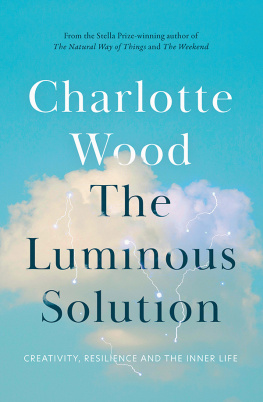

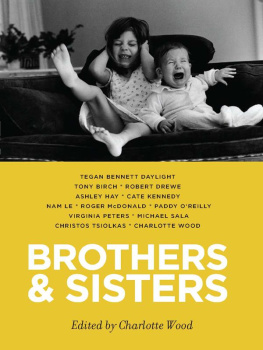

THANKS TO those who helped me write this book, often without knowing it: Rebecca Hazel, Alison and Mary Manning, Ruby and Lily Johnson, Jane Doepel, Kerry and Deborah Bennett, the Bundanon Trust, David Whish-Wilson and Curtin University, Joan London, Eileen Naseby, Lucinda Holdforth, Vicki Hastrich, Tegan Bennett Daylight, Ailsa Piper, Caroline Baum, Hannie Rayson, Dorottya Fabian, Anne Brewster, Stephanie Bishop. I thank all the writers who generously took part in The Writers Room Interviews; each conversation has influenced my work in profound ways. Thank you to Jenny Darling, Jane Palfreyman, Ali Lavau, Siobhan Cantrill, Clara Finlay, Lisa White and all at Allen & Unwin for their expert care. Always and most of all, thanks to Sean McElvogue.

SO THERE were kookaburras here. This was the first thing Yolanda knew in the dark morning. (That and wheres my durries?) Two birds breaking out in that loose, sharp cackle, a bird call before the sun was up, loud and lunatic.

She got out of the bed and felt gritty boards beneath her feet. There was the coarse unfamiliar fabric of a nightdress on her skin. Who had put this on her?

She stepped across the dry wooden floorboards and stood, craning her neck to see through the high narrow space of a small window. The two streetlights she had seen in her dream turned out to be two enormous stars in a deep blue sky. The kookaburras dazzled the darkness with their horrible noise.

Later there would be other birds; sometimes she would ask about them, but questions made people suspicious and they wouldnt answer her. She would begin to make up her own names for the birds. The waterfall birds, whose calls fell tumbling. And the squeakers, the tiny darting grey ones. Who would have known there could be so many birds in the middle of absolutely fucking nowhere?

But that would all come later.

Here, on this first morning, before everything began, she stared up at the sky as the blue night lightened, and listened to the kookaburras and thought, Oh, yes, you are right. She had been delivered to an asylum.

She groped her way along the walls to a door. But there was no handle. She felt at its edge with her fingernails: locked. She climbed back into the bed and pulled the sheet and blanket up to her neck. Perhaps they were right. Perhaps she was mad, and all would be well.

She knew she was not mad, but all lunatics thought that.

When they were small she and Darren had once collected mounds of moss from under the tap at the back of the flats, in the dank corner of the yard where it was always cool, even on the hottest days. They prised up the clumps of moss, the earth heavy in their fingers, and it was a satisfying job, lifting a corner and being careful not to crack the lump, getting better as they went at not splitting the moss and pulling it to pieces. They filled a crackled orange plastic bucket with the moss and took it out to the verge on the street to sell. Moss for sale! they screamed at the hot cars going by, giggling and gesturing and clowning, and, Wouldja like ta buy some moss? more politely if a man or woman walked past. Nobody bought any moss, even when they spread it beautifully along the verge, and Darren sent Yolanda back twice for water to pour over it, to keep it springy to the touch. Then they got too hot, and Darren left her there sitting on the verge while he went and fetched two cups of water, but still nobody bought any moss. So they climbed the stairs and went inside to watch TV, and the moss dried out and turned grey and dusty and died.

This was what the nightdress made her think of, the dead moss, and she loved Darren even though she knew it was him who let them bring her here, wherever she was. Perhaps he had put her in the crazed orange bucket and brought her here himself.

What she really needed was a ciggy.

While she waited there in the bed, in the dead-moss nightdress and the wide silencethe kookaburras stopped as instantly as they beganshe took an inventory of herself.

Yolanda Kovacs, nineteen years eight months. Good body (she was just being honest, why would she boast, when it had got her into such trouble?). She pulled the rustling nightdress closerit scratched less, she was discovering, when tightly wrapped.

One mother, one brother, living. One father, unknown, dead or alive. One boyfriend, Robbie, who no longer believed her (at poor Robbie, the rush of a sob in her throat. She swallowed it down). One night, one dark room, that bastard and his mates, one terrible mistake. And then one giant fucking unholy mess.

Yolanda Kovacs, lunatic. And that word frightened her, and she turned her face and cried into the hard pillow.

She stopped crying and went on with her inventory. Things missing: handbag, obviously. Ciggies (almost full pack), purple lighter, phone, make-up, blue top, bra, underpants, skinny jeans. Shoes. Three silver rings from Bali, reindeer necklace from Darren (she patted her chest for it again, still gone).

Yolanda looked up at the dark window. Oh, stars. Stay with me. But very soon the sky was light and the two stars had gone, completely.

She breathed in and out, longed for nicotine, curled in the bed, watching the door.

IN A patch of sunlight Verla sits on a wooden folding chair and waits. When the door opens she holds her breath. It is another girl who comes into the room. They lock eyes for an instant, then look away to the floor, the walls.

The girl moves stiffly in her weird costume, taking only a few steps into the room. The door has closed behind her. The only spare chair is beside Verlas, so Verla gets up and moves to the window. It is too much, that she be put so close to a stranger. She stands at the window, looking out through a fly-spotted pane at nothing. There is bright sunlight coming into the room, but only reflected off the white weatherboards of another building just metres away. She presses her face to the glass but can see no windows anywhere along the length of that building.

She can feel the other girl behind her in the room, staring at her peculiar clothes. The stiff long green canvas smock, the coarse calico blouse beneath, the hard brown leather boots and long woollen socks. The ancient underwear. It is summer. Verla sweats inside them. She can feel it dawning on the other girl that she is a mirror: that she too wears this absurd costume, looks as strange as Verla does.

Verla tries to work out what it was she had been given, scanning back through the vocabulary of her fathers sedatives. Midazolam, Largactil? She wants to live. She tries wading through memory, logic, but cant grasp anything but the fact that all her own clothesand, she supposes, the other girlsare gone. She blinks a slow glance at the girl. Tall, heavy-lidded eyes, thick brows, long black hair to her waist is all Verla sees before looking away again. But she knows the girl stands there dumbly with her hands by her sides, staring down at the floorboards. Drugged too, Verla can tell from her slowness, her vacancythis runaway, schoolgirl, drug addict? Nun, for all Verla knows. But somehow, even in this sweeping glance, the girl seems familiar.

She understands fear should be thrumming through her now. But logic is impossible, all thinking still glazed with whatever they have given her. Like the burred head on a screw, her thoughts can find no purchase.

Verla follows the girls gaze. The floorboards glisten like honey in the sun. She has an impulse to lick them. She understands that fear is the only thing now that could conceivably save her from what is to come. But she is cotton-headed, too slow for that. The drug has dissolved adrenaline so completely it almost seems unsurprising to be here, with a stranger, in a strange room, wearing this bizarre olden-day costume. She can do nothing to resist it, cannot understand nor question. It is a kind of dumb relief.

Next page