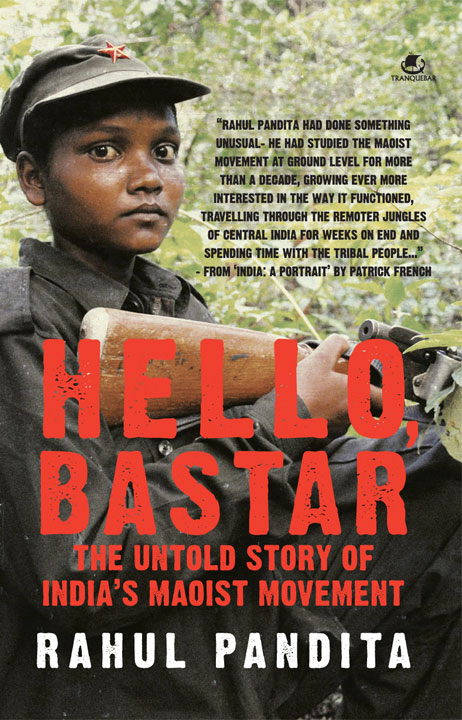

TRANQUEBAR PRESS

HELLO, BASTAR

Rahul Pandita is a senior special correspondent with the Open magazine. He is the co-author of the critically acclaimed book on insurgency: The Absent State. He has extensively reported from conflict zones ranging from Bastar to Baghdad.

HELLO, BASTAR

The Untold Story of Indias

Maoist Movement

Rahul Pandita

TRANQUEBAR PRESS

An imprint of westland ltd

Venkat Towers, 165, P.H. Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600 095

No.38/10 (New No.5), Raghava Nagar, New Timber Yard Layout, Bangalore 560 026

Survey No. A-9, II Floor, Moula Ali Industrial Area, Moula Ali, Hyderabad 500 040

23/181, Anand Nagar, Nehru Road, Santacruz East, Mumbai 400 055

47, Brij Mohan Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002

First published in TRANQUEBAR by westland ltd 2011

Copyright Rahul Pandita 2011

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-93-80658-34-6

Typeset in Aldine401 BT by SURYA, New Delhi

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers.

To Anu, and her imagined biscuits

Contents

Afterword: Comrade Anuradha Ghandy and the

Idea of Indiaby Kobad Ghandy

M y heartfelt gratitude, first of all, in Hyderabad, to Varavara Rao and Hemalata for putting up with me on so many early mornings and feeding me with the most delicious servings of curd-rice. Also to Ravindran, C. Prabhakar, and to Tirumalafor her courage.

To Comrade T. And, yes, I still await your manuscript.

In Nagpur, to Shoma Sen, Anil Borkar, and Surendra Gadling.

To Gurmeet, for his Hemingway's old man kind of charm.

In Dandakaranya, to those who know who they are.

To those who cannot be named in places like Warangal, Karimnagar, Adilabad, Khammam, Vizag, Gadchiroli, Bhamragarh, Bhadrachalam.

To Arundhati Roy, for the most insightful conversations over coffee and TV news humour.

To Patrick French, for his friendship and his belief in what I saw in Bastar.

To Hartosh Singh Bal, more of a brother than political editor.

To Anubha Bhonsle, for the imagery of Irom and Aai, and the wisdom of bread.

To Saurabh Kumar, for a motorcycle journey undertaken long ago.

To Pragya Tiwari, for the 'Unndres' in us.

To Neelesh Misra, harbinger of drama and dreams. And to Shilpa Rao, for music and muffins.

To the whole Kasauli gang, especially Preetie and Rajesh Dogar.

To my editor and guide Renuka Chatterjee, for succumbing to the idea of revolution.

To my parents, Shanta and P.N. Pandita, and to the storytelling techniques of my darling niece Sheranya.

And, to Pinky, for home, hearth, and happiness.

F or the convenience of readers, the terms 'Naxal' and 'Maoist' are used interchangeably throughout this book. This is common practice in the media and even the police. In fact, the Maoists too use both terms to define themselves. But the fact is that the current Maoist movement is bigger than the original Naxal movement in terms of its reach and strength. The Maoists have moved leaps ahead of their predecessors who were a part of the Naxalbari movement from where the word 'Naxalite' was coined. In that sense, the current 'Naxalites' are more 'Maoist' than Naxal.

To be radical is to grasp things by the root.

Karl Marx

Inside us there is something that has no name, that something is what we are.

Jose Saramago

T he spasms had been troubling him again. In fact, amoebic dysentery had been his constant companion, a result of a harsh life of more than three decades. And an enlarged prostate too. He was more comfortable with the pain these afflictions caused than the feel of the cold metal of a gun in his hands whenever he had had to hold it. But that was on very rare occasions, deep inside the forest along the Eastern Ghats: memorial meetings for fallen comrades, ceremonial parades or military drills. Presently, though, he was hundreds of miles away from the jungles of central India.

He was in Delhi.

The Molarband Extension colony of south Delhi's Badarpur area was a different kind of jungle. Early in the morning, thousands of men swarmed through the narrow, sewage-ridden roads, locust-like, on their ramshackle bicycles. They worked in factories as fitters or cutters or as daily wage labourers at construction sites or as private security guards. Life was tough. In recent times, it had become more difficult to survive, with the prices of food and daily necessities going through the roof. Many men stayed alone, leaving their families behind in small towns or villages. Fathers waiting for a little money to come by for a cataract operation. Widowed mothers. Unmarried sisters. Impoverished wives hoping to save enough for the education of children. Out of their meagre incomes, the men struggled to send as much money as possible to their families.

For years, the poor workers took solace from an old film song: Dal roti khao, prabhu fee gunn gao (Have dal-roti, sing paeans to the Almighty). But now with dal costing almost Rs 100 a kilo, the poor didn't know what to eat and in the cruel city, who to sing paeans to.

The city ran on a very complex arithmetic. It was a city drunk on power, a city from where a handful of people decided the fate of over a billion others, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, as messages painted on highways by the Border Roads Organisation would remind one. These few people were India's political leaders. Their abode was the Parliament in the heart of New Delhi, a place referred to as 'pigsty' by the man and his comrades.

On Sundays, the city's middle class would come out in hordes, in their small and big cars, enjoy ice cream at India Gate and then watch a movie at one of the multiplexes. This would cost a family of four at least Rs 1500, more than what 74 million households or 37.2 per cent of India's population earned in two months. The city was a paradox. People would come out to rally for the rights of pet animals, and others would brand their underage maidservants with a hot iron. It was a city where the malnutrition rate was 35 per cent,of schoolkids were overweight. For the Commonwealth Games, the homes of the poor were being dismantled. Leviathan billboards were being put up to eclipse slums so that foreign athletes would only be able to see glitzy shopping malls and departmental stores selling soy milk and broccoli.

There were two things Delhi didn't want: monkeys and poor people. Thousands of beggars were being bundled into municipal vans and there were negotiations with other states to take their beggars back. A few years earlier, the capital city had tried, in a similar manner, sending its monkeys to the wilderness of other states. And now, for the Games, hundreds of thousands of people would be displaced in all. In 2001, the sealing of small-scale factories in residential areas had rendered thousands of workers jobless. It was the ensuing unrest that the comrades wanted to take up as a cause, and motivate young labourers and workers to channel their anger into something 'meaningful'. To be close to such workers and win them over, the man had been living in the Molarband Extension colony.

Next page