Contents

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Hand, Richard J.

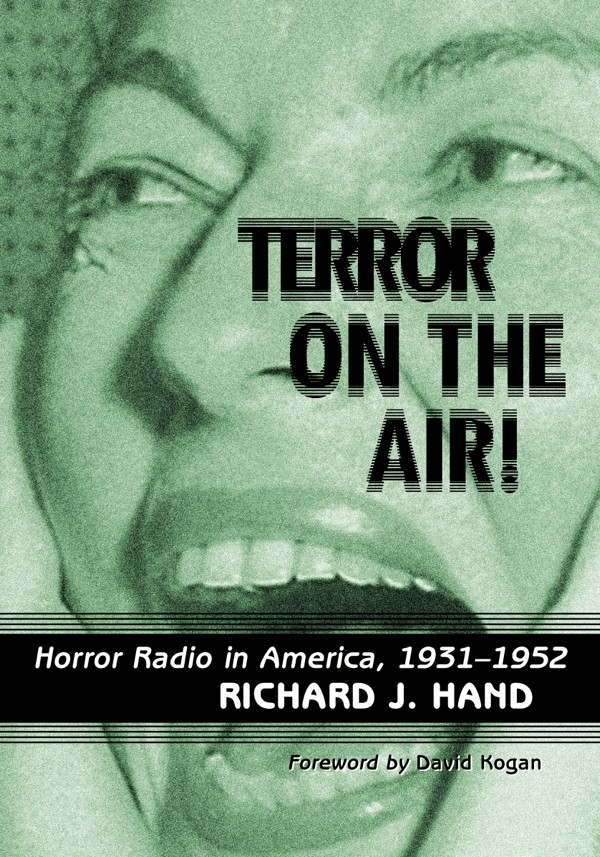

Terror on the air! : horror radio in America, 19311952 / Richard J. Hand ; with a foreword by David Kogan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7864-6919-2

1. Horror radio programsUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

PN1991.8.H66H36 2012

791.44'616409730904dc22 2005025351

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

2006 Richard J. Hand. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Agnes Moorehead in the 40s and 50s radio play Sorry, Wrong Number (Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Sadiyah, Shara and Danya,

who were always happy to listen with me...

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Board for a grant to support the research and completion of this book. A very special thank you is owed to David Kogan, one of the great writers in the history of radio drama, who read through some of my preliminary work with such enthusiasm and wrote the foreword to this book. To have David Kogans active involvement was a profound honor. This book exists thanks to the kindness and patience of some of the greatest authorities on old-time radio drama. In particular, I would like to thank Martin Grams, Jr., and David S. Siegel for reading through sample chapters and offering enlightening feedback. I would also like to thank some of the academic giants of radio studies: Professor Michele Hilmes (University of Wisconsin Madison), Dr. Frank Chorba (Washburn University) and Professor Andrew Crisell (University of Sunderland), who all greeted my research topic with advice and encouragement. Thanks, too, are due to old-time radio scholars and enthusiasts, especially Howard Blue and the custodians of the Quiet, Please website, who were supportive. A special thank you is owed to Mike and Ernestine Thomas, and to Don Dean, who were extremely generous in their support by providing invaluable information or materials. I would also like to thank Corey Klemow (director of the Sacred Fools Theater Company) and Michael Ross, son of the great Miriam Wolfe, for their helpful insights. I would like to thank Michael Henry and all the staff at the Library of American Broadcasting at the University of Maryland. Mike Henry and his colleagues are organized and knowledgeable and were invaluable in optimizing my time at the archives and instrumental in helping this book find its final shape. At the University of Glamorgan, I would like to thank my colleagues Mary Traynor (who, by the time this book reaches print, will have been a collaborator in the live reconstruction of old-time radio in the GTFM broadcast studios), Professor Mike Wilson, Professor Steve Blandford, Diana Brand, Sam Boardman-Jacobs, Katja Krebs and Daryl Perrins for listening to me get overexcited about old-time radio; Mike Davies and his colleagues at Media Resources at the University of Glamorgan for his invaluable assistance in assembling and processing the photographic images in this book; and my students who reconstructed live radio in the drama studio with such passion. Special thanks go to my mother for raising me to be a natural radio listener, and to Professor Don Rude, who sparked my interest in American old-time radio and steered me in the right direction. As ever and always, my love and gratitude go to Sadiyah, Shara and Danya.R.J.H.

Radio and the Power of Imagination:A Foreword by David Kogan

While audiences in theaters react to horror films with nervous laughter, tensing of bodies, and closing of eyes, there is always the comfort of the surrounding audience.

To listeners of a gripping radio play, particularly in a darkened room, the imagination can take oversometimes with dramatic consequences.

This was borne out on the night of October 30, 1938. It was on that memorable night that Orson Welles brought to the air his dramatization of H. G. Wells The War of the Worlds. As the program unfolded, it was interrupted by a series of realistic-sounding news announcements of a landing on Earth by a hostile invasion force of Martians armed with deadly ray guns. The invaders had landed in Grovers Mill, a small (fictional) New Jersey town, spreading death and destruction. During this broadcast, some of the millions listening panicked, believing they were hearing an actual news account of Martian invaders. Many New Jerseyites fled their homes, bringing about street riots and traffic jams. Phone calls swamped the police. It was mass hysteria. The panic kept spreading until officials of the network went on the air to explain to listeners that War of the Worlds was just a radio program.

Never was the power of radio to engage human imagination so evident.

I had been hooked on radio since I spent my savings on a crystal set in 1930. In the years of the Depression, radio was an escape for millions of people, and it magically transported people out of the darkness that surrounded them. War of the Worlds transported many listeners from darkness into panic. By that time, I was a freelance writer myself, writing for The Shadow, The Adventures of the Thin Man and Bulldog Drummond.

In 1940 I met Bob Arthur, and our first collaboration was The Mysterious Traveler, a series of thirty-minute dramas in the broad genre of mystery. The listeners would hear the eerie whistling of a train, then find themselves in the company of the regular hosta mysterious traveler on a trainwho would frame each self-contained story. We successfully pitched the idea to Mutual, who contracted us to write, produce and direct weekly scripts and also provide the cast. For their part, as well as broadcasting the show, Mutual would provide the studio, engineer, soundman, organist and announcer. In the subsequent nine years we produced some 450 scripts exploring genres such as horror, science fiction, suspense and fantasy. Mutual gave us complete freedom as to the themes and contents of our scripts, an almost unique privilege perhaps comparable only with Arch Oboler on Lights Out.

Bob and I would spend one day a week developing ideas, with me at a desk with pen and paper and Bob lying on a couch. When we had a complete story outline, either Bob or I would write the dialogue. I was always the director and Bob the producer. On the day of broadcast, the cast and I would gather around a table in the studio. We would read through the script. After this we would have a first-time read through on microphone, with myself and the engineer in the control booth. After this, there would be a second run-through with sound and music, with numerous pauses for level settings, sound balance and directorial notes on interpretation. After a short break, the announcer would arrive and we would do a complete dress rehearsal. Timing was critical at this stage: if the show ran over 29 minutes I would adjust the script accordingly.

We were always interested in the mail we received from listeners all over the country. We usually received a dozen to thirty letters a week, but some shows brought in hundreds of letters. We would do our best to read them and send off a reply. The letters about The Mysterious Traveler ranged from admiration to disbelief. Some inquisitive minds had queries on the plot, and there was considerable fan mail for the man behind the voice of the mysterious traveler, Maurice Tarplin.

Next page