THE AZTECS

LOST CIVILIZATIONS

The books in this series explore the rise and fall of the great civilizations and peoples of the ancient world. Each book considers not only their history but their art, culture and lasting legacy and asks why they remain important and relevant in our world today.

Already published:

The Aztecs Frances F. Berdan

The Barbarians Peter Bogucki

Egypt Christina Riggs

The Etruscans Lucy Shipley

The Goths David M. Gwynn

The Greeks Philip Matyszak

The Indus Andrew Robinson

The Persians Geoffrey Parker and Brenda Parker

The Sumerians Paul Collins

THE

AZTECS

LOST CIVILIZATIONS

FRANCES F. BERDAN

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2021

Copyright Frances F. Berdan 2021

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789143614

CONTENTS

CHRONOLOGY

c. AD 1650 | Dominance of Teotihuacan |

c. 9501175 | Dominance of Tula |

11501350 | Migrations of Chichimeca into central Mexico |

1325 | Founding of Tenochtitlan |

142830 | Formation of the Aztec Triple Alliance |

Early 1450s | Devastating famine in central Mexico, especially the Basin of Mexico |

1465 | Chalco conquered, facilitating trade routes to the east and south |

1473 | Tlatelolco conquered by Tenochtitlan |

1479 | Devastating defeat at the hands of the Tarascans |

1487 | Completion of a major expansion of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan |

1502 | Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin succeeds Ahuitzotl as Mexica king |

1504, 1515 | Notable wars between the Triple Alliance and Tlaxcalla and its allies |

1519 | Arrival of Spaniards under Corts near present-day Veracruz |

1519: 8 November | Meeting between Motecuhzoma and Corts at the entrance to Tenochtitlan |

1520: early July | Noche Triste or The Night the Spaniards Died at the Tolteca Canal |

1521: 13 August | Capture of Mexica king Cuauhtemoc by Spaniards |

Volcanic stone sculpture of a man carrying a cacao pod, 14401521.

INTRODUCTION

T he Aztecs were the last of a long succession of great civilizations that developed throughout the many and diverse regions of ancient Mesoamerica. In 1521 they were conquered by Spanish conquistadores and their numerous indigenous allies: at that point the Aztec empire and civilization became, on the surface, lost. Their great capital city was demolished, their state institutions dismantled, their empire dissolved, and their theatrical religious ceremonies superseded by Christian ones. In this sense the Aztecs easily qualify as a fitting subject in this series of Lost Civilizations. But this is only part of the story. The empire may have been lost, but it has not disappeared from view. It is still discoverable.

Written Documents, Archaeology and Ethnography

The Aztecs were literate and amassed enormous libraries. Their pictorial books (codices) were produced by professional scribes and encompassed records as diverse as maps, dynastic and other histories, censuses, financial accounts, calendars, ritual almanacs and cosmological descriptions. Unfortunately, almost all of these books fell victim to the ravages of the conquest and its aftermath. Native books were considered by Spanish ecclesiastics to be books of the Devil and were intentionally and systematically destroyed. However, a few survived and numerous other codices were produced in the early decades after the conquest, executed by native hands at the behest of either indigenous communities or Spanish political and religious overlords. These documents, if carefully filtered for Spanish influences, reveal rich nuggets of information on pre-Spanish Aztec life.

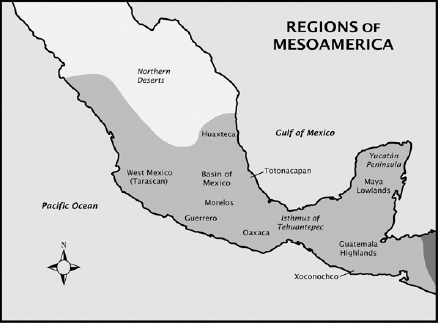

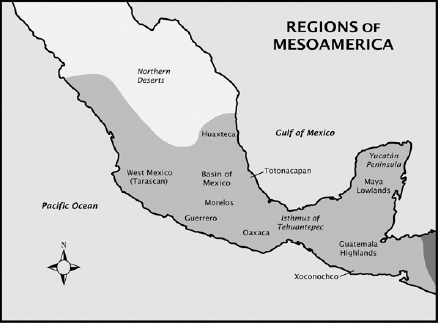

Regions of Mesoamerica during the Late Postclassic era.

Sixteenth-century Spaniards were great fans of the written word and enthusiastically composed a wide variety of fascinating narratives. The conquistadores themselves wrote letters and other accounts describing their early encounters with the native peoples they would later conquer. These include the five letters of Hernando Corts to the king of Spain, a true history written by one of his soldiers, and several shorter but enlightening eyewitness accounts of the conquest itself. In the years following the conquest, Spanish religious persons such as the Dominican friar Diego Durn and the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagn composed lengthy accounts of Aztec history and culture. Much can be believed in these and related accounts: Durn and others mention pictorial codices among their sources, Sahagn worked directly with knowledgeable native men in producing his encyclopaedic Florentine Codex, and native chroniclers such as Fernando Alva de Ixtlilxochitl also relied on pre-Spanish pictorial sources, now lost. And there is more: the Spaniards undertook censuses of native communities under their new colonial rule, produced a wide range of official reports, and inscribed innumerable tax and legal records.

The native people were neither idle nor passive in the face of this avalanche of Spanish documents. Some learned the alphabetic script early on, and produced for themselves and others great quantities of documents including wills, law suits, land claims, complaints and even letters, all in the native Nahuatl language. The language was tenacious: indigenous oral histories augmented by codices were written down in alphabetic script in Nahuatl, so today we have access to chronicles, histories, poetry, songs and sage advice from elders to help us reconstruct details of daily life in the ancient Aztec world.

Despite the richness and abundance of the documentary record, it is invariably flawed. For example, Cortss letters were self-serving and the accounts of other Spanish conquistadores furthered their own personal goals and were grounded in their own cultural preconceptions. Spanish ecclesiastics avidly bent on conversion to Christianity expectedly denigrated native religious beliefs and ceremonies. In another vein, point of view often muddied the written word: for instance, a native noble recounting a pre-Spanish history wrote not only from the perspective of his elevated status but from that of his own particular city. Perspectives may be tied to factors such as social status, residence, ethnicity or occupational group, so intentional or unconscious biases seeped into the written record. Still, we rely heavily on early colonial written sources to look backward and reconstruct pre-Spanish Aztec life; the exercise requires teasing out pre-Columbian realities from colonial influences and transformations. And while documentary sources can be truly enlightening, they do not provide a complete picture of this lost civilization. Many areas of life, such as womens activities and the daily lives of slaves, appear only as fleeting glimpses.

THE AZTECS

THE AZTECS

CONTENTS

CONTENTS