Contents

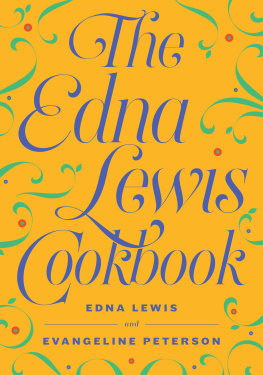

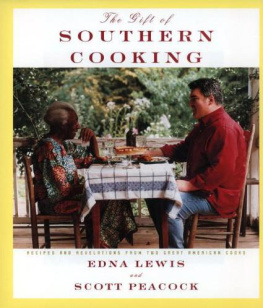

Edna Lewis

2018 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno, Chaparral, Challista Script, and SignPainter by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

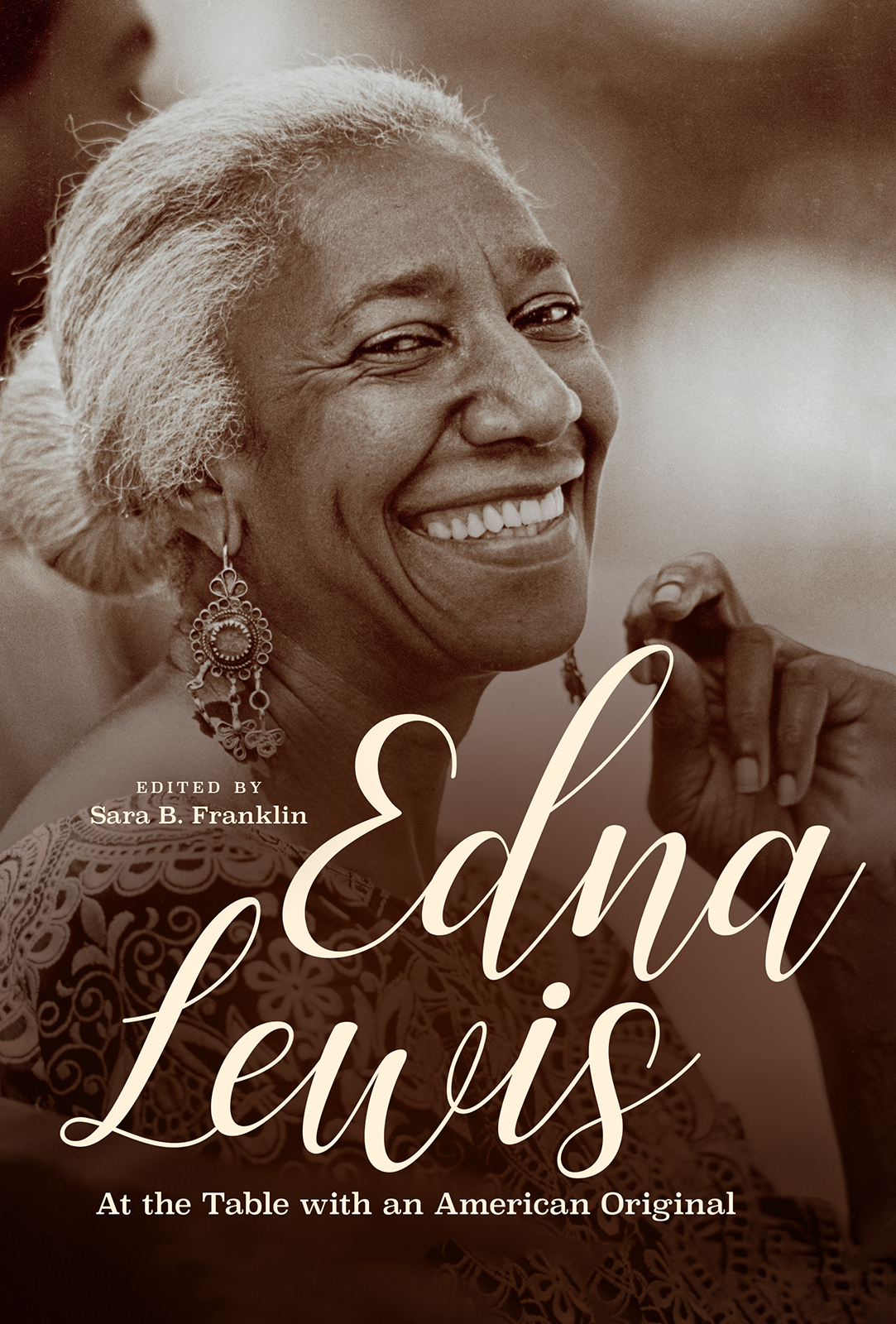

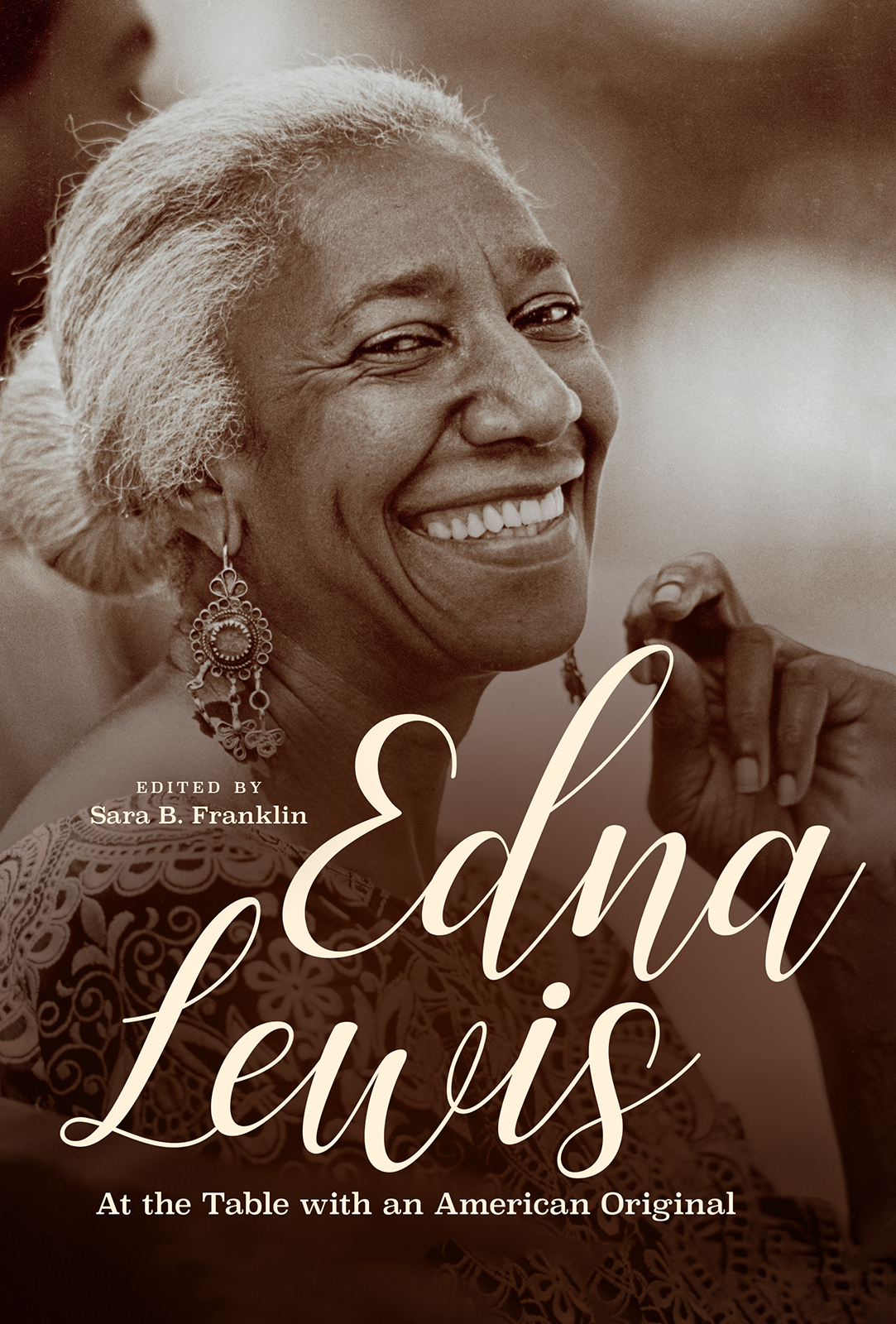

Cover photograph courtesy of John T. Hill

Frontispiece: Pen and gouache portrait of Edna Lewis by Amy C. Evans, 2017. www.amycevans.com.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Franklin, Sara B., editor.

Title: Edna Lewis : at the table with an American original / edited by Sara B. Franklin.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017036473| ISBN 9781469638553 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469638560 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Lewis, Edna. | African American cooks. | CookbooksHistory and criticism. | Cooking, AmericanSouthern style.

Classification: LCC TX649.L48 E36 2018 | DDC 641.5975dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036473

John T. Edges essay, Paying Down Debts of Pleasure, originally appeared in the Oxford American (Fall 2013); Francis Lams essay, Edna Lewis and Black Roots of American Cooking, originally appeared in the New York Times Magazine, October 28, 2015; and Susan Rebecca Whites essay, On Edna Lewiss The Edna Lewis Cookbook, originally appeared in Tin House 15, no. 3 (March 2014).

To all the women who have

ever put pen to paper,

or shared their knowledge and skills

through oral traditions,

to help us remember and perpetuate

the living art of cooking

Contents

Foreword

KIM SEVERSON

Death is the only sure measure of a persons worth. If youve lost somebody, you understand this. There you are at your grandmothers funeral, and someone youve never met before walks over and tells you about the day she stood up to a bully on an elementary school playground. Months after your husband passes, a note arrives in the mail expressing gratitude for the time he covered a friends rent without ever asking that the loan be repaid.

Only in hindsight do the bits and pieces of a life get uncovered, the parts coalescing into a new and more powerful whole. The good, strong, and brave arent always visible until they dont walk among us anymore. Then, like the winning numbers on a scratch-off ticket, the worth of a life is revealed. The prize was there all along, just under the surface.

The lens through which a persons life is viewed shifts with time. Consider Alexander Hamilton. He became a renegade hero to a generation of young people who drank up the Broadway musical in which the dusty story of Americas founding fathers was reimagined with black and Hispanic actors and set to a hip-hop soundtrack.

This is where we find ourselves when we consider with new eyes the life of Edna Lewis, which began on a Virginia farm in a small settlement called Freetown in 1916 and ended when she took her last breath in 2006 in a little apartment in Decatur, Georgia, a few days shy of her ninetieth birthday.

The facts of Miss Lewiss life havent changed since her death. She moved through the world as an African American woman only two generations out of slavery. She was deeply committed to social change. She was an artist and a fashion designer, a writer and a cook whose reach stretched from California to Africa. Her life took her from the soft dirt fields of her beloved rural home, where gathering, growing, and cooking was a form of family entertainment, to professional kitchens in Washington, D.C., New York, and, finally, Atlanta.

But what her life meant, and her influence on subsequent generations, has a new urgency at a time when the nation is looking again into the causes and effects of racism, and the history of the brutality laced through so much of the South she loved.

Miss Lewis cooked at a time when the simple, pure country food she was raised on and sought to teach became twisted into the cartoonish, corn-pone version that Cracker Barrel and Paula Deen would come to exploit or became the greasy, reductive manifestations of barbecue and greens found in urban soul food restaurants.

Miss Lewis knew southern food was neither of those things. She articulated, in a quiet, lyrical, and powerful way, that southern cooking could be as simple as a perfect peach pie but also as precise and elegant in its execution as any dish in the haute French culinary canon. Country cooking, when approached with unflinching purity and a dedication to technique, was delicious and important.

For students of southern culture, there is little argument that Miss Lewis was at the heart of a culinary renaissance that has led to a deeper appreciation of the regional nuances of cooking in the South. She helped nudge those in the North and on the West Coast to embrace the notion that eating must be connected to the seasons and the earth, and that country food should have a revered place on the American table.

The importance of Edna Lewis is shifting still. As the country finds itself again drilling down into its class and racial divisions, Miss Lewis and her story have taken on yet another layer of importance. Although food has always been cultural currency, it has never enjoyed the kind of crossover into the arts, politics, and health as it has in the past decade. How we eat has come to underscore issues of race, class, and environmental degradation. The pleasures of the table softly open hearts and give us a common language and a reason to have hard conversations about where our food comes from and who cooks it. Any knowledgeable eater these days knows that a bowl of shrimp and grits or a pot of gently simmering lady peas flavored with just a kiss of streak o lean, for example, has roots in the worst chapter of Americas history.

As cooks and scholars debate anew who owns southern food, Miss Lewis and her story offer a clear-eyed look back and a path forward. The life of an African American woman whose roots were firmly planted in garden soil and who cooked in countless kitchens with purpose and playful elegance becomes even more important. Her simple prose, her careful recipes, and her unyielding devotion to that which is both delicious and true mean more than they ever have.

Edna Lewis was a great cook in life. In death, she has become an even a greater teacher.

Introduction

SARA B. FRANKLIN

For me, it all began with a page of a magazine. It was January 2008. I was frozen deep in a Boston winter, paging through the issue of Gourmet that had just arrived in my mailbox and dreaming of new things pushing up through sun-warmed earth and the bite of somethinganythinggreen on my tongue, to shock me out of the dull gray of short, dark northeastern days. Instead of a taste, though, it was a question that awoke meHow did Southern food come into being?and a simple refrainSouthern is.... The piece was titled What Is Southern? and the author was Edna Lewis, an apparently esteemed cook and food writer Id never heard of from a regionthe American Southof which I knew nothing.

Her prose was feisty and provocative, wrought with exacting fineness. In What Is Southern? Edna Lewis spoke of a place, not merely through ingredients, but through culture as a wholeTruman Capote and wild watercress, Tennessee Williams and baked snowbirds; Lewis noted the forced history of illiteracy among black Americans in the same breath as some of the greatest names in American art and literature. There was no intent of irony here, but rather a distinct effort to broaden the purview of who and what was counted and accounted for in the measure of cultureBessie Smith, environmental stewardship, Louis Armstrong, culinary know-howand deep, deep knowledge of place buttressed it all.