Eight Lectures on Experimental Music

Eight Lectures on Experimental Music

Edited by Alvin Lucier

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown, Connecticut

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2018 Wesleyan University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed and typeset in Calluna by Eric M. Brooks

Christian Wolffs lecture is to be published in his forthcoming book, Occasional Pieces (Oxford University Press, 2017). The lecture has been reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press. It was also published in Christian Wolff, Cues: Writings & Conversations (Cologne: MusikTexte, 1998).

Parts of Steve Reichs lecture were printed in his book Writings on Music, 19652000 (Oxford University Press, 2002). Reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press.

Part of Steve Reichs lecture originally appeared in the Kurt Weill Newsletter (Fall 1992): 10 (2).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

NAMES: Lucier, Alvin editor.

TITLE: Eight lectures on experimental music / edited by Alvin Lucier.

DESCRIPTION: Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, [2017] |

IDENTIFIERS: LCCN 2017019112 (print) | LCCN 2017021187 (ebook) | ISBN 9780819577641 (ebook) | ISBN 9780819577634 (cloth: alk. paper)

SUBJECTS: LCSH: Music20th centuryHistory and criticism.

CLASSIFICATION: LCC ML197 (ebook) | LCC ML197 .E33 2017 (print) | DDC 780.9/04dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019112

5 4 3 2 1

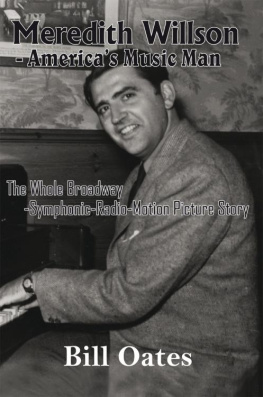

Cover illustration: String Noise duo at the Paula Cooper Gallery, in front of Sol LeWitt wall drawing, by Mimi Johnson. Sol LeWitt wall drawing courtesy of Artists Rights Society.

To

RICHARD K. WINSLOW,

who, with the calm of a deep sea diver,

changed the teaching of music at

Wesleyan and in the world

Contents

INTRODUCTION

ix

1 JAMES TENNEY

1

2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF

12

3 ROBERT ASHLEY

31

4 MARYANNE AMACHER

45

5 LA MONTE YOUNG

59

6 STEVE REICH

80

7 MEREDITH MONK

104

8 PHILIP GLASS

120

Introduction

One of the benefits of being the John Spencer Camp Professor of Music at Wesleyan is that each year you have a discretionary fund that you may use to enrich programs of your choice within the Music Department. Between 1989 and 2002, I invited eight composers whose music I featured in my lecture course, Music 109, Introduction to Experimental Music, to come to campus to talk about their work. The lectures were presented in the World Music Hall in the Center for the Arts at Wesleyan. Each was recorded and transcribed by a Music Department graduate student, then lightly edited by me. I made sure to keep the flavor of each composers speaking style while making necessary corrections in grammar and punctuation in order to give the reader the clearest version of the composers ideas. Each lecture was then sent to the composer for acceptance, verification, corrections, and additions. They appear in this book in the order in which they were given. Whenever possible, a lecture included a live performance of the lecturers work, sometimes as a surprise gift.

In my many years of teaching, I have never felt inclined to be inclusive or to survey the entire field of experimental music; rather, I have concentrated on those composers whose music I have loved and admired and who I have felt have broken new ground in defining what music is now or may be in the future. The work of the composers included in this book falls into two broad categories: first, that which more directly follows the spirit and tradition of American experimentalism, from Ives to Cage, and, second, that which takes inspiration from the music of non-Western cultures, particularly West Africa, Indonesia, and India. Often these two categories overlap.

As the eight composers talked about their work, it became clear that the subjects they talked about, while related to their own music, included an astonishing variety of ideas: the exploration of acoustic phenomena, music of very long duration, talking as music, repetition, pulse, the threshold of audibility, return to tonality, opera for television, the placement and propagation of sound in architectural spaces, song, heterophony, politics, music for the theater, musics place in society and its relationship to popular and world music, the reuse of traditional compositional techniques.

I realize that the term experimental is problematic. Many composers hate the term. Edgard Varse said: I do not write experimental music. My experimenting is done before I make the music. Afterwards, it is the listener who must experiment. John Cage, however, describes it as music in which the outcome is uncertain. Works using chance operations or open forms or that set in motion procedures that are neutral in intent may be good examples of the experimental. Some works even resemble experiments in the scientific sense, in that something is discovered during the course of the performance rather than that a preconceived idea or form is brought into being by the will or skill of the composer.

The terms new or contemporary are too general and may refer to any music of the present. And while it may be radical and even experimental in some way, avant-garde refers to a music that merely updates that which precedes it. So, for want of a better word, let us simply accept the term experimental.

John Spencer Camp graduated from Wesleyan in 1878, received a masters degree in 1881, and spent most of his life as a church organist in Hartford, Connecticut. One would think that church organists are conservative by nature, until one remembers that they in fact have to invent and mix their own sounds by choosing from a wide variety of stops, often on extremely large and complex instruments. They are composers, in a way, or at least orchestrators of every piece they play. For that reason, I like to think that while Mr. Camp may not have understood this music entirely, he would have had to admire the skills of the composers in creating their own sounds and putting them together in their works. In 1921, he became CEO of the Austin Organ Company. John Spencer Camp died in 1946.

A person is fortunate to have one good idea in his or her lifetime. Richard K. Winslow, longtime chair of the Wesleyan Music Department and second John Spencer Camp Professor of Music had, in fact, two good ideas. First, along with ethnomusicologist David McAllester, he founded the World Music Department at Wesleyan, an act that changed the teaching of music throughout the world. Wesleyan was the first university music department in which world music was an integral part of the curriculum. Second, very early on, Winslow recognized the genius of John Cage. In 1960, he invited Cage to spend a year at Wesleyans Center for Advanced Studies and was responsible for the publication of Cages germinal book, Silence, by Wesleyan University Press. Experimental music at Wesleyan (and these lectures) would not have come into existence without Richard Winslows vision.

Next page