You can tear down Lenins statue

Rip Marxist doctrine to shreds

Bury the history of revolution

Why just the statue?

You might as well chop Lenins corpse into pieces

And feed crows and vultures

It wont make a difference

O prosperous beings of the world

O capitalists

You who are driven by revenge and rejoice in bloodshed

We are countries. Give us autonomy.

We are nations. Give us liberation.

We are the people. Give us revolution.

Ahuti

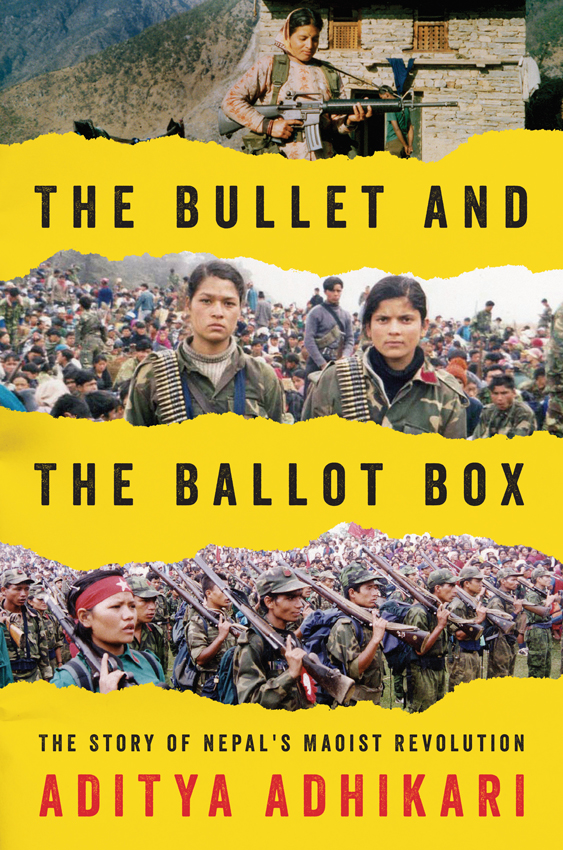

I n 1992, when these lines were published, Bishwa Bhakta Dulal, commonly known as Ahuti, was a member of the Unity Centre. This was a small communist party that would later split into two factions, one of which became the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist). Ahutis poem declared undying allegiance to an ideology that was widely thought to have been defeated. It was as though the poet were trying to smother his anxieties by sheer force of conviction. Ahuti eventually joined the faction that did not support armed struggle. But, four years after his poem came out, the rage and anguish felt by his comrades in the other faction erupted in an armed rebellion that altered the course of Nepali history.

Most leaders of the Maoist rebellion had come of age during the 1970s, when Nepal was ruled by an absolute monarch. King Mahendra Shah believed Nepal was not ready for democracy: he had seized power through a coup in 1960, banned all political parties and established what was called the Panchayat system. In Mahendras view, this was the only system that could protect and strengthen the nations independence and lead the country towards modernization. But the Panchayat regime allowed no room for political dissent, and its modernization programme reinforced rather than eliminated traditional social hierarchies. In such circumstances, it was natural that large numbers of young men and women who sought social and political change became drawn to communism.

In 1990, a popular movement led by a number of banned parties succeeded in bringing down the Panchayat regime. The Maoists, then scattered among various marginal factions, were ambivalent about this political gain. Many others, however, believed that Nepal had finally gained a system that matched both its citizens aspirations and the globally hegemonic paradigm of liberal democracy. The Nepali Congress, Nepals largest party, despite its sometime profession of socialism, had in practice always been committed to liberalism. The countrys two largest communist parties, duly chastened by the widespread liberal triumphalism, united to form the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified MarxistLeninist) (CPNUML), and pledged allegiance to the new parliamentary order.

With their firm commitment to revolution, the Maoists were thus swimming against a powerful tide. They not only rejected the parliamentary system, but also denounced despite Nepals heavy dependence on foreign countries imperialist and expansionist powers such as the United States and India. It was generally thought that no Nepalese government could survive without Indian support. A political group that was openly hostile towards India was not expected to go far. Both Nepali and foreign observers saw the Maoists as an irrelevant and faction-ridden groupuscule obsessed with an obsolete ideology.

But the Maoists remained undeterred. In February 1996 they declared their Peoples War by attacking several police posts in remote parts of the country. The government led by the Nepali Congress mobilized the police in response. Despite police reppression, the rebellion spread across the country over the next few years. The government declared a state of emergency and deployed the national army. In 2002, the king stepped forward to reclaim his power over the polity. All foreign powers with influence in Nepal India, China, the US and the UK backed the state against the Maoists, with the US alone providing over 20 million dollars in military aid.

In contrast, the Maoists had no external support. They initially relied on rudimentary weapons, and operated out of far-flung villages. Most of their cadre came from poor, rural backgrounds, and a significant section belonged to marginalized ethnic and caste groups. And yet, by 2005, the Maoists had gained control over most of Nepals countryside, and their rebellion had changed the face of the nation.

After a decade-long armed struggle, the Maoists finally signed a peace agreement with the mainstream parties that were opposed to the kings usurpation of power. Together they led a historic uprising that brought down the monarchy and paved the path for elections to a Constituent Assembly, one of the rebels key demands. The Maoists won around 40 per cent of seats in the Constituent Assembly. Other parties trailed far behind. The Maoists joined the government, and their political agenda came to dominate Nepals public debate.

However, when the Maoists launched the rebellion their ambition had been much grander: total state control. Now inside mainstream politics, they found themselves mired in a dysfunctional multiparty system, and were forced to compromise. Nonetheless, their growth as a political force had been extraordinary. Despite all the odds stacked against them, they became the only rebel group in the postCold War era to gain state power through Maos strategy of a protracted Peoples War. How was this possible?