Copyright 2009 and 2010 by Mark Christensen

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except for use of excerpts in book reviews, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

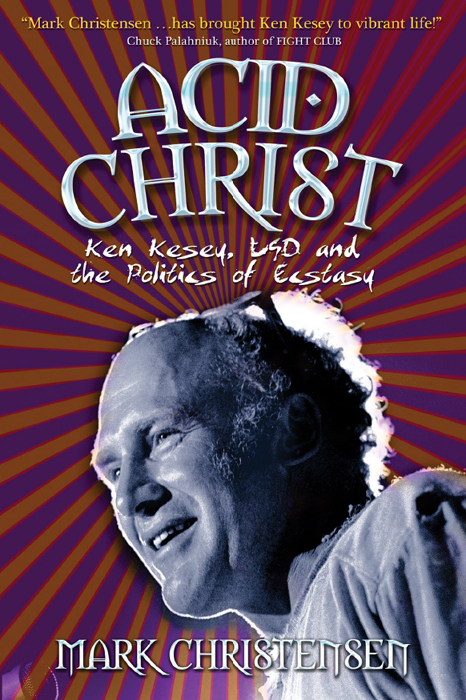

Cover design: Jake Kiehle

Cover and interior photographs: Clyde Keller

Author photo on back cover: Clyde Keller

Author photo inside back cover: Greg Steiger

Book layout and design; jacket layout: Darci Slaten

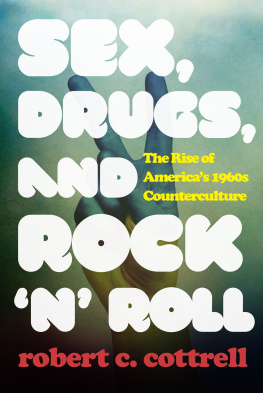

Sections of this book have been previously published in different form and have appeared in Rolling Stone, Penthouse, High Times and Oregon Times.

For information regarding sources and copyrighted material used in this book, contact Schaffner Press, Inc.

This is a First Edition

Printed in the United States

2010

Schaffner Press, Inc. PO Box 41567 Tucson, AZ 85717

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Christensen, Mark.

Acid Christ : Ken Kesey, LSD and the politics of ecstasy / Mark Christensen. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-936182-00-8

ISBN-10: 1-936182-00-9

1. Kesey, Ken. 2. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. I. Title.

PS3561.E667Z64 2010

813.54dc22

[B]

2009036336

This book is a work of independent commentary and criticism about the life, times and work of a noteworthy and influential American author. It is not an authorized or definitive biography of Ken Kesey, and it is not endorsed by or affiliated with the Kesey family or any of the authors sources. Rather, the author provides a narrative that draws on both primary and secondary sources but reflects his own critical judgments. Every attempt has been made to identify and cite the original source materials that are quoted in the book. All such sources are used either with permission or pursuant to the Fair Use Doctrine. For further information on sources, see the acknowledgments and endnotes at the back of the book.

For Deb, Katie and Matt,

and in memory of David Kelly

P ROLOGUE:

N EON RENAISSANCE MAN

When youve got something like weve got you cant just sit on it and possess it, youve got to move off it and give it to other people. It only works if you bring other people into it.

Ken KESey

O ld enough to have bought weed when most of it probably was, I grew up around the Kesey Chautauqua, whose personnel were space lumberjack demi-gods of literature and chaos, less actual than imagined, andnot too cosmopolitan. I first met the corporeal Kesey when my heroes were pretty much limited to John Reed, Rick Griffin, Fred Exley, the Byrds, Herman Kahn, Erma Bombeck, Rabbit Angstrom and the Midnight Rambler. I was puzzled. Who was he? The Kesey I remembered was healthy, almost big, but stood out because of the neon glow of his celebrity more than anything else.

As a college kid circa 1970, I expected Kesey to produce, in a book as thick as the Bible or a brick, what I, like the rest of my generation could not come up with on our own: The Answer. The problem: Kesey stood for community, not plans. (Since we dont know where were going we have to stick together in case someone gets there.) One did not freak freely according to a plan. So what then I wondered wasthe gestalt?

Later, at age 27 Id seen partial early drafts of Sometimes a Great Notion at the University of Oregon library. Keseyd written three versions of key sections of the bookeach seeming better than the lastat a time when Idve given anything but my life to write one great version of anything. But when I met him, he seemed about as literary as Bronco Nagurskihe had the unassuming hyper-gregarious, kick-ass style of a frat boy turned hippie farmer turned high school football coach turned psychedelic Chevie salesman (he was promoting his Poetic Hoo-Haw arts festival at the time), an aw-shucks demi-god who did day labor during the height of his fame, or at least claimed to. By then, living-in-the-NOW Kesey had abandoned the novel, tired of the novelists chore as a stagehand, having to supply the sun, moon, stars, chairs, tables, sofas, guns, Kleenex, fried chicken and femme fatales essential to the paper illusion, deciding: why not just, with a movie camera, be the story yourself?

Keseys personal dramatis personae, his famous posse The Merry Pranksters, were soon revealed to me as a cross between a cult and a twenty-year-long fraternity party, at the helm of which Keseypsychedelic Americas leading figure of freedom and funreigned kingly as a clockwork control freak, a man who was much enamored of occult theories of history and who was said to plot the dreams and fates of those around him as adroitly as any good novelist ever plotted an imaginary cast of characters.

I was impressed. Friendlier to fame than fortune, Kesey had existed for me as a sort of medieval rustic monarch of the counterculture whose castle just happened to begiven the utopian rural ideal he championeda barn, essentially a kids fun housea home fit more for Captain Kangaroo than William Faulkner.

But werent groundbreaking novelists Zen-placid stone Buddhas who created and controlled a divinely revelatory universe? And werent genius control freaks supposed to be in control of not only others but, well, themselves? For despite his commanding presence, after being around him for a while, Kesey didnt actually appear to be in control of much of anything. In fact, in ways he seemed like a great big kid. Energetic, jokey, always moving. He looked more like he was just making himself up as he went along.

But, given his awesome boy wonder bonafides, could that possibly be true?

As an alumnus of the University of Paul Krassner, who lived by his texts when I was in college, I had first intended to write the tale of how Krassners patriotically seditious broadsheet The Realist was the core of Vietnam era social protest and how, as a relentless fashion critic of the emperors new clothes, he scripted the yellow brick road map for cultural change in the 1960s, saved the Republic from corporate techno-fascism and provided the pivot around which all news media changed.

My idea: almost everything you think, feel, know or believe comes not from the Bible, science, Socrates, Avicenna, Descartes, Kant, Rousseau, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche or Tony Robbins but from the woefully under-recognized (that is to say sadly under-worshipped) Krassner. An early writer for Mad and Playboy who took elements from both, combined them with a brilliant libertarian political sensibility and a love of conspiracy theories, Krassner inspired the playbook for the Love Generations 1960s Street Fighting Menwhich had more to do with returning to the ideals of the American Revolution than achieving satori or killing your parents or your TV set.

A visionarys visionary (Krassner published his friend Lenny Bruces obituary two years before Bruce died), a guru to the gurushe had the ear of both Bob Dylan and John Lennon (and, on occasion, Lennons wallet as wellJohn there in a pinch to underwrite The Realists printing bill). The Realist was among the most inclusive, scary and funny catalogues of a world going haywire ever published. Krassners formula combined investigative reporting with satire to create the template for everything from Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher