Text copyright 2014 by Richard Gehr

All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

Published by Amazon Publishing, New York

www.apub.com

Amazon, the Amazon logo and Amazon Publishing are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

ISBN-10: 1477801154

ISBN-13: 9781477801154

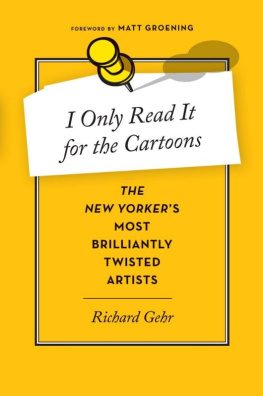

Cover design by Lynn Buckley

Author photograph Violet Gehr

For my parents

Contents

Foreword

View of The New Yorker from Portland, Oregon

I FELL IN LOVE with New Yorker cartoons before I could read. I remember being four years old, crawling on the carpet through the hovering living-room dust motes to the bookshelf behind my cartoonist dads easy chair. There a treasure trove of oversized hardback anthologies of magazine cartoons was kept conveniently on the bottom shelf, easy for me to grab and scribble in. With a mix of awe and bafflement, I pored through The New Yorker 19501955 Album; The New Yorker Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Album, 19251950; Helen E. Hokinsons The Ladies, God Bless Em!; James Thurbers Fables for Our Time and The Thurber Carnival; Charles Addamss Monster Rally, Addams and Evil, and Homebodies; Syd Hoffs Oops! Wrong Party!; and Peter Arnos Sizzling Platter, Hell of a Way to Run a Railroad, and Man in the Shower. Man in the Showers cover particularly unnerved methats the one with the hapless underwater naked guy gesticulating to his wife to open the shower door.

Throughout my childhood I returned to those cartoon books (along with memorable collections by Punch magazine contributors Ronald Searle and Rowland Emett), but learning to read the captions only wised me up slightly to the real meanings of these strange and beautiful and sometimes sexy drawings. In fourth grade my precocious pal Duncan Smith clued me in to the genius of Saul Steinberg, and we would sit in the adult art-book room at the Multnomah County Library in downtown Portland, Oregon, trying to copy Steinberg from his books The Passport and The Labyrinth. (Duncans illustrations were greatI couldnt draw a straight line.) I also spent countless hours in the basement at home among the piles of New Yorkers, never bothering with the long columns of snoozy print, only reading it for the cartoons. It wasnt until high school and college that I started digging the non-cartoon content, but the New Yorker thing I still remember most from those years is Steinbergs 1976 cover View of the World from 9th Avenue.

My grown-up love of New Yorker cartoons continues unabated. New Yorker cartoonists have always been fascinating creatures, toiling away in solitude and self-effacing about their subtle brilliance. I think I understand most of their cartoons these days, although I admit a few still bewilder me, which is enjoyable in its own perverse way. (That Ed Koren cartoon with the crashed carIts a narrative I didnt intendremains a stumper.) In 2004 I bought The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker (includes two CDs with all 68,647 cartoons ever published in the magazine), but the CDs were kind of balky. A couple of years later I got the eight-DVD Complete New Yorker, which proved even more annoying than the CDs; so I coughed up three hundred bucks for The Complete New Yorker Portable Hard Drive, which kind of worked until I lost it in a drawer someplace. And now here we are in the spectacular future and the whole New Yorker archive is online for subscribers... hooray!

My longtime friend and Boy Scout troop mate Richard Gehr has done a terrific job with the profiles in this book. He is possibly even more besotted with New Yorker cartoon mania than me, if the issues he packed on camping trips are any indication. His knowledge of the history and culture of the magazine and his incisive, revealing interviews make for great reading, and you can tell the cartoonists are tickled by his informed questions. New Yorker cartoonists, like almost all less exalted cartoonists, are a pretty unpresuming lot, but, man, are they quirky, sly, and funny. When Roz Chast, George Booth, Ed Koren, and all the rest read this book, I think they will be delightedas will you.

MATT GROENING

SANTA MONICA, CALIFORNIA

JANUARY 2014

Introduction

How to Read a New Yorker Cartoon

I F YOU THINK entering The New Yorkers weekly Caption Contest is a hoot, try competing with a roomful of cartoon fans and an open bar. A live version of the Cartoon Caption Contest is among the more popular events of the annual New Yorker Festival, and in 2012 I found myself sitting at one of several tables in Cond Nast Publications executive dining room, where participants enjoyed executive snacks and the opportunity to have their captions judged by the pros: George Booth, Harry Bliss, Kim Warp, and New Yorker editor-cartoonist Robert Mankoff. The tables competed against one another for copies of the recently published The Big New Yorker Book of Dogs. Not coincidentally, all three of the captionless images we were required to enhumor also involved canine situations. A captioning newbie, I quickly got the hang of this kartoon karaoke and was soon amusing myself, if no one else. (The one about Laika and the dating service was especially killer.) What is wrong with these people? I thought, as lesser efforts were rewarded.

The Caption Contest is an immensely popular feature. Some five thousand entries a week suggest that a good portion of the magazines readers imagine that they could step up to the plate and knock gags out of the park with these Yankees of Yucks. But, of course, thats only half the battle, insofar as relatively few of us can draw as well as quip. For much of the magazines run, outside writers supplied artists with their material. Today, however, drawing a New Yorker cartoon is rarely a two-person proposition.

In reality, cartooning for The New Yorker is mostly an exercise in rejection. Cartoon editor Mankoff and editor in chief David Remnick nix hundreds of cartoons for every one they publish in the magazine. One regular contributor, Matthew Diffee, has taken the iniquity in hand by publishing a series of Rejection Collection volumes devoted to Cartoons You Never Saw, and Never Will See, in The New Yorker. And when I asked staff writer Calvin Trillin for his thoughts on the state of New Yorker cartooning, he prefaced his response by saying it would be prejudiced by the fact that not a single one of his many cartoon ideas had ever made it into the magazine.

Two days after the festival, I was in Lawrence, Kansas, recounting my afternoon of shame to Jack Ziegler, one of The New Yorkers more inventive and frequently appearing cartoonists. I suppose I expected a little sympathy. Instead, Ziegler went about as straight-faced as Id seen him get all afternoon.

Now you know how I feel, he said.

But theres a lot more to a New Yorker cartoon than a clever caption, and it takes an artist like Ziegler to complete the equation. Like a pop single, every cartoon creates its own little universe in which you can linger. In fact, says single-panel virtuoso Dan Piraro, whose

Next page