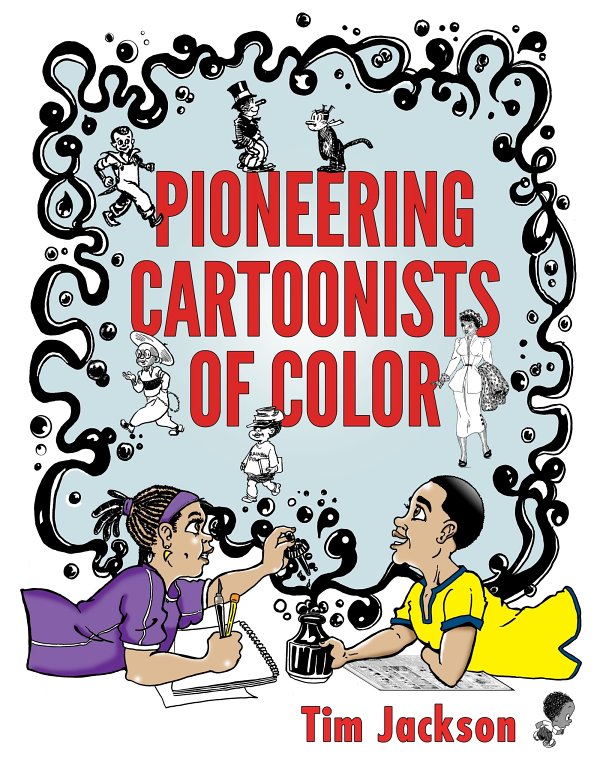

PIONEERING

CARTOONISTS

OF COLOR

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member

of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2016 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2016

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jackson, Tim, 1958 author.

Title: Pioneering cartoonists of color / Tim Jackson.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2016. |

Includes

index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015043952 (print) | LCCN 2015044595

(ebook) | ISBN

9781496804792 (hardback) | ISBN 9781496804853 (paper) |

ISBN 9781496804808

(ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Caricatures and cartoonsUnited States

History and criticism. | Caricatures and cartoonsSocial

aspectsUnited States. | African American cartoonists

Biography. | African American artistsBiography. | BISAC:

SOCIAL SCIENCE / Popular Culture. | LITERARY CRITICISM /

Comics & Graphic Novels. | SOCIAL SCIENCE /

Ethnic studies / African American Studies.

Classification: LCC PN6725 .J285 2016 (print) | LCC PN6725

(ebook) | DDC 741.5/973dc23

http://lccn.loc.gov/2015043952

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

In memory of

pioneering cartoonist

Morrie Turner,

mentor, friend, and

cheering section.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Cartoons in all their formsnewspaper comic strips, disposable comic books, the multiple stories in comic digests, Bazooka bubblegum wrappers, the back of cereal boxes, animated television programs, and even funny illustrations in advertisementshave been a lifelong fascination for me. Partly spurred on by my older brothers exceptional talent for drawing and painting, I set my focus on drawing comics, mimicking the ones that were featured on the comics page of the daily morning newspaper, the Dayton Journal Herald. I knew that I began drawing cartoons at age seven at the latest because of an illustration of jungle animals in formal dress, standing in line to enter a party. It was sent as a gift to my grandmother, and the date she wrote on it testifies to my age of seven at that time.

At a later stage in my development, I believed that I had come as far as I could on my own and needed to make a breakthrough into the broad world to improve my attempts at cartooning. I wanted to show my work outside of the family circle, whose members naturally loved anything I did. My father, although he insisted that I think about a more realistic career goal than drawing, just happened to bring reams of scrap paper home from his job where he worked as a janitor. The business-sized paper had the companys letterhead on one side, but there was still room to draw on it, as well as on the pristine blank reverse side. I got the ideaor more likely it was a now-forgotten suggestion by a teacherto write a letter with samples of my art to my favorite cartoonists to solicit advice. It never occurred to my youthful imagination that the people who drew those comic strips were not working away right there in the newspaper building downtown. Thats where I addressed the letters and somehow, after a month or two, the inquiries managed to reach the cartoonists; then responses came back in the mail. Among them were of course the Ohio cartoonists, including Milton Caniff, Tom Batuik, and Mike Peters. I recall at that time in my life feeling as if I were the only African American who wanted to draw cartoons, since all of the comics I encountered lacked characters with which I could identify (or even wanted to identify with because of the uncomfortable stereotypes of Blacks they embodied). Later in life, I learned that I was not the only Black cartoonist who felt this way. But there was one Black cartoonist most of us admired in common.

Rumor reached my ears that there was a new comic strip in the newspaper that included Black children, and those who saw it said it was called We Pals. For a time, I did not see it, since this comic appeared in the Dayton Daily News, the evening paper, and all the neighbors on our block only took the morning newspaper, the Dayton Journal Herald. Eventually, a friend supplied me with the comics page torn from the Dayton Daily News containing the elusive, much talked about, integrated comic strip titled Wee Pals by Morrie Turner, an African American cartoonist from Berkeley, California, who simply signed the comic Morrie. Much to my delight, Wee Pals went beyond the typical comics of the period, which regularly added one solitary Black character to an established cast. Wee Pals featured four distinguishably black individuals with faces that were free of scribbled lines to indicate skin color.

Over time, Morrie Turner became a catalyst in my growth as a cartoonist and one of two cartoonists who propelled me on to seek out information about the all-but-forgotten African American artists who illustrated for historic Black press newspapers and magazines that were simply unavailable in Dayton, Ohio. I would learn that there were also cartoonists who anonymously contributed illustrations and cartoons during the glory days of pulp comic books many, many decades before I ever picked up a pencil and developed aspirations to be a cartoonist and bring to the world my comic vision of featuring multiethnic characters expressing a worldview from my perspective.

Sometime around the age of fourteen, I began regular correspondence with Morrie Turner and took full advantage of the unique, impromptu cartooning education he offered by asking a multitude of questions about the various materials and techniques he used to create his comics. When his schedule allowed, he always answered with a handwritten letter with the cast of seven Wee Pals crowning the top of the stationary. Many of the cartoonists with whom I corresponded warned that I would have to abandon my dependence on the faithful old number 2 pencil and master the quill pen if I ever hoped to have my illustrations mass-produced. Morrie talked me over that creative hurdle by telling me about the kinds of pens he used to draw Wee Pals, and I popped open the Pringles Potato Chips can that served as my personal savings bank and hurried off to Ken McAllisters Art Supplies. There I purchased a set of Speedball nibs for drawing and calligraphy as well as a fine-point paintbrush and a bottle of Higgins India ink. Returning home, I commandeered the dining room table to studiously practice and literally relearn drawing cartoons using these new tools and make them succumb to my will, helping me draw an image that I felt proud enough to send off to Morrie for critique. Upon receiving his thumbs up, I set out to create comics and illustrations that I could reproduce on the nearest photocopy machine for sending off to the various cartoon syndicates and newspaper editors in the region.

From that point on, I fearlessly submitted my multicultural-themed, socially conscious comic ideas to a number of cartoon syndicateswithout success. But this did not deter me. I was convinced that the mainstream cartoon world still wasnt ready for a comic that directly confronted issues of race, blended families, bullying, self-image, sexuality awareness, and drug and alcohol use that I crafted into my newly developed comic strip, What Are Friends For? After being turned down by every syndicate to which I appealed, my job as a community organizer in Chicago gave me the idea to repackage the