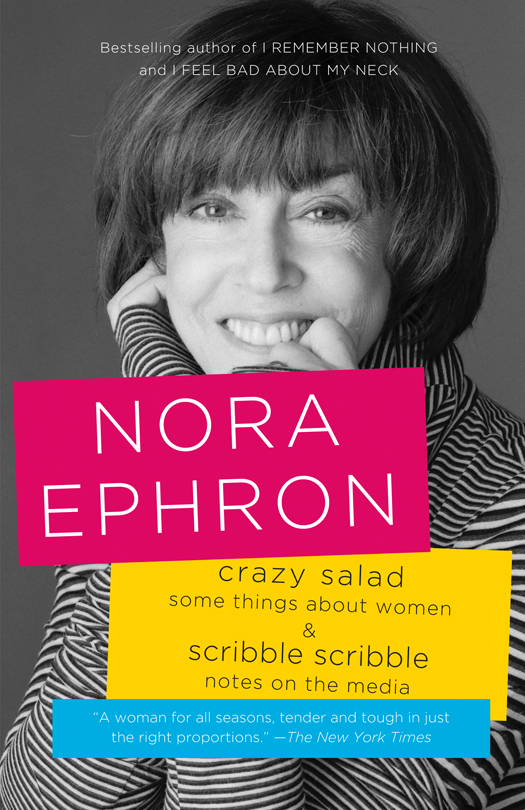

BOOKS BY NORA EPHRON

FICTION

Heartburn

ESSAYS

I Remember Nothing

I Feel Bad About My Neck

Nora Ephron Collected

Scribble Scribble

Crazy Salad

Wallflower at the Orgy

DRAMA

Love, Loss, and What I Wore (with Delia Ephron)

Imaginary Friends

SCREENPLAYS

Julie & Julia

Bewitched (with Delia Ephron)

Hanging Up (with Delia Ephron)

Youve Got Mail

(with Delia Ephron)

Michael (with Jim Quinlan, Pete

Dexter, and Delia Ephron)

Mixed Nuts (with Delia Ephron)

Sleepless in Seattle (with David S.

Ward and Jeff Arch)

This Is My Life

(with Delia Ephron)

My Blue Heaven

When Harry Met Sally

Cookie (with Alice Arlen)

Heartburn

Silkwood (with Alice Arlen)

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, OCTOBER 2012

Crazy Salad copyright 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975 by Nora Ephron

Scribble Scribble copyright 1975, 1976, 1977,

1978 by Nora Ephron

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Crazy Salad was originally published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1975. Scribble Scribble was originally published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1978.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of Crazy Salad have appeared in Esquire magazine, New York magazine, and Rolling Stone.

The articles in Scribble Scribble have been previously published in Esquire magazine, except Gentlemans Agreement which appeared in MORE magazine.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Viking Press, Inc., for permission to reprint ten lines of poetry from

The Portable Dorothy Parker. Copyright 1926, renewed 1954 by Dorothy Parker.

The stories in Scribble Scribble have been previously published in Esquire magazine.

The Cataloging-in-Publication data is available at the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-0-345-80473-0

Cover design: Abby Weintraub

Author photograph Elena Seibert

v3.1

Contents

Crazy Salad

For my sisters:

Delia, Hallie, and Amy

Its certain that fine women eat

A crazy salad with their meat

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

Crazy Salad

Preface to Crazy Salad

I began writing a column about women in Esquire magazine in 1972. The column was my idea, and I wanted to do it for a couple of specific, self-indulgent reasons and one general reason. Self-indulgent specifics first: I needed an excuse to go to my tenth reunion at Wellesley College, and I was looking for someone to pay my way to the Pillsbury Bake-Off. Beyond that, and in general, it seemed clear that American women were going through some changes; I wanted to write about them and about myself. When I began the column, the womens movement was in a period of great activity, growth, and anger; it is now in a period of consolidation. The same is true for me, and it has something to do with why it has become more and more difficult for me to write about women. Also, Im afraid, I have run out of things to say.

There are twenty-five articles in this book that glance off and onto the subject of women, and as I go through them, I can think of dozens of others I could have done instead. I dont deal with lesbianism here and, except peripherally, I dont deal with motherhood. Month by month, I took what interested me most, and so I never wrote about a number of things that interested me somewhat: panty hose, tampons, comediennes, the Equal Rights Amendment, Fascinating Womanhood, Bella Abzug, The Story of O, the integration of the Little LeagueI could go on and on. The point here is simply to say that this book is not intended to be any sort of definitive history of women in the early 1970s; its just some things I wanted to write about.

A Few Words About Breasts

I have to begin with a few words about androgyny. In grammar school, in the fifth and sixth grades, we were all tyrannized by a rigid set of rules that supposedly determined whether we were boys or girls. The episode in Huckleberry Finn where Huck is disguised as a girl and gives himself away by the way he threads a needle and catches a ballthat kind of thing. We learned that the way you sat, crossed your legs, held a cigarette, and looked at your nailsthe way you did these things instinctively was absolute proof of your sex. Now obviously most children did not take this literally, but I did. I thought that just one slip, just one incorrect cross of my legs or flick of an imaginary cigarette ash would turn me from whatever I was into the other thing; that would be all it took, really. Even though I was outwardly a girl and had many of the trappings generally associated with girldoma girls name, for example, and dresses, my own telephone, an autograph bookI spent the early years of my adolescence absolutely certain that I might at any point gum it up. I did not feel at all like a girl. I was boyish. I was athletic, ambitious, outspoken, competitive, noisy, rambunctious. I had scabs on my knees and my socks slid into my loafers and I could throw a football. I wanted desperately not to be that way, not to be a mixture of both things, but instead just one, a girl, a definite indisputable girl. As soft and as pink as a nursery. And nothing would do that for me, I felt, but breasts.