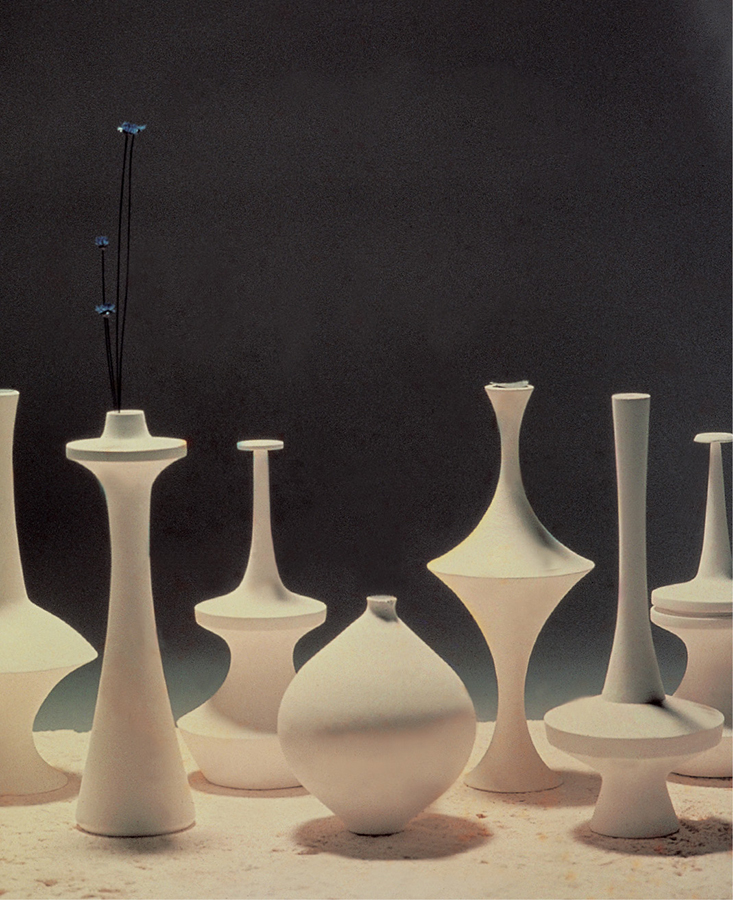

Pure, unadulterated beauty should be the goal of civilization.

Rowena Reed Kostellow

ALSO AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES:

D.I.Y. Design It Yourself , by Ellen Lupton Form+Code , by Reas, McWilliams, & LUST

Geometry of Design, rev. ed. , by Kimberly Elam

Graphic Design Theory , by Helen Armstrong

Graphic Design Thinking, by Ellen Lupton

Grid Systems , by Kimberly Elam

Indie Publishing , by Ellen Lupton

Lettering & Type , by Bruce Willen and Nolen Strals

Thinking with Type, rev. ed. , by Ellen Lupton

Typographic Systems , by Kimberly Elam

Visual Grammar , by Christian Leborg

The Wayfinding Handbook , by David Gibson

CONTENTS

PAOLA ANTONELLI

Curator of Architecture and Design,

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

PURE, UNADULTERATED AMERICAN BEAUTY

After decades of ideological suspicion, we at last feel again comfortable using the b word. It is a different kind of beauty, which has become human and immanent and is acknowledged to be in the eyes of billions of beholders. Pasionaria Rowena Kostellows motto, which reinforces the supreme principle of beauty with attributes such as pure and unadulterated and contemplates it as a responsibility to people, carries the echo of a social mission that is centuries old. In her philosophy, beauty was a superior state to be attained through strenuous practice and progressive shedding of impurities, which could be attained only by the few privileged individuals who could devote their lives to it. Studying Ms. Kostellows work is akin to taking a plunge into a different ancient time, when the elites task was to produce beauty and then make it available to the masses.

The lucidity, both intellectual and formal, of her principle highlights a quintessential characteristic of American design. American design, like much of American culture, perennially oscillates between populism and elitism, between the revolutionary beauty and availability of Tupperware and the elusive exclusivity of Marcel Breuers furniture. Both extremes express design excellence, in the design of the brand or the detailed perfection of one item. The long path toward a true American design has reflected this dichotomy, a by-product of the countrys powerful class system.

Postmodern thinkers like Jaques Derrida, Betsey Johnson, and Pedro Almodvar have taught us that beauty is all in the intention, the novelty, the composition, and the attitude, certainly not in such a reductive concept as formal homogeneity. The emancipation from the old-fashioned concept of absolute beauty is one of the greatest achievements of this century. The ideal of style democracy is a recurring theme in architecture and design.

Beauty today is a matter of composition and personality, in urban fashion, design, and architecture alike. Hip-hop music, based as it is on sampling and composing new and pre-existing tracks and giving them a finishing varnish of surprising novelty, is the paradigm recipe for contemporary beauty. It is based on synthesis and individual talent. Like music, fashion is a successful manifestation of democratic individualism in an end result called style. Fashion demonstrates that beauty coincides today with the affirmation of personal taste and that individuals can and have been upgraded to the role of authors and sole arbiters.

Yet in the early 1800s, America was still psychologically a European colony that strove to emulate the refinement of the European aristocracy. Furniture for the wealthy was generally imported. The middle class longed for the same ideal of luxury and style, and bought imitations. The nineteenth-century Shakers provided one of the first examples of original American modern design. Their furnishings and interior architecture display a sobriety and honesty that are a direct portrayal of the circumstances that generated them. Materials were used in harmony with their capabilities, which American design historian Arthur Pulos calls the principle of beauty as the natural by-product of functional refinement, a principle many use now to define goodness in design.

After Henry Fords emblematic Model T experiment of the 1920s, the American 1950s came closest to this ideal. Those were the years when resources from the idle war industry were converted to civilian and domestic use by such great designers as Charles and Ray Eames and anonymous engineers to provide the booming middle class with a brand-new, clean, efficient and especially affordable world.

The East Coast architectural aristocracy, led by The Museum of Modern Art and Harvard University, had platonically embraced the visions of modernist migrs Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. The new architecture and design for modern living coming from the West and the Midwest were about practice, not theory, and were born out of economy. They were symbols of American sensibility and idealism.

Ms. Kostellow still studied the divine, absolute, and Nietzschean kind of beauty of European modernism. The European modernist ideal, she realized, no longer existed as an import and needed to be translated and assimilated into New World culture. During her passionate career as an educator, an aware first step in this longer democratic process, she gave her students a clear idea of the sublime and a path to achieve it. She empowered them toward future choices, to enrich a quintessentially American culture, and to free it from its European chains.

EMILIO AMBASZ

architect and designer

former Curator of Architecture and Design,

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

It is deeply regrettable I never had the pleasure of meeting Ms. Rowena Reed Kostellow, but from reading her former students statements, I know that she must have been a most beguiling teacher. I would dare to call her a pedagogical seducer. It is obvious that she received every students idea with great respect for the kernel of imagination it might have contained and made it bloom. She was both earth and rain.

I can imagine her observing a students timid proposal, gleaning the chaff from the wheat, and inviting him to participate in that magical process whereby she turned that seed into the plant it might become. She taught by example. Shamans also teach that way.

Industrial design is an intellectual profession. In less label-oriented times, it would have been called a mtier of arts and crafts, its ultimate product an artifact. It was one of her many gifts to never allow her students to forget that their apostolate is to be functional-form givers, to engage an act of creation that has to encompass both pragmatic and emotional considerations. One of the rigors that she taught was that meeting the operational requirements of a new product is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for its adopting a meaningful identity. The product has to represent a formal embodiment of spirit and intelligence; it has not only to talk to the mind but also to touch the heart. Else it would be a lifeless instrument, just useful to accomplish a purpose, but arid and without contribution to a well-rounded life.

Her manner of teaching, creating in front of the students, was not used to dazzle them, although I suspect that when she could dazzle herself, she felt uplifted. A through and through teacher, she did not hide the fact that the act of creation is a lonely, frightening jump. The student has to jump alone, even if his/her hand is held until the last moment. But she taught them also that one could train for such a jump and revealed to them the mental processes she went through to arrive at her questions and suggestions. Eminently, she was concerned with bestowing a method upon each student to reduce seemingly disconnected problems into a systematic organization of relationships. In essence, she never forgot that method comes from that Greek word methodos (the way).

Next page

![Ethan Ham [Ethan Ham] - Tabletop Game Design for Video Game Designers](/uploads/posts/book/119417/thumbs/ethan-ham-ethan-ham-tabletop-game-design-for.jpg)