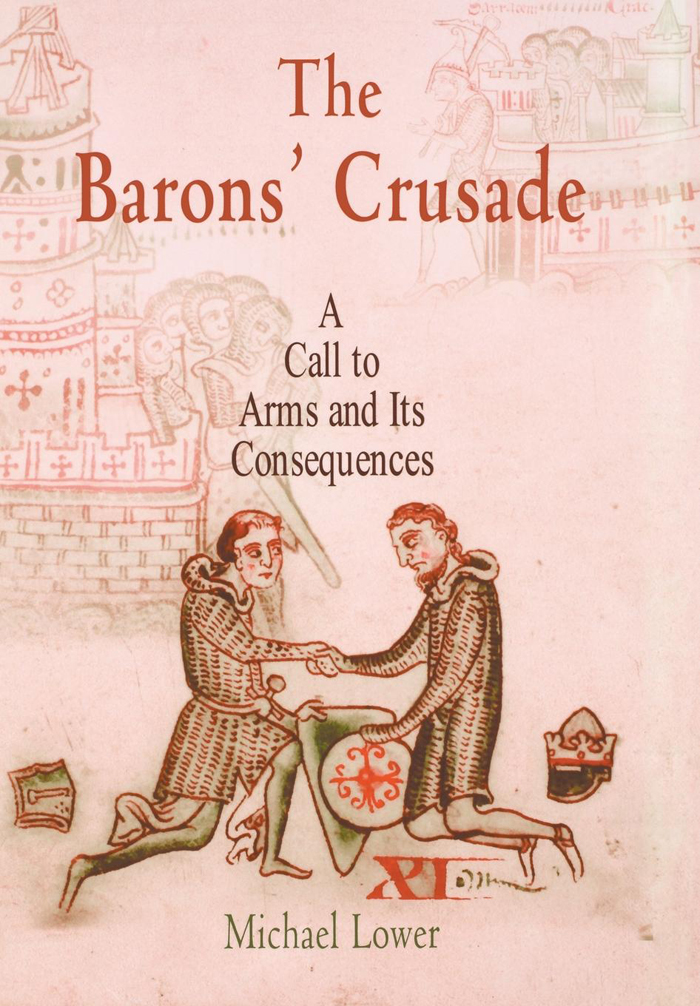

Lower - The Barons Crusade

Here you can read online Lower - The Barons Crusade full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Barons Crusade: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Barons Crusade" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lower: author's other books

Who wrote The Barons Crusade? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Barons Crusade — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Barons Crusade" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Barons Crusade

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

A Call to Arms and Its Consequences

Michael Lower

Map 1. Western Europe at the time of the Barons Crusade.

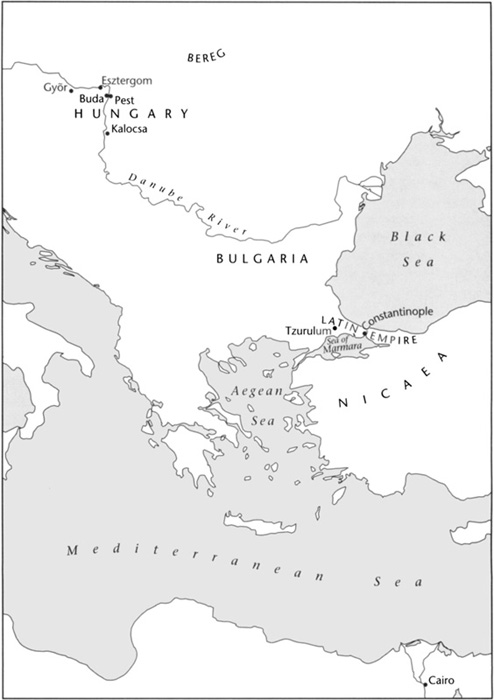

Map 2. The Latin empire and its neighbors at the time of the Barons Crusade.

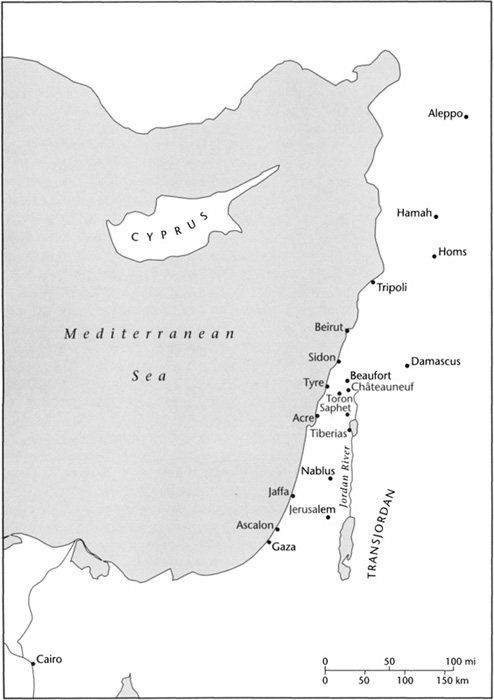

Map 3. The Holy Land at the time of the Barons Crusade.

Copyright 2005 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lower, Michael.

The Barons Crusade : a call to arms and its consequences / Michael Lower.

p. cm. (Middle ages series)

ISBN 0-8122-3873-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

1. Crusade, 12391241. I. Title. II. Series

D166.5 .L69 2005

909.07dc22

2004066145

For Peter and Triene Lower

The Preaching of the Holy Land Crusade: The Plan

During the fall of 1234 Pope Gregory IX turned his full attention to launching an expedition in aid of the Holy Land, devising a preaching campaign that was ambitious in scope and novel in conception. The campaign was an unprecedented attempt to transform crusading into a universal Christian activity. It tried for the first time to make taking the cross a general practice appropriate and desirable for all members of Christendom. What most distinguished the campaign was its appeal to a mass audience. Gregorys preachers exhorted everyone to swear a crusade vow: women as well as men, the old as well as the young, the sick as well as the healthy, the poor as well as the rich. The idea was not to send the populus Christianus on the march. Gregory had no intention of allowing everyone who took the cross to serve in the crusade army. Instead those deemed unsuitable to participate in a military campaign would be made to redeem, or buy back, their vows for a cash payment, in return for the full indulgence of sins granted to those who went on the crusade in person. The money raised from these redemptions would help fund a force of expert fighters. What Gregory had in mind was a mass mobilization of Christian purses, not arms.

In the twelfth century, popes had taken a more straightforward approach to crusade recruitment. They encouraged men of military inclination to go on crusade and encouraged everyone else to remain at home. Preaching campaigns of the era focused primarily on recruiting crusaders, not generating funding for crusades.

But this approach to promoting crusades was not as successful as the popes would have liked. Papal admonitions did not prevent inexperienced fighters from setting out for the East. Large numbers of them took part in the Second and Third Crusades. When these expeditions failed, noncombatants received more than their fair share of the blame. As it turned out, the Fourth Crusade suffered the gravest financial crisis yet. Having reached the bottom of its coffers before it set sail from Venice, the expedition never managed to make it to the Holy Land, let alone provide it with effective aid.

In the wake of more than half a century of unsuccessful crusades to the Holy Land, with none having failed quite as dramatically as the one he himself had launched, Innocent made a change in the way crusades were recruited. He announced the new measure in Quia maior, his crusade bull of 1213 for the Fifth Crusade:

Since it happens that aid to the Holy Land is much impeded or delayed if each must be examined prior to taking the cross as to his fitness and ability to fulfill the vow in person, we allow that anyone who wishes, except persons bound by religious profession, may take the cross, on the assumption that when dire necessity and or plain usefulness may so require, the vow may be commuted, redeemed, or postponed by apostolic command.

With one stroke, the new policy provided a mechanism to both limit noncombatant participation and raise funds. Anyone who wished to swear a crusade vow might do so, regardless of aptitude for warfare; but the pope had exclusive authority to determine how best that votive obligation might be fulfilled: it could be executed as promised, delayed, commuted, or redeemed as he saw fit. It was the last of these powers over the vow that offered the greatest potential as an instrument of recruitment and fundraising. By redeeming vows en masse, Innocent could prevent incapable crusaders from swelling the ranks of the crusade army. At the same time, he could use the money they paid to buy back their vows to subsidize the practiced fighters he wanted for his expedition.

Despite the financial advantage of doing so, Innocent never exploited vow redemption to its full potential. It was, in fact, just one of many new methods he devised to channel enthusiasm for crusading into aid for the Holy Land. Quia maior and Ad liberandam, the decree for the crusade he issued at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, seem to offer every segment of Latin Christian society an appropriate way to contribute to the crusade.

Certainly vow redemption had a place among these new techniques for supporting the crusade; but it was not a predominant one. Innocent may have called upon all Christians to contribute to the crusade in one fashion or another;

Gregory, however, did not follow Honoriuss approach. In his time as a cardinal, Pope Gregory IX, then Ugolino of Ostia, had worked as a legate in Lombardy promoting the Fifth Crusade. and the promotional campaign that Rachel suum videns launched represents the first papal attempt to exploit Innocents vow redemption policy fully.

Historians have generally acknowledged that there was a shift in emphasis toward vow redemption in the thirteenth century, but they have tended to disagree about precisely where, when, and how it took place. Some have dated it to the pontificate of Innocent III, A closer examination of Gregorys campaign will help to delineate more precisely the chronological development of this practice as a papal fundraising and recruitment technique.

More immediately, Gregorys drive for redemption fees influenced the structure of his preaching campaign. It made it desirable for as many people as possible to take the cross. The sum demanded of crusaders to redeem their vows was typically set at the amount they would have spent if they had actually gone overseas.leisure and resources necessary to master mounted combat. In Gregorys day the correlation between reputed military prowess and high economic status was still strong; the merchant elites of the cities were just beginning to break it down. His decision to rely upon vow redemption, therefore, meant that he would need to solicit many small vow redemption fees, rather than a few large ones. The result was a preaching campaign that, in order to achieve success, needed to persuade as many people as possible to swear crusade vows.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Barons Crusade»

Look at similar books to The Barons Crusade. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Barons Crusade and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.