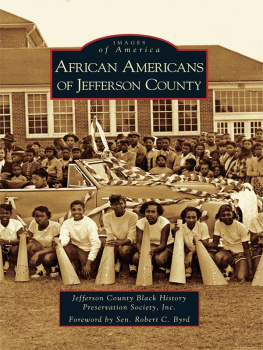

My Fathers Name

A Black Virginia Family after the Civil War

LAWRENCE P. JACKSON

The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London

LAWRENCE P. JACKSON is professor of English and African American studies at Emory University. He is the author of The Indignant Generation: A Narrative History of African American Writers and Critics, 19341960 and Ralph Ellison: Emergence of Genius.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2012 by Lawrence P. Jackson

All rights reserved. Published 2012.

Printed in the United States of America

Portions of appeared in an earlier version as The Will, Southern Quarterly (Summer 2009): 5787.

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-38949-3 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-38949-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-38950-9 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jackson, Lawrence Patrick.

My fathers name : a black Virginia family after the Civil War / Lawrence P. Jackson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-38949-3 (hardcover : alkaline paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-38949-9 (hardcover : alkaline paper)

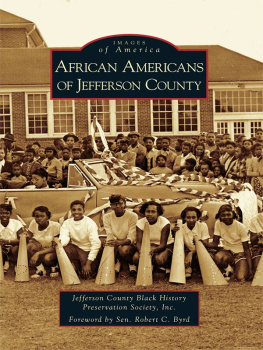

1. Jackson, Lawrence PatrickFamily. 2. African AmericansVirginiaBiography. 3. SlavesVirginiaPittsylvania CountyBiography. 4. FreedmenVirginiaPittsylvania CountyBiography. 5. Pittsylvania County (Va.)Biography. 6. ReconstructionVirginiaPittsylvania County. 7. United StatesSocial conditions18651918. I. Title.

F235.N4J33 2012

975.5041092dc23

[B] 2011034713

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This book is dedicated to my parents, Verna & Nathaniel Jackson Jr.; my brother, Greg Carr; my sons, Nathaniel & Mitchell; my grandparents, Christine & Vernon Mitchell & Virginia & Nathaniel Jackson

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project arose from my relationship with my father and my sons, and I am thankful to my ancestors for their immaculate guidance. Greg Carr gave me the spirited words I knew my father, and the work of David Bradley helped me to grasp the necessity of visiting children whose parents had been enslaved.

I am indebted to everyone who helped me to collect the research and who shared their time. Chanel Craft and Rev. Dan Ricketts provided valuable assistance to me in Pittsylvania. Lisa A. Lindsay generously gave me a place to stay in Chapel Hill.

In the fall of 2010, I benefited from the enthusiasm and candor of members of Freshman Seminar 190, Autobiography African American Style. In the spring of 2011, graduate students Anthony Cook, Yoshi Furuiki, George Gordon-Smith, and Diana Louis from the seminar Rewriting Agency in Slavery and Reconstruction in Southside Virginia read primary source documents, especially the US census, with deep insight. I would like to thank Emory librarian Erica Bruchko, who always enthusiastically answered questions and helped to find sources; Randall Burkett and the librarians at the Manuscript, Archives and Research Library at Emory University; Michael Page, the Emory GIS librarian who created the Pittsylvania County maps; Marie Hansen of Emorys interlibrary loan system; Kyle Fenton of Digital Curation; and Richard Luce, Vice Provost and Director of Libraries at Emory University.

Library professionals and scholars outside Atlanta were most considerate and include Naomi Nelson, Director of the Duke University Rare Books, Manuscripts and Special Collections Library, and her staff; the National Humanities Center, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, where the project was conceived (special thanks to Israel Gershoni, Jeff Kerr-Ritchie, and Tim Tyson); the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia; the Library of Virginia, Richmond; the Pittsylvania Historical Society, Chatham; the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond; historians Drew Swanson and Martha Katz-Hyman; and Pittsylvania County Clerk H. F. Haymore.

I thank Stephen Donadio and Douglass Chambers for publishing versions of this early work. Robert Devens of the University of Chicago Press, the presss anonymous readers, Robert Steptoe, Michael Elliott, Nathan McCall, and Delores Dwyer have all helped to make this a better book. I also thank Horace Porter, Arnold Rampersad, Houston Baker, James West, Keith Gilyard, Mark Anthony Neal, Al Yasha Williams, and my sister, Col. Lynn Jackson-Dorman of the US Army, for believing that this journey was important.

This book about the Old South was written in Richmond, Virginia; Durham, North Carolina; and Atlanta, Georgia.

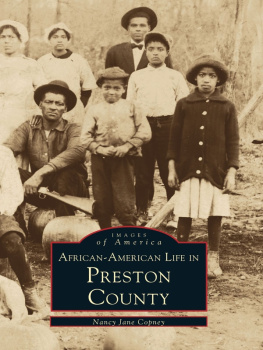

To Danville

When my wife and I learned that we were going to have a baby in the summer of 2004, we thought it would be fitting, if we had a boy, to name the child Nathaniel for my father and grandfather, and in honor of American patriot Nat Turner. Six weeks before the baby was due, I drove up to Danville, Virginia, in Pittsylvania County, the rural point of origin for the Nathaniels of my own family saga. More accurately, I drove just north of Danville to the outlying town of Blairs. I thought that walking the terrain of my forebears would put me in a paternal frame of mind and that, with luck, I might unearth my grandfathers old house by the railroad tracks. Now that I was on the verge of contributing to another generation that would carry that puzzlingly common surname for American blacksJacksonI was curious about how my fathers people saw the world. In the back of my mind, I wanted to better understand my father, such a formidable presence in my own memory.

My father, as an old Virginia saying goes, went back to Guinea in 1990, the year I finished college. Ours was a relationship filled with the anguished complexity of fathers and sons. I wanted to be like him, but never felt I could achieve his magnificent serenity. On the other hand, he desperately wanted me to build the emotional strength to be myself. By the end of his earthly life, my father and I had overcome the sore feelings and failed moments: I know that he loved me, and my love for him grows every day.

After he had gone, I tried different things to enhance my memories of him. On his birthday in 2001, I drove from Richmond, where I then lived, down Route 360 to Danville. I wanted to see the place where my grandfather had lived, which I hadnt been to since the last time my father had taken us there when I was seven years old. During that visit I had gone to the Danville tourist bureau and looked at telephone books from the 1960s and 1970s to see if I could find my grandfathers address. But I had forgott en a crucial fact: Grandpa Jackson had lived in Blairs, not nearby Danville, the comparatively robust city of fifty thousand on the Dan River. So I spent an hour in Danvilles colored cemetery, vainly looking for the headstone. I remember the trip mainly on account of pictures. Every ten miles or so on the route to and from Richmond, I stopped to shoot rolls of film, taking color photographs of every tin-roof barn and chinked wooden cabin that looked as if it, like my grandfather, had had its beginnings in the nineteenth century.

My father was not particularly close to his paternal family, so after my grandfather died in 1975 we visited Blairs only one more time, the next year. My final and most complete memory of the place is from that summer trip. Most of my time was spent sitting on my great-aunt Sallys front porch while the adults talked. My sister, who was eleven that summer, had been able to stay with a classmate in Baltimore, leaving me by myself. In the sweltering August heat I spent an hour alone on the porch and swatted about seventeen flies. I was just getting coordinated enough to swat a healthy fly, and the insects seemed to me the most no-account form of animal life I had encountered: uglier than ants, vicious and stubborn. Sometimes, while I was waiting for the adults and wishing for other kids, I would jog up and down the road outside the simple white clapboard house. In the living room, Aunt Sally had only hard candy in a bowl, and I remember moaning and pleading for a Popsicle.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).