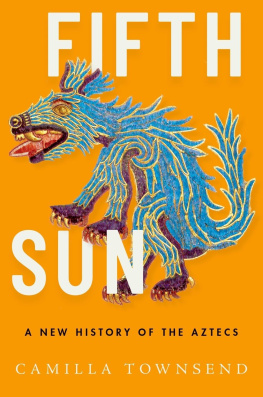

Fifth Sun

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Townsend, Camilla, 1965 author.

Title: Fifth sun : a new history of the Aztecs / Camilla Townsend.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019003623 (print) | LCCN 2019004887 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190673079 (updf) | ISBN 9780190673086 (epub) | ISBN 9780190673062 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: AztecsHistory. | AztecsFirst contact with Europeans. | AztecsHistoriography. | MexicoHistoryConquest, 15191540.

Classification: LCC F1219.73 (ebook) | LCC F1219.73 .T67 2019 (print) | DDC 972dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019003623

Title Page Art: Mexica government officials in full battle gear. The Bodleian Libraries, the University of Oxford, Codex Mendoza, MS. Arch. Selden. A.1, folio 67r.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc. United States of America

Contents

As the Aztecs well knew, no one ever accomplishes anything alone. Certainly I owe my ability to write this book to the hundreds of people whose lives have touched mine along the waythose who raised me and loved me, educated me or studied with me, worked with me as colleagues, or shared their knowledge of early Latin America. The list is so long, and the influences so varied, that I sometimes find the thought overwhelming. Please know, every one of you, that I feel the gratitude I should, and like the Aztecs, hope to pay my debt to the universe through the way I live my life and my efforts on behalf of the people of the future.

There are two groups of people who have helped me so much on this project that I must call out their names individually. One group consists of the Nahuatl scholars whose work made this book possible. I dedicated the last book I published to two recently deceased intellectual giants, James Lockhart and Luis Reyes Garca, whose translations of Nahuatl texts formed the bedrock of much of my own work. In those pages I also referenced my gratitude to the late Inga Clendinnen and Sabine MacCormack. It has occurred to me since that I should not wait for people to pass away to the next world before speaking aloud of my debts. I deeply thank Michel Launey and Rafael Tena, two modest men who have made breath-taking contributions with their work in Nahuatl. You remind me of Nanahuatzin, though I certainly hope you have not felt your work to be a sacrifice.

The other group includes the Mexican intellectualsteachers, professors, researchers, writers, publishers, and filmmakerswho in the past few years have personally welcomed my contributions and offered me their own, thereby enriching this book immeasurably. I humbly thank (in alphabetical order) Sergio Casas Candarabe, Alberto Corts Caldern, Margarita Flores, Ren Garca Castro, Lidia Gmez Garca, Edith Gonzlez Cruz, Mara Teresa Jarqun Ortega, Marco Antonio Landavazo, Manuel Lucero, Hector de Maulen Rodrguez, Erika Pani, Ethelia Ruiz Medrano, Marcelo Uribe, and Ernesto Velzquez Briseo. Your combination of pride in your heritage, openness to others, and intellectual acumen have inspired me more than I can say.

I must not wax poetic and omit to mention matters of daily sustenance; the Aztecs certainly would never have been been so nave. Years ago, the American Philosophical Society awarded a grant that allowed me to travel to the Bibliothque nationale de France and see the work of don Juan Buenaventura Zapata y Mendoza. I got the bug and have pursued the Nahuatl annals ever since. More recently, a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and a sabbatical from Rutgers University allowed me to do the necessary research in the genre as a whole. A Public Scholar award from the National Endowment for the Humanities made it possible for me to take a year off from teaching and write, day in and day out.

The research would not have been possible without the years of painstaking work accomplished by the staffs of the institutions that safeguard the annals and other important texts. A number of them made me welcome over the yearsthe Library and Archive of the Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia in Mexico City, the Bibliothque nationale de France, the British Library, the Library of Uppsala University in Sweden, the New York Public Library, and the Library of the American Museum of Natural History.

I thank my family for being who they are. My sister, Cynthia, and sister-in-law, Patricia, are the bravest of women. Your children and grandchildren will speak of you with love and admiration. My partner, John, and my two sons, Loren and Cian, have made me proud to know them as they have faced lifes challenges. For years now, the three of you have shared me with many othersstudents, aging parents, former foster children, and the historical figures who live in my mindbut it is you who are my precious beloveds, always.

Most of these terms are originally from Nahuatl (N) or Spanish (S).

Acolhua (N). A Nahuatl-speaking ethnic group inhabiting the territory to the east of the great lake in Mexicos central basin in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The group contained several distinct altepetls, including such well-known ones as Texcoco and a town on the site of Teotihuacan.

Altepetl (N). Nahuatl term for any state, no matter how large, but most frequently used to refer to a local ethnic state. A close approximation would be our notion of city-state.

Audiencia (S). The high court of New Spain, residing in Mexico City. In the absence of a sitting viceroy, the governing council of New Spain.

Cabildo (S). Any town council organized in the Spanish style. Used to refer to the local indigenous council governing their communitys internal affairs.

Cacique. An Arawak or Caribbean indigenous word. A ruler, often used as the equivalent of tlatoani. Eventually, the word was used to describe any prominent indigenous person of a noble line.

Calli (N). Literally, a house or household. Often an important metaphor for larger political bodies. Also one of the four rotating names for years.

Calpolli (N). Literally, great house. A key constituent part of an altepetl. We might think of a combined political ward and religious parish.

Chalchihuitl (N). A precious greenstone often translated into English as jade. The Nahuas valued the gem exceedingly, and thus it served as a metaphor for that which was well loved.