Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

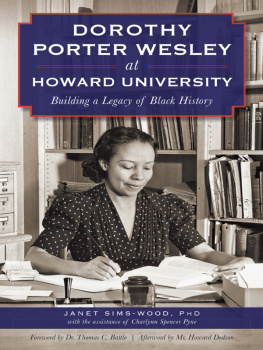

Copyright 2014 by Janet Sims-Wood

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.179.6

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.644.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to the African American teachers from Rutherford County, North Carolina, who taught during and after segregation and paved the way for the author.

Also dedicated to the staff (current and former) of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, which works to preserve and continue the legacy Dorothy Porter Wesley left behind.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

We value books and libraries, but we often overlook the custodians who collect and care for them so that the resources are available to us whenever we need them. We enjoy historical artifacts and documents that illuminate our past, but we often overlook those who preserve them. We marvel at the images captured in the various media we have developed, but we often ignore those who seek them out and save them for our enlightenment. We value the work of scholars who use the resources, but we tend to ignore the keepers and bibliophiles who make the scholarship possible. Many of these keepers (librarians, curators, archivists) had a wide-ranging knowledge of a myriad of subjects, which assisted researchers in probing more deeply into little-known and unknown areas of scholarship. Some of these keepers became scholars unto themselves. One was Dorothy Porter Wesley, a legend to scholars of black history and culture.

Dorothy Porter Wesley was part of a generation that helped to foster a new understanding of the black experience in Africa, the Americas and other parts of the world. Since much of the history of people of African descent was intentionally fabricated, ignored or obscured in efforts to justify enslavement, cultural ostracism and institutional racism, that history and materials documenting that history were essentially deemed of little or no importance. Efforts to correct this were hampered by indifference, intentional obfuscation, ignorance and a lack of oral, documentary and material evidence to substantiate claims that contradicted the notion that black people had no meaningful history and had made no significant contributions.

On the occasion of Porter Wesleys retirement from Howard University, historian Benjamin Quarles noted the formers contributions to Africana scholarship by opining that there was no significant work in black history in the postWorld War II era that did not acknowledge and benefit from her efforts. Those efforts extended beyond the collection of books, periodicals and published scholarship. Porter Wesley ferreted out and valued obscure items that scholars would later realize were valuable. These scraps of paper, letters, diaries, journals, scrapbooks, photographs and ephemeral items became the jewels of research. In addition to the wise counsel she offered, which reflected her own scholarship, Porter Wesley developed bibliographies and special library cataloguing that would better enable students and scholars of black history to access important information. Her accomplishments are reflected in the many awards she received from the various professional and scholarly communities that benefitted from her decades-long efforts.

Upon Porter Wesleys retirement in 1973, Howard University reorganized the collections she had overseen for more than forty years as the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center (MSRC). As the MSRC celebrates its centennial, it is only fitting that we reexamine a life of service that seems more a calling than a career. It is also fitting that Dr. Janet Sims-Wood authored this biography. She was inspired by Porter Wesley and mirrors her as she continues in the tradition of scholar/librarian.

THOMAS C. BATTLE, PHD

Retired Director

Moorland-Spingarn Research Center

Howard University

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

So many people contributed to the completion of this book. Thanks to Prince Georges Community College (PGCC) for the Pathfinder Grant that allowed me to travel to Yale University to conduct research in the Dorothy Porter Wesley Papers. Also, all of my co-workers in the PGCC library were very helpful and supportive, especially during the last weeks, when they graciously changed schedules to accommodate my time away from the library.

Ida Jones is responsible for introducing me to The History Press. I appreciate her support as I prepared my proposal and in guiding me to materials in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center.

I spent a week at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University conducting research in the Dorothy Porter Wesley Papers. I was only able to go through eighteen of the more than one hundred boxes of materials, but the staff was most helpful in getting me reproductions and photographs from this collection. Research librarian Karen Nangle was my contact person and worked to help me get research materials. I am truly grateful to all of the staff (librarians, technicians and security) for their assistance. Thanks to Yale student Julie Botnick for her insights on Porter.

My adopted son, Yohuru Williams, associate vice-president for academic affairs at Fairfield University, gave me the opportunity to speak to the students during my trip to Connecticut.

Thanks to Thomas C. Battle, retired director of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, who worked with Dorothy Porter during her last years at Howard University. He not only wrote the foreword but also gave personal perceptions on working with Porter.

The staff of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center went above and beyond the call of research assistance in helping me find information. Thanks to JoEllen ElBashir, Ida Jones, Kenvi Phillips and Richard Jenkins in the Manuscript Division; Clifford Muse, Tewodros Teddy Abebe and Lopez Matthews in the Archives; and Ishmael Childs and Amber Junipher in the Reference Department. All of you were most helpful, and I owe you a debt of gratitude for your unending support and for long-standing friendships. Current Moorland-Spingarn director Howard Dodson also provided the afterword.

Darlene Clark Hine, John Bracey, Sharon Harley, Randall Burkett, Ruby Sales, Dolores Leffall, Yvonne Seon, Elinor Des Verney Sinnette and Marilyn Richardson were so gracious in relating their personal experiences with Dorothy Porter. Their comments showed Porter as a real person.

W. Paul Coates, founder of Black Classic Press, gave special insight into the black bibliophiles whom Porter loved and on the Black Bibliophiles and Collectors symposium held at Howard University. He published two works by Portera reprint of her Early Negro Writing, 17601837 and William Cooper Nell, Nineteenth-Century African American Abolitionist, Historian, Integrationist: Selected Writings, 18321874, which was completed by Porters daughter, Constance Porter Uzelac.

Kenya King, journalist and actress, helped me find information on the White House photo Porter took with President Bill Clinton at the National Endowment for the Humanities Charles Frankel Prize celebration.

Next page