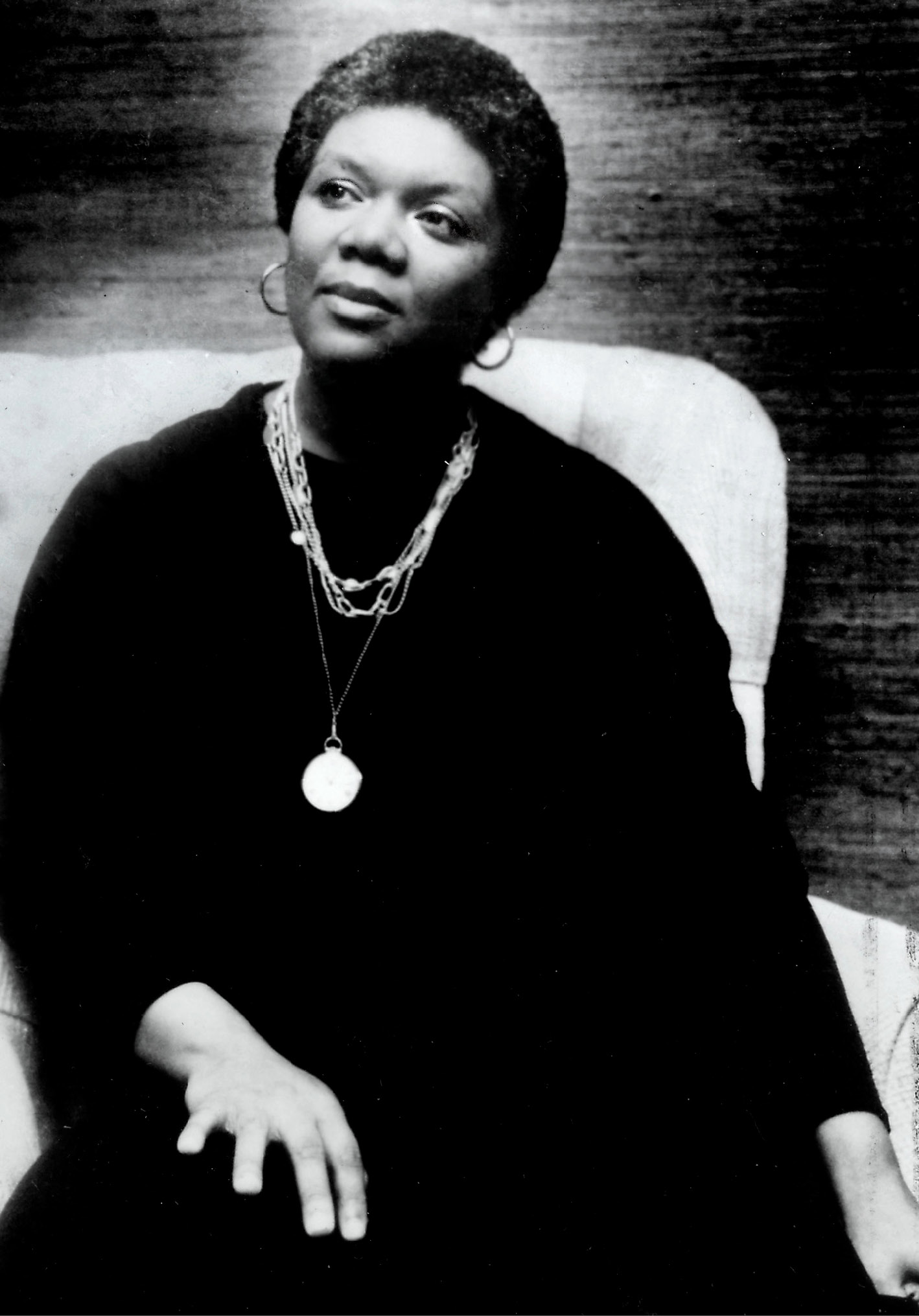

L ucille C lifton (19362010) was an American poet known for her work celebrating the African American female experience and family life. She is best known for her collections Good Times, Two-Headed Woman, Next, Good Woman, Blessing the Boats (winner of the National Book Award), and Quilting. The only author to have two books of poetry nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in the same year, she was awarded the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and the Robert Frost Medal for Lifetime Achievement from the Poetry Society of America. In addition to her poetry collections, Clifton also wrote numerous books for children, including her Everett Anderson series. Her literary legacy is being carried forward with the Clifton House, a writer and artist workshop space based in her beloved former home in Baltimore.

T racy K. S mith is a writer and former United States Poet Laureate. The author of a memoir, Ordinary Light, and four poetry collections, including Life on Mars, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2012, she currently serves as the chair of Princeton Universitys Lewis Center for the Arts.

GENERATIONS

A Memoir

LUCILLE CLIFTON

Introduction by

TRACY K. SMITH

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1976 by Lucille Clifton

Introduction copyright 2021 by Tracy K. Smith

All rights reserved.

First published as a New York Review Books Classic in 2021.

Cover image: Thornton Dial, Black and White, 2002; 2021 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo credit: Pitkin Studio/Art Resource, NY

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clifton, Lucille, 19362010, author.

Title: Generations: a memoir / by Lucille Clifton.

Description: New York: New York Review Books, [2021] | Series: New York Review Books

Identifiers: LCCN 2020058364 (print) | LCCN 2020058365 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681375878 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681375885 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Clifton, Lucille, 19362010. | African American poetsBiography. | Poets, American20th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3553.L45 Z46 2021 (print) | LCC PS3553.L45 (ebook) | DDC 811/.54dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020058364

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020058365

ISBN 978-1-68137-588-5

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

W hat is our relationship to history? Do we belong to it, or is it ours? Are we in it? Does it run through us, spilling out like water, or blood?

I think the answers to those questions, at least in America, depend upon who you areor rather, on who youve been taught to believe that you are. If the history you descend from has been mapped, adapted, mythologized, reenacted, and broadcast as though it is the central defining story of a continent, perhaps you can be forgiven (up to a point) for having succumbed to a collective distortion.

But what if yours is a history the wider world once recorded not as lives and feats but as articles of inventory? Men, women, children listed according to their age and value as property? What if the largeness of those liveswhat they endured, yes, but also what they carried, remembered, witnessed, and madehas been hushed up, negated, overwritten, or outright erased? What if the recovery of your full story sheds stark light on the lie of that other, louder story?

There it is: light. It took three paragraphs to creep in as a metaphor, though it runs through the work of Lucille Clifton like life force. Light comes to her. Light speaks. Light emanates from the figures of history and myth, like LuciferGods bringer of lightwhom Clifton claims as her namesake, and who in her rendering testifies:

illuminate i could

and so

illuminate i did

If light is what the work of Clifton is intent upon spreading, then Im tempted to think that history as we have been conditioned to accept it is unrefracted, all of a piece, and blindingly white. Whereas Cliftons imagination is prismatic; it slows down the central story so we can see what it is truly made of: all the dazzling colors moving at different frequencies and, depending upon circumstances, in distinct directions.

In Generations, her poetically terse and emotionally epic prose memoir first published in 1976, Clifton uses the occasion of her fathers funeral to attest to the lives lived and the marks made by the generations of people she descends from. First they are names, dates, and places. Like Caroline DonaldMammy Calineborn free among the Dahomey people in 1822 and died free in Bedford Virginia in 1910. To reinscribe these lives into recollected history is to restore history itself to a rightful state of commotion.

Once named, these kin arrive not singly but en masse, brought to life through the rhythm and inflection of voiceslike the voice of Cliftons own father, Sam Sayles, in whose vernacular rhythm Mammy Caline is not merely described but rather conjured:

Oh she was tall and skinny and walked straight as a soldier, Lue. Straight like somebody marching wherever she went. And she talked with a Oxford accent! I aint kidding. Dont let nobody tell you them old people was dumb. She talked like she was from London England and when we kids would be running and hooping and hollering all around she would come to the door and look straight at me and shake her finger and say Stop that Bedlam, mister, stop that Bedlam, I say. With a Oxford accent, Lue! She was a dark old skinny lady and she raised my Daddy and then raised me, least till I was eight years old when she died.

I hear, in Sayless Ohs and his Lues and his exclamations and his insistence, something that is not simply expressive but exultant andpositivelyoracular. He is engaged not simply in an act of telling but of creating and consecrating a capacity for belief and understanding in both his daughter andif we are listening properlyhis daughters readers. The passage above segues seamlessly into the following capacity-expanding moment, where Cliftons father signifies upon how, at eight years of age, Mammy Caline walked North from New Orleans to Virginia in 1830, at which point she was sold away from her family:

I remember everything she ever told me, cause you know when you that age you old enough to remember things. I remember everything she told me, Lue, even though she died when I was eight years old. And then I knowed about what she remembered cause thats how old she was when she got here. Eight years old.

Mammy Calines depth of feeling, knowledge, and lossin other words, the reality of her personhoodboth affirmed and was affirmed by the reality of young Sam Sayless selfhood. As a child in grief, he found depth of feeling and knowledge, or generated it, through belief in what Mammy Caline, in her own grief, would have been required to find or generate.

These are the lives that Americas dominant history, as defined by aspirational notions of white personhood, has let fall into shadow. These are the stories that have been left unmarked and untended by Americas preferred view of itself, like the graves of slaves on land passed down through the white generations. One of the major contributions of Cliftons writing is that she has teased out these lives, allowing them to demand their rightful space, to command our full attention, to teach us things about themselves and ourselves.