ALSO BY BRIAN HAYES

Infrastructure: A Field Guide

to the Industrial Landscape

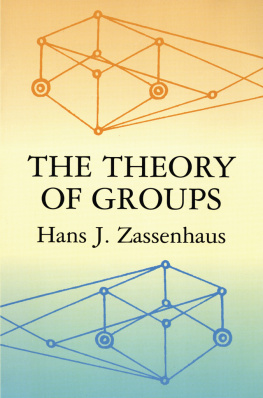

Group Theory in the Bedroom,

and

Other Mathematical Diversions

Group Theory in the Bedroom,

and

Other Mathematical Diversions

BRIAN HAYES

Hill and Wang

A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright 2008 by Brian Hayes

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2008

The essay Clock of Ages was originally published

in The Sciences, the magazine of the New York

Academy of Sciences. All other essays originally

appeared in American Scientist, the magazine

of Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hayes, Brian.

Group theory in the bedroom, and other mathematical diversions / Brian Hayes.1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8090-5219-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8090-5219-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Technology 2. Science. I. Title.

T185.H39 2008

500dc22

2007023337

Designed by Brian Hayes

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For all my editors

Contents

Preface

You walk onto the stage with a violin in your hand, and the audience goes quiet as the conductor nods in your direction. Then you realize you have not rehearsed the Paganini. As a matter of fact, youve never played the violin in your life.

Variations on this classic dream have haunted my nights for years, and once I lived through a waking version of it. In the early 1980s Scientific American magazine, where I was working as an editor, wanted to launch a new monthly column called Computer Recreations, a department concerned with the pleasures of computation. I volunteered to write it. The first thing I had to do was go out and buy a computer, because I had never laid hands on one.

The weeks that followed brought moments of sweaty-palmed tension and doubt, but the eventual outcome was not the nightmare I had feared. One reason is that I got a lot of help, including patient tutoring from some legendary wizards of the computing community, as well as advice from Martin Gardner and Douglas Hofstadter, whose columns had occupied the same place in the magazine in years gone by. Moreover, I discovered that the computer is not like the violin: it doesnt take inborn genius or a lifetime of practice to get sweet music out of it. On the contrary, the computer is a peculiarly forgiving instrument that not only amplifies our talents but also compensates for our flaws and failings. At a trivial level, we see this every day when a word processor corrects our spelling, or when Google fills a lapse in memory. In deeper ways, too, the computer serves as an aid to understanding, exploration, and problem solving.

My gig as the Computer Recreations columnist at Scientific American lasted only a few months; I had to return to my editorial duties. But that brief flirtation with writing about computing and mathematics made a lasting impression; when I left the staff of the magazine a year later, I was determined to rekindle the romance. I wrote a number of pieces for a magazine called Computer Language and then several more for The Sciences, the magazine of the New York Academy of Sciences. Sadly, both of those publications are now deceased. Since 1993 I have been writing a column called Computing Science for American Scientist, the magazine of Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society. Clock of Ages, the first chapter in this collection, appeared in The Sciences; all the rest of the essays were first published in American Scientist.

The topics included here range from deadly serious (war and peace, wealth and poverty) to utterly frivolous (the mathematics of mattress flipping). Two of the pieces look back to earlier eras when computers were built out of brass gears instead of silicon chips. One essay describes imaginary genetic codes that seem far more elegant (to my taste, anyway) than natures own scheme for interpreting DNA. Yet another chapter takes up the surprisingly tricky question of what it means for two things to be equal. The slogan under which I beganthe pleasures of computationstill seems an apt description of what its all about.

The essays cover a time span of a decadeand some of them show their age. At the end of each chapter I have appended a section of afterthoughts to bring the discussion up to date. Within the text of the essays I have tried to restrain myself from making extensive changes, but the truth is, I am a notorious itchy pencil; I cant keep my hands off a manuscript. Various minor errors have been silently corrected, and in several places I couldnt resist the temptation to improve a paragraph or clarify a passage. Major goofsand there are a few of themare explained in the afterthoughts.

Each of these essays should be seen as a collaboration between the author and an editor. I particularly want to acknowledge the contributions of Peter Brown at The Sciences (he is now at Scientific American) and Rosalind Reid, David Schneider, and Fenella Saunders at American Scientist. (I also thank those magazines for their cooperation in allowing the reprinting of this material.) Joseph Wisnovsky, a friend and colleague of thirty years, presided over the publication of this book. Finally, all of my work owes a debt to the late Dennis Flanagan, editor of Scientific American through all its best years and mentor to a generation of science writers.

Group Theory in the Bedroom,

and

Other Mathematical Diversions

CHAPTER 1

Clock of Ages

December 1999. As the world spirals on toward 01-01-00, survivalists are hoarding cash, canned goods, and shotgun shells. Its not the Rapture or the Revolution they await, but a technological apocalypse. Y2K! The lights are going out, they warn. Banks will fail. Airplanes may crash. Your VCR will go on the blink. Who could have foreseen such turmoil? Decades back, one might have predicted anxiety and unrest at the end of the millennium, but no one could have guessed that the cause would be an obscure shortcut written into computer software by unknown programmers of the 1960s and 70s. To save a few bytes of computer memory, they left room for only the final two digits of the year.

We now know that civilization did not collapse on January 1, 2000. Y2K was a nonevent. Nevertheless, in hindsight those programmers do seem to have been pretty short on foresight. How could they have failed to look beyond year 99? But I give them the benefit of the doubt. All the evidence suggests they were neither stupid nor malicious. What led to the Y2K bug was not arrogant indifference to the future. (Ill be retired by then. Let the next shift fix it.) On the contrary, it was an excess of modesty. (Theres no way my code will still be running thirty years from now.) The programmers could not envision that their hurried hacks and kludges would become the next generations legacy systems.

Against this background of throwaway products that somebody forgot to throw away, it may be instructive to reflect on a computational device built in a much different spirit. This is a machine carefully crafted for Y2K compliance, even though it was manufactured at a time when the millennium was still a couple of lifetimes away. As a matter of fact, the computer is equipped to run through the year 9999, and perhaps even beyond with a simple Y10K patch. This achievement might serve as an object lesson to the software engineers of the present era. But I am not quite sure just what the lesson is.

Next page