Table of Contents

LALGARH AND

THE LEGEND OF

KISHANJI

Tales from Indias Maoist

Movement

SNIGDHENDU BHATTACHARYA

To

the people of Lalgarh,

the creators of this history.

Sometimes, reality is too complex

for oral communication.

But legend embodies it in a form

which enables it to spread

all over the world.

Jean-Luc Godard, Alphaville

CONTENTS

L algarh was the result of a long history of state neglect and Maoist mobilization. Bengals particular engagement with Maoist movements too has had a bearing on how the story unfolded. For background reading on how Lalgarh came to be, go to www.legendofkishanji.wixsite.com/lalgarh, where we have uploaded appendixes to the text.

Appendix I: Tashkent to Lalgarh via China and Naxalbari the story of the revival of the Naxalite movement in Bengal, seen in the context of the complex history of communist movement in India.

Appendix II: Maoism in India a timeline of the genesis and spread;Lalgarh a timeline, 1992-2011 and CPI (Maoist) central committee members, 200416.

Apart from the appendixes, we have also uploaded more photographs on the Maoist uprising in Lalgarh.

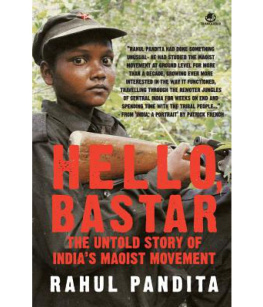

M eeting Maoist commander Kishanji in a liberated Lalgarh in 2009, and the experiences I encountered thereafter, became a turning point in my life as a journalist. It deeply influenced my understanding of not only Maoist politics but also the ways in which people react.

The meteoric rise and fall of the Lalgarh, for their corruption and suppression of voices of dissent. They blocked roads and gheraoed camps of security forces. The police were either locked inside their stations or forced to flee their camps. Panchayat offices were shut down. Hundreds joined hands to implement Maoist-guided local development initiatives. At night, members of armed militia stood guard in every village, often venturing out to mount attacks on CPM party offices and police camps.

Enthused by the developments in Lalgarh, the Maoist leadership called for creating thousands of Lalgarhs across the country.

I was lucky to be privy to many of the inner workings of the Maoists, even at the height of the conflict with the Harmad Bahini and the security forces. Most police officers, understandably, considered me pro-Maoist, if not their agent. But my office consistently stood by me, even in the most trying times.

In the three years between 2008 and 2011, I saw war, loss, justice, and the denial of it.

I witnessed a peoples court where Maoist militia leaders were about to execute a Harmad without the consensus of the villagers. I got picked up by paramilitary forces from a village, saw them pick up all the adult males of an entire village on the suspicion that some of them were Maoists. I spent nights at a villagers home that was razed to the ground a few days after I left. I spoke to Kishanji on the phone for hours, often every day, and often argued with him.

I heard hapless villagers curse the CPM and the police, but when the movement degenerated and was headed for a fall, I saw the same people feeling helpless because a section of the Maoist militia was metamorphosing into a new CPM. The very people who welcomed the Maoists with open arms, gave them food and shelter, started fearing the new leadership.

By the time the insurgency fizzled out after the alleged fake encounter killing of Kishanji on 24 November 2011, the Lalgarh experiment had become one of the bloodiest Naxalite uprisings in India.

A total of 355 civilians died at the hands of the Maoists within the jurisdiction of fifteen police stations in and around Lalgarh between November 2008 and November 2011, as did fifty-three security personnel. On the other hand, roughly eighty Maoists and their supporters died at the hands of the security forces and the CPMs Harmad Bahini. This is in addition to the deaths of 148 passengers in the Jnaneshwari Express tragedy the result of a horrific, multi-agency conspiracy and a fallout of the movement itself. The list is, however, far from complete. There are at least three dozen more civilians, both from the CPM and the Maoist camps, who remain missing even today.

At its height the Lalgarh movement had shed more blood than all other Maoist-insurgency-affected states put together. In 2010 the Maoists killed 478 civilians in nine states, of whom 180 were killed in and around Lalgarh (the Jangalmahal area) alone. In 2009 that number stood at 391, of which 134 were in Jangalmahal.

And, finally, the Lalgarh movement ended miserably, with delinquent guerrillas betraying their leader, Kishanji, to the security forces. These guerrillas were inducted into the police force and awarded a lump sum, as per the rehabilitation policy of the state government.

What gave this entire chapter its unique character was the charismatic albeit elusive persona of one of its central figures Kishanji. A member of the Maoist partys politburo and central military commission, he was also the spokesperson of the partys eastern regional bureau comprising Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Bengal and parts of Chhattisgarh. The Communist Party of India (Maoist) central committee called him a topmost representative of the post 1972 generations.

In Kishanjis words, The story of Lalgarh will be incomplete without the tale of the reorganization of the Naxalite movement after its 1972 setback. He did not get the time to elaborate on that, but, during the course of my research, I found out that Lalgarh would not have happened without the revival of the Naxalite movement in Bengal in the late 1990s and that the revival was a direct outcome of the progress of the movement in Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh (then part of Madhya Pradesh) and Bihar during the 1980s. Kishanji was the main link between these.

In Lalgarh, Kishanji consistently surprised everyone by using his cell phone to frequently interact with journalists and participate in live telephone conversations, on English, Bengali, Hindi and Telugu TV channels, with intellectuals, politicians and bureaucrats from across the country. The people of Bengal got to know more about Maoist politics during those few months than in the past few decades. Whether Kishanjis politics is right or wrong became a household debate.

Another chapter in Indian history the change of regime in Bengal after thirty-four uninterrupted years of Left Front rule unfolded simultaneously with Lalgarh.

The farmers movement against land acquisition for the Tata Nano plant in Singur

Kishanji received many a praise from the Maoists as the chief architect of the revival of Maoist movement in Bengal. It is also him who has been blamed the most for its collapse. His death exposed that CPI (Maoist) in West Bengal was virtually a one-man party, which many Maoists say should not have been the case.

The origin of Maoism can be traced back to 1928, the year when Mao Zedong first proposed the Protracted Peoples War (PPW) model of agrarian revolution for China, discarding the Soviet model of insurrection by the working class. The Communist Party of China formally accepted the line in 1935. The Communist Party of India (CPI) has followed the Soviet line right from its inception in 1920. However, the progress of the national liberation movement in China started drawing the attention of a section of Indian communists and Maos 1940 article, On New Democracy, got its first Indian edition in 1944. By 1948-49, CPI leadership in Andhra had started propagating the Chinese path, even though the central leadership of the party disapproved of it.