THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Limited, Toronto.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

This is a work of nonfiction. Nonetheless, some of the names of the individuals involved have been changed in order to disguise their identities. Any resulting resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

Names: Halford, Macy, author.

Title: My utmost : a devotional memoir / by Macy Halford.

Description: First Edition. | New York, NY : Alfred A. Knopf, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029736 (print) | LCCN 2016042547 (ebook) | ISBN 9780307957986 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780307957993 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Halford, Macy. | Christian biography. | Chambers, Oswald, 18741917. My utmost for His Highest. | Evangelicalism.

Classification: LCC BR 1725. H 1835 A 3 2017 (print) | LCC BR 1725. H 1835 (ebook) | DDC 270.092dc23

I

A river touches places of which its source knows nothing.

SEPTEMBER 6

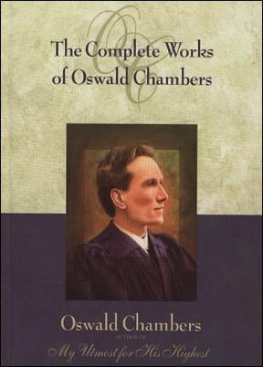

Dallas, 2011. The slender blue book had been lying on my bedside table for years before I started reading it, ever since the night of my baptism, when my grandmother had presented it to me as a gift, a sort of token of my entry into religious maturity. Id tried to read it then but hadnt gotten very far. At thirteen, I was a keen enough reader, and My Utmost for His Highest was an inviting booka daily devotional, with a brief reading for each day of the yearbut at the start it suffered unfairly from its association with a senior citizen. After one sentence, Id decided it was old-fashioned, as fusty and tedious as everything else my grandmother likedthe book equivalent of boiled vegetables, potted pansies, needlepoint, PBS, Chanel No. 5, and the taupe-colored Chevy shed been driving for twenty years. All of these things bored meI think they even bored my grandmother. If she liked them, it was because they were set to her frequency. Once, when I asked her why she never talked about her life, or anything, really, beyond the weather, she offered this as an explanation: The Macys are a very boring people, Macy being her maiden name and the source of my own. I replied that I hoped she wasnt including me in her assessment, and she smiled and said, Oh, no, Macy dear, you are always fascinating. It is tempting to read into this comment a slyness or even a bite, but my grandmothers was not a mind given to doubleness. On the rare occasions when she spoke of her own parents and grandparents, who had all lived out their lives back on the farm, she used the expression salt of the earth without irony.

But I shouldnt employ the past tense when I talk about my grandmother. She is still alive. It is merely her mindor much of it, anywaythat belongs to the past, having begun its final flight several years ago, around her eighty-sixth birthday. Otherwise, she is well and still going about her daily rounds as she always has, in the little red-brick house on Wabash Avenue, in Dallas, Texas, where in the 1980s and 90s she helped my mother to raise me and my brother and my sister, and which I leftto go north, to New Yorkjust after my eighteenth birthday.

It was a recent visit to this house and my grandmother that prompted me to begin thinking about Utmost, or rather to begin thinking about it in a different way than I usually did. At that point, Id been reading the book more or less every day for fifteen years, and so I thought about it often. Or maybe it makes more sense to say that I thought with it, since its presence in my life had become so fixed that I hardly noticed it was there anymore. It wasnt until this visit, when I happened to spot my grandmothers own ancient copy on the kitchen countertop, where we were sitting drinking coffee, that I began to wonder about the fact that wed both been reading it so long, she even longer than I, and even after losing her mind.

Do you still read this book, Nana? I asked, and, after Id repeated the question, she confirmed that she did. Every morning when I wake up, bright and early, she said. Six a.m. Thats when Im up. Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise. It was my grandmothers short-term memory that had disappeared, not her long, or (alas) the bit where her vast collection of moralizing aphorisms was stored. Also a woman, I replied. Just look at you! Ninety years old and still going strong, to which she shook her head in confusion, having apparently forgotten her previous statement. How, I wondered, could a person who couldnt recall what shed just said still enjoy reading? Wouldnt she have forgotten one sentence by the time she reached the next?

My grandmother took a sip of her coffee, then abruptly turned and left the kitchen. Shed gotten into the habit of disappearing like this, as if shed been called away by a voice only she could hear. I let her go, the way people are instructed to let sleepwalkers go, and while I waited for her to return I flipped Utmost open to the entry for the day: September 6. It was the entry about rivers, the one that contained the line A river touches places of which its source knows nothing. I smiled, both because the line was apt to the day and because Id been waiting for it to come around again, ever since the first hint of autumn had swept across New York. It was still high summertime in Texas, and it seemed strange to me to be reading the page on such a hot day, even though it must have been in the summer heat that I first encountered it. I read the words over again, trying to raise the temperature in my mind, but they refused to conjure anything but the crispness of impending fall in Manhattan, the coolness of the rivers that embraced the island. I seldom read the book out of order. Every evening, I opened it to the days reading, read through to the end, and wondered whether Id remember it 365 days later. Some entries, like the one for September 6, I always recalled very clearly, as if Id just read them; others were perpetually new, though Id read them eleven, twelve, thirteen times. I was never sure whether this was because they hadnt struck me as being memorable, or because Id changed so drastically in certain particulars over the course of the year that I was really reading them with new eyes. This possibility had been planted in my mind long ago, when I was a teenager. One Sunday, as I was sitting in a pew at church, reading my copy of Utmost and waiting for the service to start, a man had approached me and had begun to tell me why he found Oswalds book to be so compelling (Utmost readers tended to refer to its author by his first name only). Its a book that reads you, the man had said, rather than the other way around. Id regarded him coolly, noting the snakeskin sheen of his cowboy boots, the black twine of his bolo tie, the gel-slicked flop of gray atop his head. His comment struck me as a silly, unmanly thing to say, particularly for a man dressed as he was dressed, but over the years, as various of my Texas-born prejudices had fallen away, Id come to see the truth in it. It helped to explain why certain passages seemed to morph over time, and why people tended to read