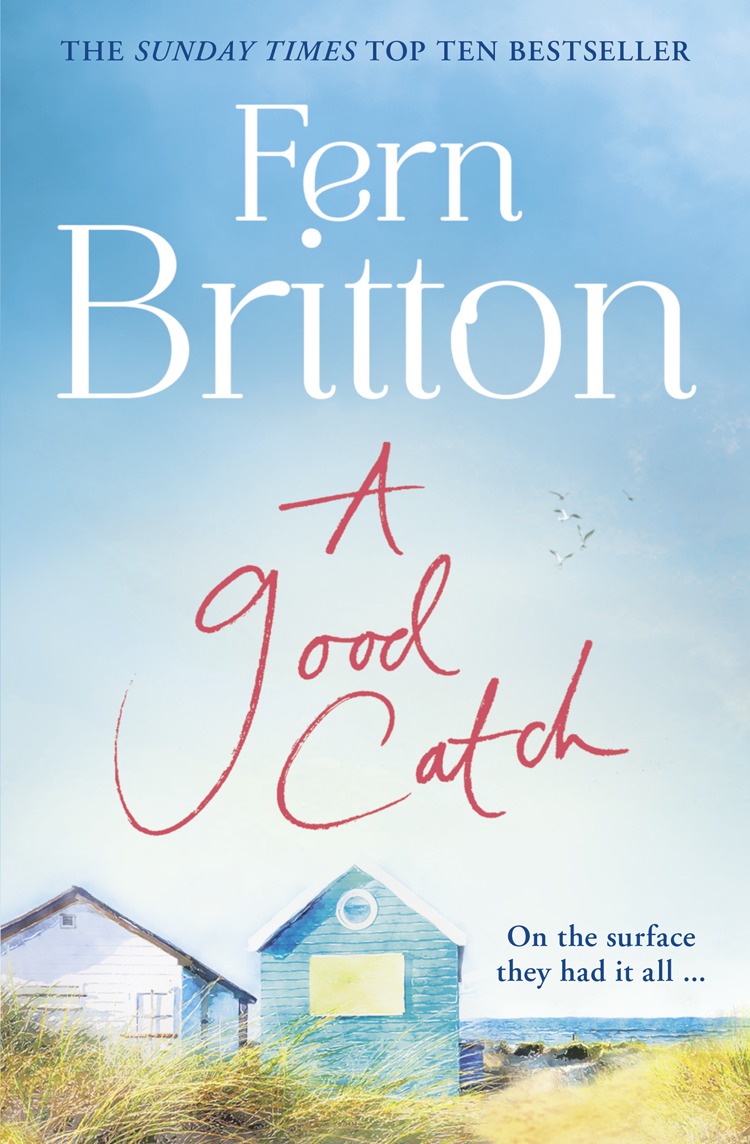

To my darling Goose.

Thank you for making me laugh so much.

Love you, Mum.

G reer Behenna had never felt so drained. Relieved to be alone at last, she closed her front door and leant her head on its cool, solid wood.

The inquest had been conducted with meticulous precision. The courtroom, even with its lights on, couldnt pierce the gloom of the winters day hanging outside its windows. The warmth from the old-fashioned radiators filled the air, right up to the high and corniced ceiling, with a density of heat that had left Greer drowsy and with the beginnings of a headache. She had listened to all that the witnesses had said and heard none of it. When called to the stand she gave her own evidence, but remembered little of it now.

So separated were her mind and body she almost floated up the stairs and into her room, where she pulled off her black Armani dress and carefully hung it up in the wardrobe. She found her jeans and a warm jumper and put them on. In the kitchen she filled the kettle. Tom was outside, sitting on the windowsill and mewing crossly. As soon as he saw her he jumped down and clattered in through the cat flap. She fed him. The kettle boiled and she wondered what shed put it on for. She couldnt face another cup of tea that day. She went to the fridge but there was no wine. Shed drunk the last of it the previous night. She drifted through into the drawing room and then the dining room, where theyd had so many family celebrations. Back in the drawing room, she reached for the remote control. The television came to life with a rather camp man talking about antiques; she switched the TV off again. Restlessly she got her coat and warm boots from the boot room, picked up her keys from the console table in the hall and left Tide House for the only place that felt right: the cove.

Greer had found herself seeking the solace of the cove more and more of late. The tide was out and she walked down to the waters edge. She found a patch of smooth rock to sit on that was otherwise covered in mussels. She closed her eyes and breathed in the scent of ocean and seaweed. She saw him in her minds eye. He was standing in the surf, casting his line to catch the sea bass that were lurking beneath the waves. His back was to her but she knew that hed be frowning slightly, concentrating on the fish, his fingers feeling for a bite on the line. She watched him turn round and, when she saw his face, it wasnt the man that she saw, but the boy. His blond hair, almost white from the heat of summer, plastered around his face, his eyes the colour of the sea, looking at her coolly with that familiar mix of curiosity and indifference. Remembering his face as it was then, Greer was suddenly taken back to the long hot summer of 1975, when she was almost five, and she first saw Jesse Behenna

*

He was sitting on Trevay quay, loading a crab line with a mackerel head. His tousled blond head was bent closely to the task and, when he was happy that the bait was secure on the hook, he swung the line to and fro before dropping it into the deep, oily water.

He drummed his dangling feet over the slimy sea wall in concentration. For a few seconds he watched the line sink to the bottom. Satisfied that it had, he shifted his face to the horizon and screwed up his eyes, as if hoping to bring into focus something that he couldnt see. He rubbed the back of his hand across his nostrils and then turned his attention to a bucket by his side.

Ere you go, lads, he said, putting a hand into the bag of chips by his side before dropping one into the bucket. Greer saw the quick scuttle of pincers through the opaque of the plastic.

Move up, Greer. Her mother, Elizabeth, sat down next to her on the sun-warmed, sea-roughened wooden bench, checking for seagull mess. Your dads just bringing the ice creams. Dont get any on your dress.

Can I do some crabbing?

Greers mother looked almost offended. Whatever for?

It looks fun.

Her father sauntered up, carrying three dripping 99s. Ere you go, my beauties.

Can I have a go at crabbing, Daddy?

He looked at her sideways. What does your mother say?

I say shes in her best dress and I have quite enough laundry to do, said her mother.

She can take it off, replied her father, Bryn, winking at Greer. Lovely day like today. He ignored his wifes horrified stare. Eat up your ice cream and well nip to the shop and get you a crab line.

And a fish head.

Yeah, and a fish head.

And a bucket.

Of course, cant go crabbing without a bucket.

The sun was warm on her bare shoulders as she sat, in just her vest and pants, on the gritty, granite sea wall, just a few feet from the boy. She dangled her legs, thrillingly and dangerously, over the sea wall, just as the boy was doing.

She had seen him pull in several crabs and drop them in his bucket and was desperate for the same success.

Right. There you go. Mind that hook, its sharp. Her father passed her the baited line.

She looked at the lump of fish stabbed through with the large hook and nodded solemnly. I will, Daddy.

Do you want me to show you how to feed the line out?

I can do it.

Well, keep it close to the wall. The crabs like it in the dark. The tides comin in so theyll be washed in with it. Tis no good crabbing on an outgoing tide.

Greer was getting impatient. All the crabs would be in that boys bucket if she didnt hurry up.

Let me do it, Daddy.

She took the square plastic reel from her father and slowly let the line out. She leant her head as far forward over the edge of the wall as she dared.

Its landed, Daddy.

Good girl. Now sit on the reel and it wont fall in. If you lose it, I aint buying you another.

She lifted her thigh, already growing pink from the sun, and wedged the sharp plastic of the reel firmly under her buttock.

Can I pull it up now?

Give it a couple of minutes.

She looked over at the boy who was again wrinkling his eyes and staring at the horizon. Her father surprised her by talking to him. Ello. Youre young Jesse Behenna, arent you?