CONTENTS

CONTENTS

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

List of Maps

Preface

INTRODUCTION / Holmbergs Mistake

1. A View from Above

PART ONE / Numbers from Nowhere?

2. Why Billington Survived

3. In the Land of Four Quarters

4. Frequently Asked Questions

PART TWO / Very Old Bones

5. Pleistocene Wars

6. Cotton (or Anchovies) and Maize (Tales of Two Civilizations, Part I)

7. Writing, Wheels, and Bucket Brigades (Tales of Two Civilizations, Part II

PART THREE / Landscape with Figures

8. Made in America

9. Amazonia

10. The Artificial Wilderness

CODA

11. The Great Law of Peace

Afterword to the Vintage Edition

Appendixes

A. Loaded Words

B. Talking Knots

C. The Syphilis Exception

D. Calendar Math

Notes

Bibliography

Map Credits

Illustration Credits

Acknowledgments

Charles C. Mann 1491

Also by Charles C. Mann

Acclaim for Charles C. Manns 1491

Copyright

For the woman in the next-door office

Cloudlessly, like everything else

CCM

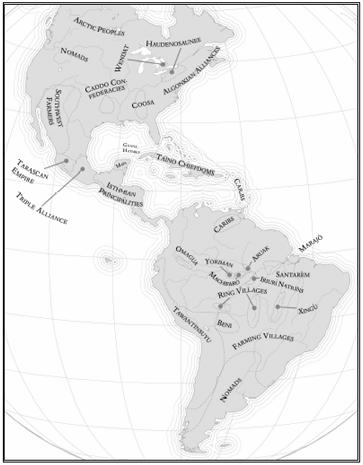

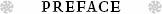

NATIVE AMERICA, 1491 A.D.

The seeds of this book date back, at least in part, to 1983, when I wrote an article for Science about a NASA program that was monitoring atmospheric ozone levels. In the course of learning about the program, I flew with a research team in a NASA plane equipped to sample and analyze the atmosphere at thirty thousand feet. At one point the group landed in Mrida, in Mexicos Yucatn Peninsula. For some reason the scientists had the next day off, and we all took a decrepit Volkswagen van to the Maya ruins of Chichn Itz. I knew nothing about Mesoamerican cultureI may not even have been familiar with the term Mesoamerica, which encompasses the area from central Mexico to Panama, including all of Guatemala and Belize, and parts of El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua, the homeland of the Maya, the Olmec, and a host of other indigenous groups. Moments after we clambered out of the van I was utterly enthralled.

On my ownsometimes for vacation, sometimes on assignmentI returned to Yucatn five or six times, three times with my friend Peter Menzel, a photojournalist. For a German magazine, Peter and I made a twelve-hour drive down a terrible dirt road (thigh-deep potholes, blockades of fallen timber) to the then-unexcavated Maya metropolis of Calakmul. Accompanying us was Juan de la Cruz Briceo, Maya himself, caretaker of another, smaller ruin. Juan had spent twenty years as a chiclero, trekking the forest for weeks on end in search of chicle trees, which have a gooey sap that Indians have dried and chewed for millennia and that in the late nineteenth century became the base of the chewing-gum industry. Around a night fire he told us about the ancient, vine-shrouded cities he had stumbled across in his rambles, and his amazement when scientists informed him that his ancestors had built them. That night we slept in hammocks amid tall, headstone-like carvings that had not been read for more than a thousand years.

My interest in the peoples who walked the Americas before Columbus only snapped into anything resembling focus in the fall of 1992. By chance one Sunday afternoon I came across a display in a college library of the special Columbian quincentenary issue of the Annals of the Association of American Geographers. Curious, I picked up the journal, sank into an armchair, and began to read an article by William Denevan, a geographer at the University of Wisconsin. The article opened with the question, What was the New World like at the time of Columbus? Yes, I thought, what was it like? Who lived here and what could have passed through their minds when European sails first appeared on the horizon? I finished Denevans article and went on to others and didnt stop reading until the librarian flicked the lights to signify closing time.

I didnt know it then, but Denevan and a host of fellow researchers had spent their careers trying to answer these questions. The picture they have emerged with is quite different from what most Americans and Europeans think, and still little known outside specialist circles.

A year or two after I read Denevans article, I attended a panel discussion at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Called something like New Perspectives on the Amazon, the session featured William Bale of Tulane University. Bales talk was about anthropogenic forestsforests created by Indians centuries or millennia in the pasta concept Id never heard of before. He also mentioned something that Denevan had discussed: many researchers now believe their predecessors underestimated the number of people in the Americas when Columbus arrived. Indians were more numerous than previously thought, Bale saidmuch more numerous. Gee, someone ought to put all this stuff together, I thought. It would make a fascinating book.

I kept waiting for that book to appear. The wait grew more frustrating when my son entered school and was taught the same things I had been taught, beliefs I knew had long been sharply questioned. Since nobody else appeared to be writing the book, I finally decided to try it myself. Besides, I was curious to learn more. The book you are holding is the result.

Some things this book is not. It is not a systematic, chronological account of the Western Hemispheres cultural and social development before 1492. Such a book, its scope vast in space and time, could not be writtenby the time the author approached the end, new findings would have been made and the beginning would be outdated. Among those who assured me of this were the very researchers who have spent much of the last few decades wrestling with the staggering diversity of pre-Columbian societies.

Nor is this book a full intellectual history of the recent changes in perspective among the anthropologists, archaeologists, ecologists, geographers, and historians who study the first Americans. That, too, would be impossible, for the ramifications of the new ideas are still rippling outward in too many directions for any writer to contain them in one single work.

Instead, this book explores what I believe to be the three main foci of the new findings: Indian demography (Part I), Indian origins (PartII), and Indian ecology (Part III). Because so many different societies illustrate these points in such different ways, I could not possibly be comprehensive. Instead, I chose my examples from cultures that are among the best documented, or have drawn the most recent attention, or just seemed the most intriguing.

Throughout this book, as the reader already will have noticed, I use the term Indian to refer to the first inhabitants of the Americas. No question about it, Indian is a confusing and historically inappropriate name. Probably the most accurate descriptor for the original inhabitants of the Americas is Americans. Actually using it, though, would be risking worse confusion. In this book I try to refer to people by the names they call themselves. The overwhelming majority of the indigenous peoples whom I have met in both North and South America describe themselves as Indians. (For more about nomenclature, see Appendix A, Loaded Words.)

CONTENTS

CONTENTS