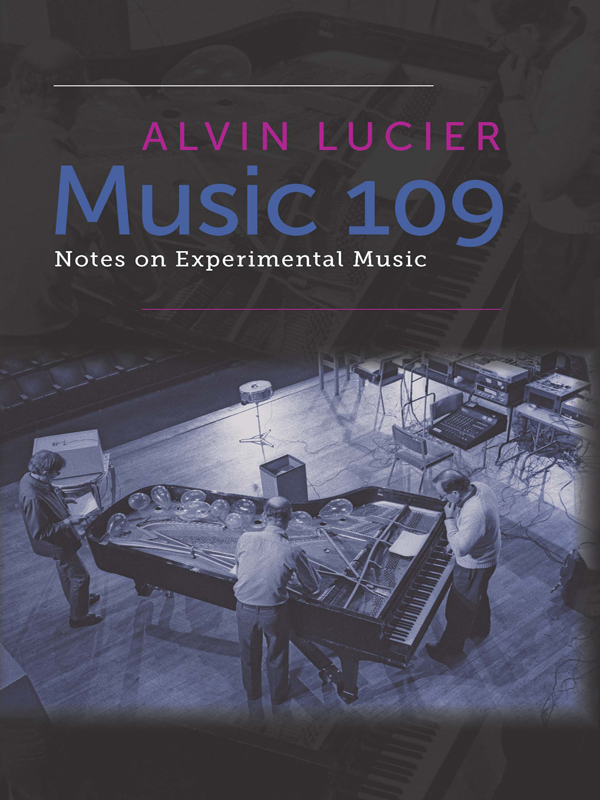

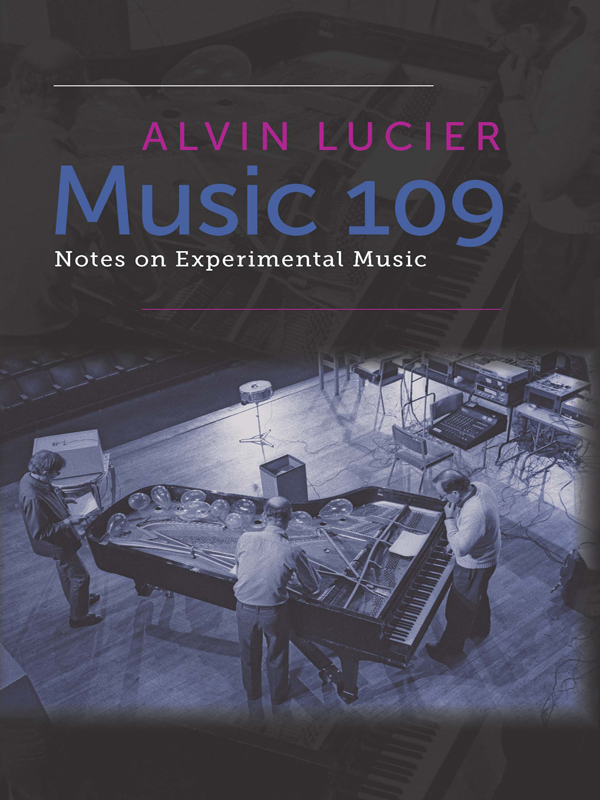

MUSIC 109

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2012 Alvin Lucier

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Eric M. Brooks

Typeset in Whitman and Calluna Sans

by Passumpsic Publishing

Wesleyan University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper.

Sample of Drumming score by Steve Reich, copyright 1973 by Hendon Music, Inc.

Reprinted by permission.

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lucier, Alvin.

Music 109: notes on experimental music / Alvin Lucier; foreword by Robert Ashley.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-8195-7297-4 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8195-7298-1 (ebook)

1. Lucier, Alvin. 2. Avant-garde (Music)

I. Title.

ML410.L8973A3 2012

780.92dc23 2012008721

5 4 3 2 1

Again for

WENDY & AMANDA

And for

SUSAN & SUE-ELLEN

FOREWORD

Music 109 is a thorough, modern history of a particular group of composers and their work. This history begins in the 1950s and ends roughly in the 1980s. In colleges and universities where the history of contemporary music is part of the curriculum, this book will solve many teachers problems about what ideas, what composers, and what compositions are important to understand from that history. What Alvin Lucier presents so clearly here, with quotations from scores, will make a classroom discussion of those ideas easy.

We are in the time of what young composers now speak of as the music that has influenced their ideas. The study begins after the time of Harry Partch, Conlin Nancarrow, Henry Cowell, and Virgil Thompson. But even with its attention solely to the music of the past fifty years, it takes us to composers and compositions that for many younger musicians are almost legendarycompositions that everybody has heard, or heard about, but that in most cases have not been studied.

As we read, we discover that many of these compositions and the ideas under discussion have not previously been understood as coming from a common purpose or shared idea. In this way, the book is a serious academic history, but Lucier relates these ideas to us in the form of stories, talking to us as he talked to his students. He is never ironic about what he is doing. His enthusiasm is clear and warm hearted; this music means something to him.

Many of the compositions discussed here, and the ideas they represent, remind me of times I have spent with Alvin. I read the title Chambers and I am in Scandinavia, probably at the Sonja Henie museum in Oslo. There are eight of us on this tour. When it comes time to play Chambers everybody takes some sort of chamber out of the suitcase that Alvin has broughtsmall, covered pots and jars, tea kettles, tin cans, and, finally, four or five conch shells (in the days before conch shells were available from the instrument-rental shop). Everybody walks around the performance space presenting sounds to the audience. Then everybodyone by one and very slowlywalks through the doors of the concert hall into a garden that adjoins the hall and disappears into the darkness outside. The concert has ended in a kind of magic.

Then I am in a New Englandstyle house across the street from the Wesleyan campus. Alvin is attached to a mysterious device through wires patched to his head. I dont know what he is going to do. He closes his eyes and appears to be concentrating fiercely on something. A few seconds later there are sounds coming from one of the other rooms in the house. They are percussion sounds. But even now, decades later, I remember vividly that I thought the sounds were of distant thunder. I had never heard that sound in music. I was enchanted.

Then, at the Rose Art Museum. Alvin has invited David Behrman, Gordon Mumma, and me to give a concert there. (Maybe this was the occasion when, after the concert, we were having a drink at Alvins house, and it occurred to Alvin and me to invent the Sound Arts Union. We went into the other room to check the idea with David and Gordon. They approved.) For the concert Alvin performs Wolfman, a recent composition of mine. In just a few years I came to realize that Alvin was the only person ever to perform the piece correctly.

Finally, for this account, one story of the numberless times we spent together: Alvin comes to Ann Arbor as a guest of the ONCE Festival. Four performers are preparing to use his Sondols (devices that give off powerful clicking sounds that bounce off the various physical objects in the space and, when the performer gives attention to the clicks, help the performer negotiate the space). The lights go down. The performance starts. The gallery is filled with loud clicks bouncing off everything. This is an amazing sound. Nobody in the audience has had this experience of sound.

Alvin is characteristically modest in Music 109 about his major contribution to this half-century of music in which the language changed so radically. In fact, he is modest about the change itselfas if this sort of thing happens all the time. This book makes the work of a couple of dozen composersthe pioneers in the world of sound-as-more-important-(for the moment)-than-what-the-composer-does-with-the-soundsimple, finally, to understand. And these are the composers and the compositions important to listen toin order to understand.

Robert Ashley

MUSIC 109

SYMPHONY

Symphony No. 4

When I went to college we studied the masterpieces of European music. If you wanted to be a professional composer, you would go to Europe after college to finish up your musical education. Before World War I many American composers went to Munich to study with an organist named Josef Rheinberger; after the war they went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger. Walter Piston and Aaron Copland studied with her. My three composition teachers in graduate school studied with her. The entire batch of American students was nicknamed the Boulangerie. Thats French for bakery. Anyway, one felt that ones spiritual home was in Europe. We all thought that American classical music wasnt as good as European music. And for good reasons. Its hard to compete with Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, not to mention such modern masters as Bartok, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky. We all had inferiority complexes. There was no concept of World Music then. And even though we all loved jazz, there were no courses devoted to it. We simply played it outside of school. Its very different now, but when I was in college that was true.

Charles Ives graduated from Yale in 1898. He studied composition with Horatio Parker, who, by the way, had studied with Rheinberger. When Ives left Yale he knew he couldnt make a living as a composer, so he went into the insurance business. The firm of Ives and Myrick became one of the most successful insurance companies in New York. He wrote music at night, knowing that much of his work would never be played, at least in his lifetime. When Ives retired because of ill health, he was a wealthy man, but he only took enough money out of his company to live in reasonable comfort.

Throughout his creative life, Ives wrote startlingly original works using polychords, polyrhythms, quartertones, and other innovative devices he learned from his father, a band conductor and indefatigable music experimenter. His Symphony No. 4 (written between 1910 and 1916 but not performed until 1965, by Leopold Stokowski) requires three conductors to manage separate instrumental groups playing in different meters and tempos. In the first movement, a distant chamber orchestra, consisting of harp and solo strings, usually situated in the balcony, plays heavenly music against the heavy, symphonic music of the main orchestra. (As a child Ives had watched a parade in Danbury during which two bands marched from opposite ends of the street, playing in different keys and tempos.) This movement is only about three minutes long. Its marked

Next page