JAMES FISHER M.A.

JOHN GILMOUR M.A.

JULIAN S. HUXLEY M.A. D.Sc. F.R.S.

L. DUDLEY STAMP B.A. D.Sc.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EDITOR:

ERIC HOSKING F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalist. The Editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native fauna and flora, to which must be added concern for their conservation, are best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research. The plants and animals are described in relation to their homes and habitats and are portrayed in the full beauty of their natural colours, by the latest methods of colour photography and reproduction

R. S. R. FITTER is a young social scientist and writer who has been a naturalist all his life. Though he has never been in the strict sense a professional biologist, the study of animals and plants has occupied so much of his leisure that he can by no means be described as an amateur. Indeed, he holds two positions which, though honorary, are as onerous as they are importantthe Secretaryship of the British Trust for Ornithology and the Editorship of The London Naturalist, the journal of the London Natural History Society.

Mr. Fitter has always lived in London, as have his father, grandfather and great-grandfather; and he has made a special study of Londons natural historyand the history of its natural historyfor over ten years. He has, clearly, the material qualifications for the work he has chosen to do; and the reader will soon agree that he has done it well. And it is time that it was donehigh time that this book was written. For up to now there has been no real attempt, in any biological literature we are familiar with, to write the history of a great human community, in terms of the animals and plants it has displaced, changed, moved and removed, introduced, dispersed, conserved, lost or forgotten. In certain ways Mr. Fitters book makes gloomy reading, for the progressive biological sterilisation of London is a sad history. But the discerning reader will soon notice that the sterilisation is not complete. Indeed, in this remarkable history not all is on the debit side. There is the fascinating story of the adaptation of wild life to an environment which is almost wholly man-made. There is also the fact that London natural history to-day has its special compensations, even its new and particular treasures.

Mr. Fitters book is a notable contribution to the history and the understanding of the processes at work in the evolution of Londons wild life, and will be of help in the framing of any future policy.

THE EDITORS

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

LONDON is the largest aggregation of human beings ever recorded in the history of the world as living in a single community. In 1931, the date of the last census, not far short of nine million men, women and children were living within twenty miles of St. Pauls Cathedral. In no other area of equal size in the world are as many as 7325 people to the square mile to be found.

Such a huge mass of people cannot settle on the soil of a district without causing devastating changes in the natural communities of animals and plants that lived there before the men came. It is the main aim of this book to trace the story of these changes, to show the influence of man as a biotic factor in the most extreme example of urban development ever known. To do this it is first necessary to go back to the time when there was no human settlement on the present site of London. The spread of London, at first gradual, but latterly, especially in the past hundred years, relatively very rapid, is then chronicled. Finally, the present balance between man and the natural communities, showing the degree of adaptation which the latter have achieved, is described.

Up to the invasion of the Romans in A.D. 43 there is no certain evidence of the existence of any permanent settlement on the famous square mile of the City, which has been the core of London for the past nineteen hundred years. Vast changes had taken place in the flora and fauna of the lower Thames valley since the first men had come there some hundreds of thousands of years before, but they were due far more to long-term climatic trends than to any intervention of the men of the Stone, Bronze or Iron Ages. Man still fitted into an ecological niche among the other communities; he had not yet come to dominate them all.

With the coming of the Romans the first city was built on the twin hillocks on either side of the Walbrook rivulet, and man became a decisive influence within the wall that was built to enclose and protect Londinium. When the Romans left, and before the Saxons finally took possession, Nature must have reconquered much of her lost ground. From the seventh to the eleventh centuries there was much open ground within the City walls, but thereafter London not only filled out the space within its own walls, but overspilled, and began a rakes progress that is not ended yet, with almost continuous tongues of built-up area stretching from Hertford in the north to Reigate in the south, and from Tilbury in the east to Slough in the west.

Not the least interesting part of the story is the high degree of adaptation which the animals and plants of the lower Thames valley have shown to the immense changes wrought by man. Even where human activity has created wholly artificial habitats, a flora and fauna have in the course of centuries adapted themselves to conditions sometimes totally unlike anything normally found in Nature. The fauna of houses, and especially of warehouses, is extraordinarily varied and numerous. Three mammals, the black rat, the brown rat and the house-mouse, have succeeded in adapting themselves to a completely indoor existence, and a large number of invertebrates, spiders, flies, lice, bugs, clothes-moths, cockroaches, and so forth have done the same with varying degrees of success.

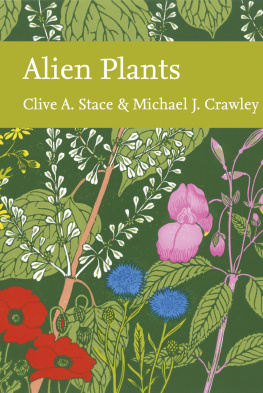

Out of doors, but still in areas completely or almost completely covered by roads, railways and buildings, three or four species of birds can live comfortably. This is true notably of the house-sparrow and the London pigeon, while the black-headed gull is developing a habitat-preference for railway sidings in the London area. Many of the lowlier plants, such as the mosses, also contrive to exist in habitats which simulate for them a rocky cliff or hillside, and wherever a bare patch of ground appears in the heart of the built-up area, a host of flowering plants, like the rose-bay willow-herb, Oxford ragwort, coltsfoot and Canadian fleabane, spring up in a remarkably short time.

Where the built-up areas are partially diluted with gardens, parks and other open spaces, several species of birds and innumerable insects and other invertebrates have carved out niches for themselves. The garden association of birds is now as definite an avifaunal community as that associated with heathland or sea-cliffs. It comprises the starling, greenfinch, chaffinch, house-sparrow, great tit, blue tit, mistle-thrush, song-thrush, blackbird, robin, hedge-sparrow, wren, house-martin and swift as permanent members, with other species, such as the linnet, pied wagtail, spotted flycatcher, willow-warbler and tawny owl often added. All these birds originally had quite different habitats, in woods or scrubland, or (in the case of the house-martin) on cliffs, but have quite adapted themselves to life in suburbia.

In the flower-beds, and wherever else man has broken the ground to make an artificial seed-bed, miniature forests of seedling plants arise. The weeds of cultivated ground are a community peculiarly dependent on human influence, and grow luxuriantly in a type of habitat which before man began to till the soil must have existed in the London area only as a result of rare accidents. They include such familiar pests of the gardener as the charlock, shepherds purse, chickweed, creeping cinquefoil, scentless mayweed, groundsel, sow-thistle, dandelion, field bindweed, speedwell, red dead nettle, greater plantain, white goose-foot or fat-hen, garden orache, broad dock, black bindweed, sun spurge and annual meadow grass. Some of these weeds are aliens that have followed man to most parts of the world where he has stayed to cultivate. Others have originated locally.