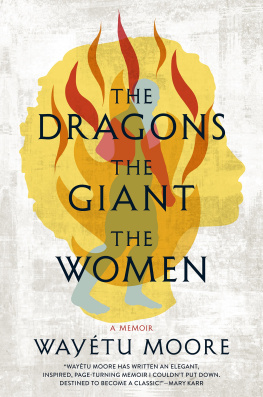

THE DRAGONS,

THE GIANT, THE WOMEN

ALSO BY WAYTU MOORE

She Would Be King

THE

DRAGONS,

THE

GIANT,

THE

WOMEN

A MEMOIR

WAYTU MOORE

GRAYWOLF PRESS

Copyright 2020 by Waytu Moore

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the Amazon Literary Partnership, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-64445-031-4

Ebook ISBN 978-1-64445-128-1

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2020

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019949911

Jacket design: Kimberly Glyder

Jacket art: Shutterstock

For Junior & David.

Whatever you are, I am.

Take your broken heart, make it into art.

CARRIE FISHER

AUTHORS NOTE

I have tried to recreate events, locales, and conversations from my memories of them. In order to maintain their anonymity, in some instances I have changed the names of individuals and places, and I may have changed some identifying characteristics and details such as physical properties, occupations, and places of residence.

RAINY

SEASON

ONE

Mam. I heard it again from another room, as I always did when the adults were careful not to mention her name around me, as if it was both a sacred thing and cause for punishment, and I ran toward it. Mam is what they called her then. Down hallways, across the yard, behind closed doorsher name the most timid kind of ghost. Mam so beautiful or Mam used to go there plenty or Thats not the way Mam cooked it they would say quietly, cautious not to raise the drapes with the wind of their voices. And I would stumble in, wanting to catch them in the act, to give me that word again for so long that I fell asleep to the sound of it. Startled by my tiny body, they would stop and ask if I had finished my lessons or if I wanted a snack.

Once when it was raining, I heard her voice outside. An Ol Ma, a grand-aunt maybe, told us that all of our dead and missing were resting peacefully in wandering clouds, and when it rains and you listen closely you can hear the things they forgot to tell you before leaving. Mam was not dead, they said, but I stumbled into the rain and stood beside the rosebush where I was sure I had heard her voice, full of laughter and long ago, singing those forgotten things.

Tell me where she is, I would ask.

In America, you girl. I told you. In New York, they would say.

Are you sure? I asked to be certain. When will we see her again?

Soon, they said.

Can I go there? I asked, though I knew the answer.

Why would you want to go there, you girl?

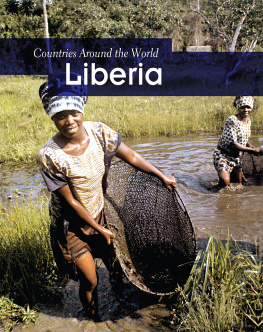

They convinced me that Liberias sweetness was incomparablemore than a ripe mangos strings hanging between my teeth after sucking the juice of every sticky bite, the Ol Mas milk candy that melted on my tongue, sugar bread, even Americanone a match for the taste then, of my country. This was all I knew of my home thenthat I lived in a place that made words sing, so sweet. Yet it was without my mother.

In those years, turning five years old tasted like Tang powder on the porch after supper. Little boys drove with their Ol Pas, a grandfather or other old man with pupils eclipsed with a dwelling blue, to the Atlantic, to fish facing the sunset. Little boys sat in parlors of opaque tobacco smoke as they watched Oppong Weah kick soccer balls into checkered nets against Chelsea. Little boys could now walk alone to those junction markets that sold everything from bushmeat to shoe-string, to buy the plantains and eggplant driven from Nimbas farms for their nagging Ol Mas.

Little girls could now help to wash sinks of collard greens in front of kitchen windows that faced pepper gardens. Little girls could draw water from neighborhood wells and balance them on their heads, full of braids and restless musings, all the way back to their houses as the sun lingered at the edge of the sky to make sure they had safe walks home.

I turned five that day and the greens felt soft between my hands. They only let me wash them once, and afterward I was pushed away and told to leave the cooking to the cooks.

You will have plenty time to wash greens, you girl, Korkor said, laughing from the hollow between the wide gap of her two front teeth.

But I want to wash them longer, I said.

She picked me up from the stool in front of the sink and carried me to a table where a cake tempted me from the middle of snack plates.

Look, you will spoil your fine dress! she said, straightening the purple linen.

The Ol Pa will be vexed if you spoil your fine dress, she rambled, and returned to the sink to complete the cleansing and preparation of my birthday greens. I did not believe that my grandfather would be angry with me if I spilled water from the greens on the dress he had sewn for my birthday. No, Charles Freeman would be proud that he would have one more granddaughter whom he could send for water from the well in Logan Town where he lived with Ol Ma.

It was a famous well, mentioned in many of Ol Mas stories about Mams childhood and those memories of her life before us. It was better than the well near their old home further inside Logan Town. Ol Pa was a tailor and Ol Ma was a shop owner then, and they had moved with other Vai people toward the city, where most settled in Logan Town after a man they call Tubman, the president at the time, gave jobs to rural Liberians. It was 1966.

They say the water well was a ground-level brick structure with concrete lining similar to most wells in Logan Town. It was a hand-drawn well with a bucket that dropped quickly in and out. As the bucket rose, Mam would grab the handle and pull it toward her small body to empty the water into her own plastic bucket. Once, alone in the yard, Mam peeked over the well and sang into it, as they say she always did, and the well threw an echo back up. Dance with me, she sang, and the well repeated her words, spitting a familiar voice onto the yard. She laughed, and while raising one of her hands to cover her mouth, Mam lost her balance and fell into the well. Darkness smothered her and the water below swallowed her body. The bucket rose and Mam spat the coldness out of her nose and mouth, gripped the rope, and yelled so that someone would hear her. As the bucket ascended, she heaved what she could out of her system and yelled again, scraping her fingers on the inside walls for something she could hold on to. The bucket fell again, and this time she did not know if she was moving or still, if the darkness was her end; the sunlight was so close and yet it mocked her in the distance. When the bucket resurfaced from the water, Mams grip on the rope loosened, and when she opened her mouth to yell, nothing came out. She stretched out her hands, expecting to scrape the concrete walls, to fall again and be lost forever in the Logan Town shadows, but instead, as the bucket rose she felt a coarse palm wrap around her right wrist. Her head lay limp on her shoulder as her body was raised out of the well. It was a Ghanaian neighbor, Mr. Kofi, whom Mam was known to taunt through her window as he walked to work every day. Thank you, Mam whimpered, barely conscious. From then on, Ol Pa made sure he sent at least two daughters or granddaughters to the well.