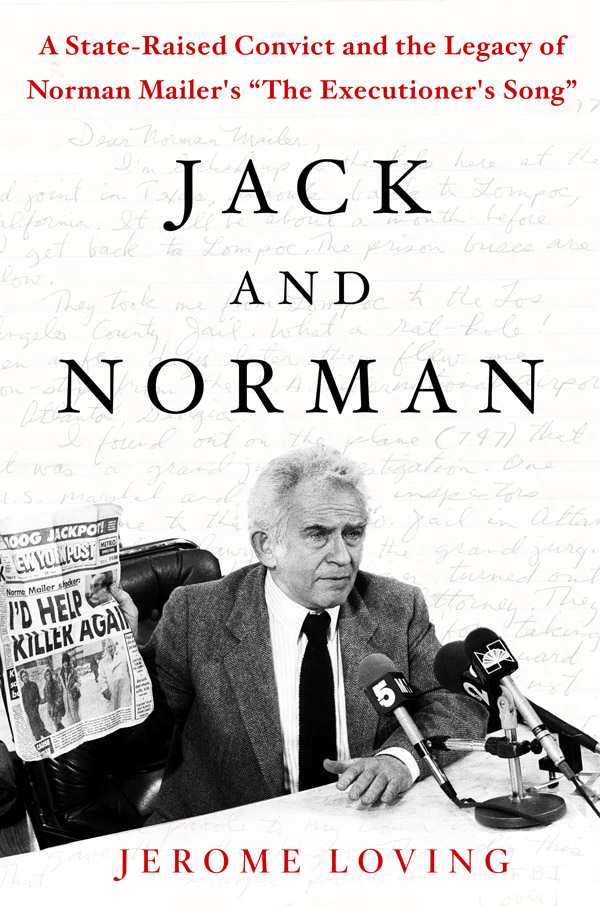

An awful lot of people are going to resent this book and theyre going to say theres something just swinish about glorifying a two-time killer and a bad man, and Im not certain that you can defend yourself against that absolutely.

NORMAN MAILER

Early on the morning of Saturday, July 18, 1981, sometime between 5:00 and 6:00 A.M ., two men would quarrel in a restaurant. Apparently, the dispute was over the use of the bathroom at the former Binibon Caf, an all-night joint on the corner of East Fifth Street and Second Avenue in the then seedy East Village of Manhattan. Both individuals were artists. Richard Adan, managing his father-in-laws restaurant, was an migr of Cuba and an aspiring playwright. Jack Henry Abbott, who had been recently released from prison after twenty years, hoped to immigrate to Cuba and was the author of the newly published In the Belly of the Beast: Letters from Prison . Adan had yet to make his mark as an artist but was on his way. Abbott, who had taught himself to write in prison, had just produced a bestseller. The New York Times Book Review for the next day printed an ecstatic appraisal, which New Yorkers would wake up to read before they heard the very latest news about the author.

The men quickly moved their argument outside, where Adan tried to calm the waters by showing Abbott a place behind a Dumpster where he could relieve himself. While doing so, Abbott worried that Adan was going to attack him or have him arrested for disorderly or threatening conduct since, inside, he had raised his voice when Adan refused to let him use the employee bathroom. He also worried about what the two young ladies sitting at one of the tables inside were thinking. One was a student at Barnard and a native of the Philippines and the other a resident of France, who had accompanied him to the caf after a night of dancing. Later, Abbott claimed Adan had a knife. Abbott definitely had a knife. Emerging from behind the Dumpster, he again confronted Adan, his anger at being refused use of the facilities in front of his female guests still smoldering. This time, the soft-spoken night manager tried to diffuse the situation by turning his back on Abbott while inviting him to return to the restaurant. Suddenly, Abbott pulled out a four-inch blade, grabbed his victim from behind, and plunged the knife into his chest, nearly slicing Adans heart in half. Abbott ran back into the restaurant and announced that he had just killed a man and had to flee. The young women fled, too, but they didnt leave the area; instead, they stood a block away looking back at the scene of the attack until somebody identified them to police as appearing to have knowledge about the crime and they were brought back for questioning. Adan lay dead on the littered pavement. Abbott would soon be on his way to Mexico.

* * *

Thus began and ended the brief and fleeting literary career of Jack Henry Abbott, even though he would write another book a few years later. That morning also changed forever the way Norman Mailer would view the artist or the writer as outlier, an idea he had asserted in the controversial essay The White Negro in 1959. Literary talent might not, should not, trump personal conductthe man who had once stabbed his wife, nearly killing her, would conclude. Mailer had been one of the principal agents of Jacks release from prison. He had promised to employ the ex-con as a literary assistant, and he had written an introduction to In the Belly of the Beast . The book consisted of prison letters Abbott had written to Mailer while he worked away on The Executioners Song , his magnum opus and the work that would win him his second Pulitzer Prize, in 1980. Without those letters from Abbott, who told him what it was truly like to grow up behind bars, as Gary Gilmore, the focus of The Executioners Song, had essentially done, Mailer said he could not have written the book he did. Your letters, he told Abbott as he was finishing his work, have lit up corners of the book for me that I might otherwise not have comprehended or seen only in the gloom of my instinct unfortified by experience. Often the things you say corroborate my deepest instincts about what prison must be like. Although he had spent brief time in city jails and seventeen days in Bellevue Hospital following the stabbing of his second wife in 1960, Mailer had never been in prison. Abbott and Gary Gilmore were incarcerated in the same prison at the same timetwo, in fact: the Utah State Prison in Draper and the United States Penitentiary in Marion, Illinois.

When you got down to it, Mailer wrote in the introduction to Jacks book, I did not know much about violence in prison. He read carefully Abbotts letters describing it, which Mailer wrote, did not encourage sweet dreams. Unlike Gilmores description of prison in his letters to his girlfriend, Abbotts were not romantic. Abbott was not interested in the particular, as Gilmore was, but only in the relevance of those particulars to the abstract. Prison, whatever its nightmares, was not a dream whose roots would lead you to eternity, but an infernal machine of destruction, a design for the Dispose-All anus of a prodigiously diseased society.

* * *

This is the story of the author and the apprentice. It is the story of literary influence and tragedy. It is the story of a state-raised convict, the by-blow, as Melville says of another of societys orphans in Billy Budd, a novel that comes into play in our story; of an army drunk; and a Eurasian prostitute. It is the story of a writer who set out all his life to write the Great American Novel and stumbled into its greatness as essentially a gifted journalist whose true life novel transcends the quotidian world of facts. Finally, it is the story of incarceration in America.

Norman Mailer was less than halfway through a first draft of The Executioners Song , a book of just over a thousand pages, when he heard from Federal Prisoner 87098-132. Violence in America: A Novel in the Life of Gary Gilmore was then the working title for what would arguably become Mailers magnum opus. As in the case of his book on Marilyn Monroe in 1973, the author got the basis of his story from Lawrence Schiller, a photographer for Life magazine and a media entrepreneur. Schiller had purchased the rights to the Gilmore story. The convicted double murderer was executed by a Utah firing squad on January 17, 1977. It was the first use of capital punishment in the United States since 1973, when the Supreme Court had ruled the death penalty as it was then practiced cruel and unusual punishment, in part because of a lack of uniform criteria. The states, especially Texas, where Gilmore was born, quickly rectified the problem, and the high court approved the changes in 1976. Yet even Texas, which has easily led the field in executions since their resumption, took another six years to execute somebody. No one state, certainly not Utah, apparently wished to be the first to resume the death penalty in America. When Gilmore insisted that his sentence be carried out on schedule, bypassing the normal appeal process, he became a household name, his death wish sounded around the world, his picture splashed on the cover of Newsweek and most tabloids. He was quoted as telling the judge who had delivered the death judgment: You sentenced me to die. Unless its a joke or something, I want to go ahead and do it.