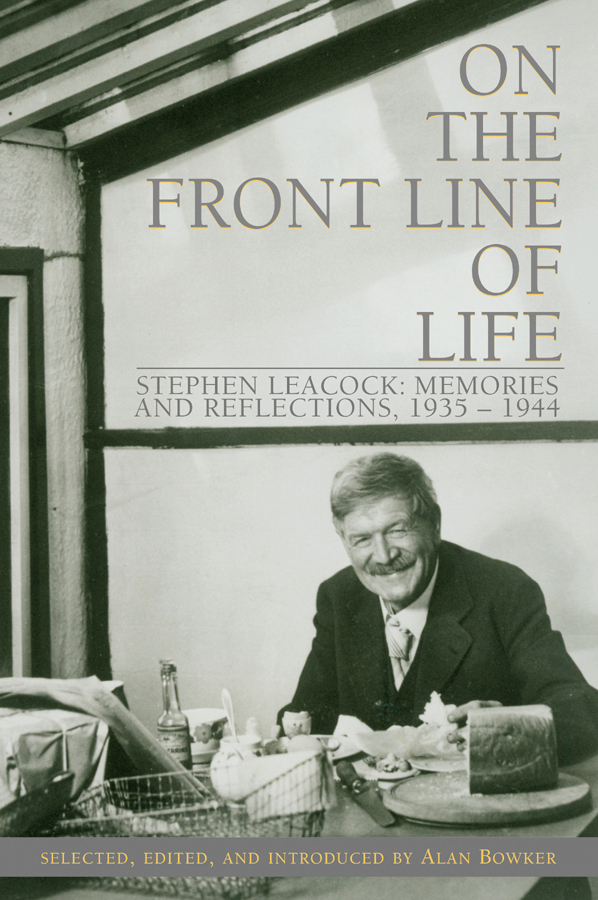

ON THE FRONT LINE OF LIFE

ON THE FRONT LINE OF LIFE

Stephen Leacock: Memories and Reflections, 1935 1944

Selected, Edited, and Introduced by Alan Bowker

Copyright Alan Bowker, 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Copy-Editor: Jennifer Bergeron

Design: Andrew Roberts

Printer: AGMV Marquis

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Leacock, Stephen, 1869-1944.

On the front line of life : Stephen Leacock : memories and reflections, 1935 1944 /

Stephen Leacock ; selected, edited and introduced by Alan Bowker.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-55002-521-X

I. Bowker, Alan, 1943- II. Title.

PS8523.E15A16 2004 C814.52 C2004-905472-4

1 2 3 4 5 08 07 06 05 04

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and The Association for the Export of Canadian Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program, and the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Printed and bound in Canada

Printed on recycled paper

www.dundurn.com

Dundurn Press

8 Market Street

Suite 200

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5E 1M6

Gazelle Book Services Limited

White Cross Mills

Hightown, Lancaster, England

LA1 4X5

Dundurn Press

2250 Military Road

Tonawanda, NY

U.S.A. 14150

ON THE FRONT LINE OF LIFE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

Stephen Leacock Jr. sat on the edge of his bed and began to read from his fathers essay. It was the winter of 1970. As a graduate student I had been trying for some time to meet him. At last I got the opportunity through the courtesy of the family who had taken him in as he tried to regain his health and reclaim his life. I do not remember their names, but they were immensely kind and I would have liked to know them better. The place was Ardtrea, Ontario, on Lake Couchiching. Stephen Jr. was dressed in pyjamas and a dressing gown, recovering but fragile in fact he died of a heart attack only a few years later. As a research exercise it was a disappointment. He was guarded and told me little I did not already know. The only piece of information I can recall after all these years was how devastated he had felt when he had asked his father what happened to people when they die, and his father had answered that nothing happens, they just cease to exist.

Then Stephen Jr. insisted on reading a passage of his fathers work, one that obviously held deep meaning for him, perhaps in his own attempt to come to grips with the Leacock legacy. It was part of a lecture entitled How Soon Can We Start the Next War, which Stephen Jr. had probably heard his father deliver many times when he accompanied him on a tour of Western Canada in 19367. Suddenly it seemed as though the son were conjuring from the past the voice and manner of Stephen Leacock as he warned isolationist North Americans about what another European war would mean:

Do not think that we can escape it here. Do not think that we can shelter ourselves behind the ocean and look upon this wreckage as destined only to blot the continent of Europe and never to matter to America. If it comes it will spread like a plague, driving across the continents with all the evil winds of disaster behind it. We are as much interested as they. Hodie mihi, cras tibi, so wrote the medieval monks on the stone coffins of their dead. Mine today, yours tomorrow. Your fate will be mine and your salvation shall be mine.

So we must plead unceasingly for an earnest sympathy with Europe, wiping out all the angers of the past, wiping out all the questions of whose are the honour and whose the guilt of the late war, remembering not the brutality, but only the bright pages of the heroism, the golden pages that open in either direction, pages that open as well for our so-called enemies as for ourselves. []

I tell you this: if the world is to be saved, that is the path of salvation in Europe. They may take it; they may not. The sky is heavy with a lurid light threatening to break from the clouds. There is the cool fresh air blowing above. Which can conquer? We dont know. You and I and all of us if we live a few years will know of wonderful happenings in the world, for the path has got to be made straight or the path will lead over the abyss. The problem cannot wait. It has grown too acute. The world has no time for bungling, or muddling through. That was good enough for the older civilization, but not for us now.

I had read all of Leacocks books, some many times. Why had this passage never caught my eye? Because it is buried in a lecture that contains mostly foolish stuff, warmed-over satire about European diplomacy, jokes, and funny stories a lecture Leacock had used to entertain dozens of audiences and thousands of people. But now I could imagine the electric effect of this funnyman suddenly turning serious and delivering this heartfelt message.

A quarter-century later the memory of that evening at Ardtrea came back to me when I was asked to add a postscript to my introduction to Stephen Leacocks Social Criticism, which was being republished after twenty-two years. I had been long away from academe, pursuing another career. Now I found that new research and the passage of time had altered opinions about Leacock and his work. Some of what had once been thought funny and topical was now considered dated, as were many of his ideas and opinions. But as I took a fresh look at his essays written in the 1930s and 1940s, I saw again what Stephen Jr. had shown me: there was a great deal of fine writing here that deserved to be presented to modern readers.

Scholars had found much of Leacocks late work repetitive and of poor quality. They had attributed this to writing too quickly, for money. But this was only partly true. Leacock wrote funny pieces for money, but he was also very generous with his pen when he thought the cause worthy or the subject interesting. Sometimes Leacock seemed obsessed with the idea that he was writing against time in response to an urgent public need for what he had to say. He would have been puzzled by criticism of his self-plagiarism (whatever that means). He was a public figure whose views were frequently sought, and there was a steady demand for his humour. He gave the same lectures time after time, and no one complained about that. Why should he not rework good material when it was likely that his readers would not have previously encountered it? Surely what was important was that the material was good in the first place.