Table of Contents

PENGUIN TWENTIETH-CENTURY CLASSICS

COMPLETE STORIES

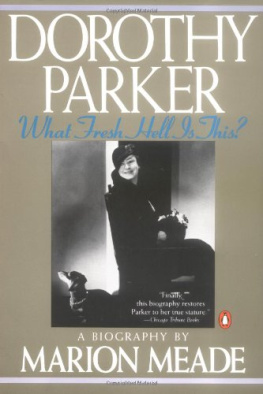

Dorothy Parker was born to J. Henry and Elizabeth Rothschild on August 22, 1893. Parkers childhood was not a happy one. Her mother died young, and Dorothy did not enjoy a good relationship with her father and stepmother. She began her education at a Catholic convent school in Manhattan before being sent away to Miss Danas School in Morristown, New Jersey. In 1916, Frank Crowninshield gave Parker an editorial position at Vogue , following its publication of a number of her poems. The following year she moved on to write for Vanity Fair , where she would later become the theater critic. That same year she met and married Edwin Pond Parker II, whom she divorced a few years later. It was at Vanity Fair that Parker met her associates with whom she would form the Algonquin Round Table, the famed New York literary circle. In 1925, Parker also began writing short stories for a new magazine called The New Yorker . Her relationship with that publication would last, off and on, until 1957. Parker went abroad in the 1930s, continuing to write poetry and stories. In Europe she met Alan Camp-bell, whom she married in 1933. The couple divorced in 1947 but remarried in 1950, remaining together until Campbells death in 1963. Throughout this period in her life, Parker continued to publish collections of her work, including Enough Rope (1926), Sunset Gun (1928), Laments for the Living (1930), and Death and Taxes (1931). Her last great work was a play, The Ladies of the Corridor , which she wrote with Arnaud dUsseau, published in 1954. Parker died on June 7, 1967.

Colleen Breese teaches in the English Department at the University of Toledo and is the author of Excuse My Dust: The Art of Dorothy Parkers Serious Fiction . She resides with her family in Sylvania, Ohio.

Regina Barreca, a professor of English and feminist theory at the University of Connecticut, is the author of Sweet Revenge: The Wicked Delights of Getting Even , Untamed and Unabashed: Essays on Women and Humor in Literature , Perfect Husbands (and other Fairy Tales) , and They Used to Call Me Snow White , but I Drifted . She lives with her husband in Storrs, Connecticut.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road,

Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

First published in Penguin Books 1995

Copyright The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 1924,

1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1937, 1938, 1939,

1941, 1943, 1955, 1958, 1995

Introduction copyright Regina Barreca, 1995

All rights reserved

The Custard Heart was originally published in Dorothy Parkers Here Lies , The Viking Press, 1939. The other selections first appeared in the following periodicals: American Mercury , The Bookman , Cosmopolitan , Esquire , Harpers Bazaar , Ladies Home Journal , The New Republic , The New Yorker , Pictorial Review , Scribners , Smart Set , Vanity Fair , and Womans Home Companion .

The Banquet of Crow is As the Spirit Moves,

An Apartment House Anthology, Men Im Not Married To, Welcome Home, Our Own

Crowd, and Professional Youth are

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Parker, Dorothy, 1893-1967.

[Short stories]

Complete stories / Dorothy Parker ; edited by Colleen Breese ; with

an introduction by Regina Barreca.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-14403-9

1. United StatesSocial life and customs20th centuryFiction.

I. Breese, Colleen. II. Title.

PS3531.A5855A6 1995

813.52dc20 95-15524

http://us.penguingroup.com

INTRODUCTION

Why is it that many critics seem so intent on defusing the power of Dorothy Parkers writing that she appears more like a terrorist bomb than what she really is: one, solitary, unarmed American writer of great significance? Is it because so many of her criticsone might hesitate to underscore the obvious: so many of her male criticsseem to resent, half-consciously, her unwillingness to appease their literary appetites? Is it because Parker did not list among her many talents The Ability to Play Well with Others?

Dorothy Parker wrote strong prose for most of her life, and she wrote a lot of it, remaining relentlessly compassionate regarding, and interested in, the sufferings primarily of those who could not extricate themselves from the emotional tortures of unsuccessful personal relationships. Her stories were personal, yes, but also political and have as their shaping principles the larger issues of her daywhich remain for the most part the larger issues of our own day (with Prohibition mercifully excepted).

Parker depicted the effects of poverty, economic and spiritual, upon women who remained chronically vulnerable because they received little or no education about the real worldthe real world being the one outside the fable of love and marriage. But Parker also addressed the ravages of racial discrimination, the effects of war on marriage, the tensions of urban life, and the hollow space between fame and love. Of her domestic portraits one is tempted to say that, for Parker, the words dysfunctional family were redundant. She wrote about abortion when you couldnt write the word and wrote about chemical and emotional addiction when the concepts were just a gleam in the analysts collective eye.

Parker approached these subjects with the courage and intelligence of a woman whose wit refused to permit the absurdities of life to continue along without comment. Irreverent toward anything held sacred from romance or motherhood to literary teas and ethnic stereotypes Parkers stories are at once playful, painful, and poignant. Her own characteristic refusal to sit down, shut up, and smile at whoever was footing the bill continues to impress readers who come to her for the first time and delight those who are already familiar with the routine. Her humor intimidates some readers, but those it scares off are the ones she wouldnt have wanted anyway.

She didnt court or need the ineffectual. She would not, for example, have wept too long for having frightened good old Freddie from the sketch titled Men Im Not Married To. Freddie, she tells us, is practically a whole vaudeville show in himself. He is never without a new story of what Pat said to Mike as they were walking down the street, or how Abie tried to cheat Ikie, or what old Aunt Jemima answered when she was asked why she had married for the fifth time. Freddie does them in dialect, and I have often thought it is a wonder that we dont all split our sides. There, in brief, lies the difference between Parkers gift and much of what passed for humor in her own (and in our own) time: Parkers wit caricatures the self-deluded, the powerful, the autocratic, the vain, the silly, and the self-important; it does not rely on mean and small formulas, and it never ridicules the marginalized, the sidelined, or the outcast. When Parker goes for the jugular, its usually a vein with blue blood in it.

Certainly the portraits of deleriously pretentious intelligentsia Parker poured onto her pages tweaked at certain readers, and its probable that Parker herself was aware of the wince-inducing effect of some of her sharper prose as she left it out of the earlier collections of her work. What is certain is that a number of the stories printed here for the first time since their initial publication in various periodicals contain moments of satire so spectacular that those certain readers mentioned earlier might shrivel up in the manner of a vampire shown a silver cross.