THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

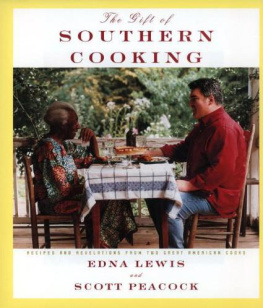

Copyright 2003 by Edna Lewis and Scott Peacock

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lewis, Edna.

The gift of Southern cooking : recipes and revelations from two great Southern cooks / by Edna Lewis and Scott Peacock. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-96271-3

I . Cookery, AmericanSouthern style. I . Peacock, Scott. II . Title.

TX715.2.S68 L45 2003

641.5973dc21

2002073153

PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS

The photographs reproduced in this book were provided with the permission and courtesy of the following:

Marion Cunningham:

John T. Hill:

Judith Jones:

Doug Snelgrove:

Personal collections of the authors:

All other photographs are by Christopher Hirsheimer.

v3.1

To Gertrude Moore

As God is my witness, Ill never be hungry again.

Scarlett OHara in Gone with the Wind

Contents

Introduction

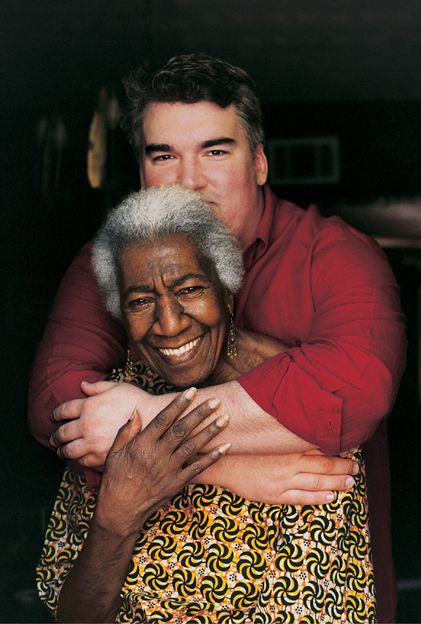

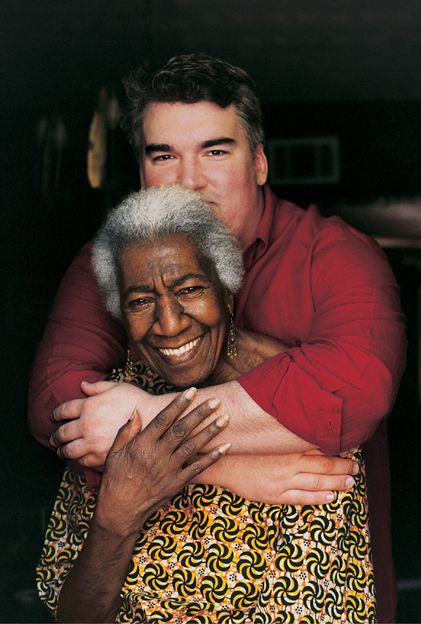

D uring the years that Edna Lewis and I have been friends and colleagues, we have cooked together and done a lot of research on the foods of the South. We werent surprised to discover how many different cooking styles and traditions, and how much diversity of ingredients, flavors, and cooking techniques there are throughout the southeastern states. In other words, Southern cooking is not a single cuisine.

In the South we are blessed with a long growing season and have always depended on fresh produce, both cultivated and wild. Theres an old saying that what grows together goes together, and the dishes we put on our tables have that natural seasonal affinity. We also tend to enjoy life at a leisurely pace. Good cooks in the South see the preparation of food as satisfying, a natural part of the rhythm of daily life. It is all of these qualities that we have tried to translate into the pages of this book so that you can really taste what good Southern cooking can be.

It has certainly been a process of discovery for me. Even being a Southerner myself, I didnt have a sense of the breadth and depth of the food. I first met Miss Lewis (as I always call her) in 1988, when she was already well known as an authority on the flavorful country cooking of Virginia. The truth is that at the time I wasnt even sure that Virginia was really part of the South. As a child in the southern reaches of Alabamaas Deep as the South getsall I knew of Virginia is that it lay far to the north and that Virginians (based on my mothers comments about a woman who lived in our little town) talked in a peculiar way. So I was surprised and delighted to find that Miss Lewis, whom I admired greatly as a writer and a chef, was as much a Southerner as I wasand she didnt talk funny at all.

What we further discovered as we came to know each other was that the foods that nurtured us reflected both the commonality and the diversity that makes Southern cooking so fascinating. For starters, it was quickly apparent that we came from Southern worlds as different as can be. Its nearly seven hundred miles from the now disappeared settlement of Freetown in north-central Virginia, where Miss Lewis was born and raised, to my hometown of Hartford, barely an hour from the Gulf of Mexico. As well, we were separated by generations and cultures. Miss Lewis, a grandchild of slaves, came of age in the 1920s in a nearly self-sufficient community that grew its own crops, raised and slaughtered its own animals, and preserved its own foods. My ancestors were also small subsistence farmers, but by the 1960s and 70s, when I grew up, our family had moved into town and ran a business that served the predominantly white farms around Hartford. We Peacocks enjoyed the convenient foods of the supermarket as well as the bounty of the land.

Miss Lewis and I found that our common food memories (like those of most Southerners) reflected this agricultural heritage, in particular the crops that built the Southcorn, root vegetables, legumes, leafy greens, fruits and berries, wheat, and ricealong with the cows and hogs that we all raised. We shared a deep appreciation for the foods of our childhood, such as cornbread, biscuits, greens flavored with smoked pork, fried chicken, flaky pies, hand-churned ice cream. And despite our generational differences, we both came from homes where the seasonal harvest was a ritual in which the children participated, where vegetables straight from the garden were often the main feature of the supper table, where skilled home cooking was admired and expected daily. And we realized that we both brought the values of home cooking to our work as chefs.

At the same time, we were aware of the differences in our family foods, shaped by geography, climate, and the farming economy. In Alabamas peanut country, oil was cheap and plentiful, so we used it freely as cooking fat. For Miss Lewis, lard and butter from their own livestock were generally used. They used more cream than we did, too. During our hot summers, greens grew bitter and lettuce bolted, so the only lettuce I ate was iceberg from the store, while cooked turnip and mustard greens served us during the cool months. Up in Freetown, they grew tender leaf lettuces for salad, and rape, kale, and turnip and beet greens went into the cooking pot, to which they added wild cresses, lambs quarters, and purslane. Asparagus also grew wild and Miss Lewiss mother cooked the slender spears in a skillet; not so my momat best she would occasionally open a can of asparagus onto a platter and serve it with mayonnaise (the only spears I ever saw, but I loved them).

Not that the Deep South isnt rich in other ways: we had fresh oysters and succulent fish from the Gulf in variety and abundance that Miss Lewis never imagined. And summertime in Hartford was filled with the delicious field peaslady peas, pink-eyed peas, Crowder peas, and a score of othersthat were cooked every day and frozen for the winter. Except for black-eyed peas, grown primarily as a cover crop, Miss Lewis never heard of these treasures.

There were cultural influences, too. At first, I was surprised that in humble Freetown, Miss Lewis enjoyed blancmange, brandied peaches, cats tongues, and beef la modedishes that were as familiar to her as grits, but utterly foreign to me. Later, as we began to trace the roots of Southern cooking in old recipe books, plantation journals, and slave narratives, the direct influence of English and French cookery in Virginia was clear. But in Alabama, the cooking was flavored with black Irish, Native American, Caribbean, and African influences.

Obviously this book is not a comprehensive compendium of Southern cooking. In our research we unearthed quite a few forgotten dishes that proved very appetizing, such as Caveach, or pickled fish, and Jefferson Davis Custard, which is particularly good with gooseberries. Many recipes come from regions that werent familiar to us until our work took us there, in particular the seafood specialties of the Carolina Low Country. But mostly we have focused on the foods we grew up with, the ones we love the most and believe are the staples of the Southern table. Some of the recipes belong to Miss Lewis and her family; others are mine or my mothers or Grandmaws. In several instances, you will find our quite different versions of related dishesthe Peacock cornbreads, for example, and the very different Virginia and Alabama fruit cobblers.

Next page