For Michael D. Coe

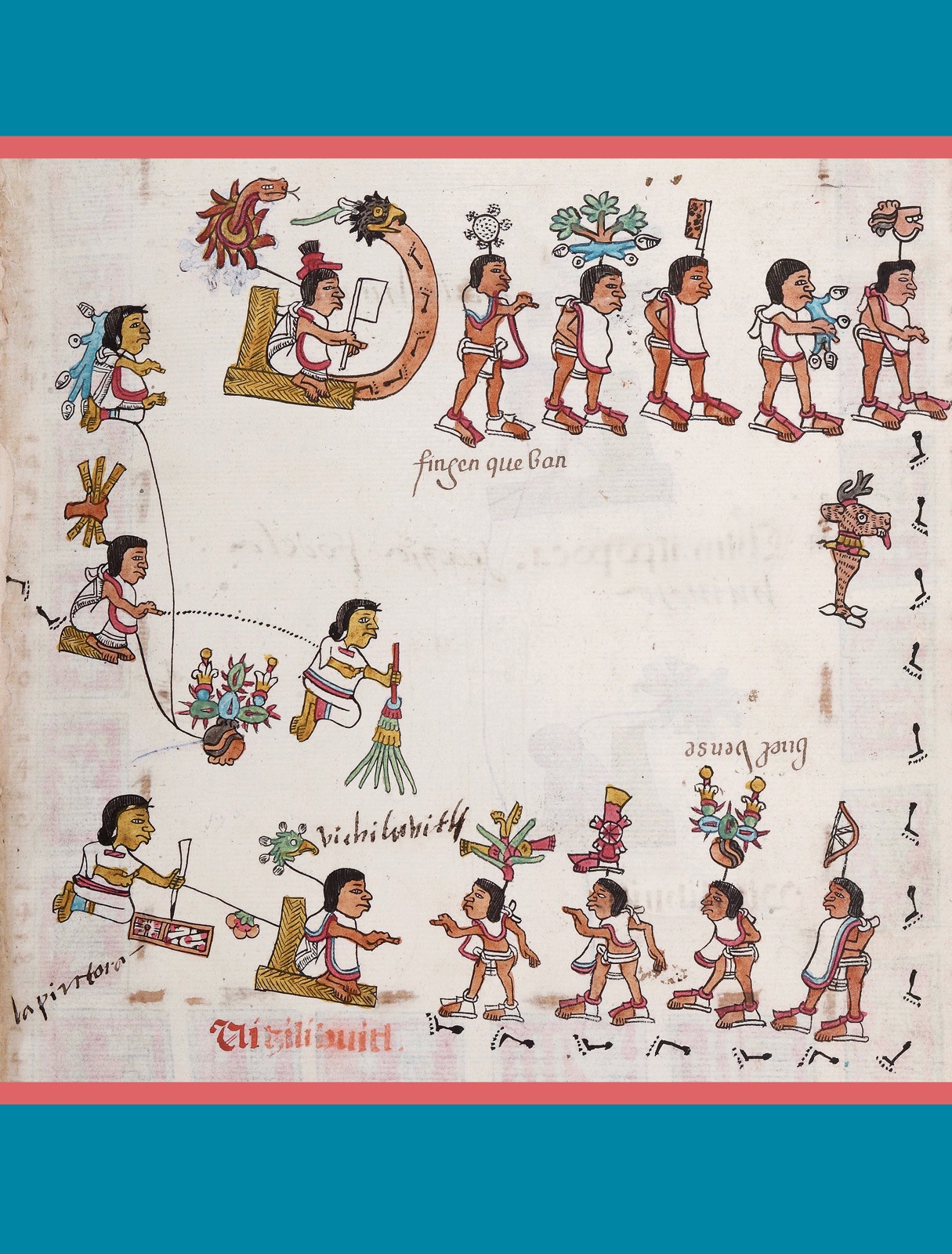

(Cf. Codex Florentinus, Bk. 1, Addendum II)

About the Author:

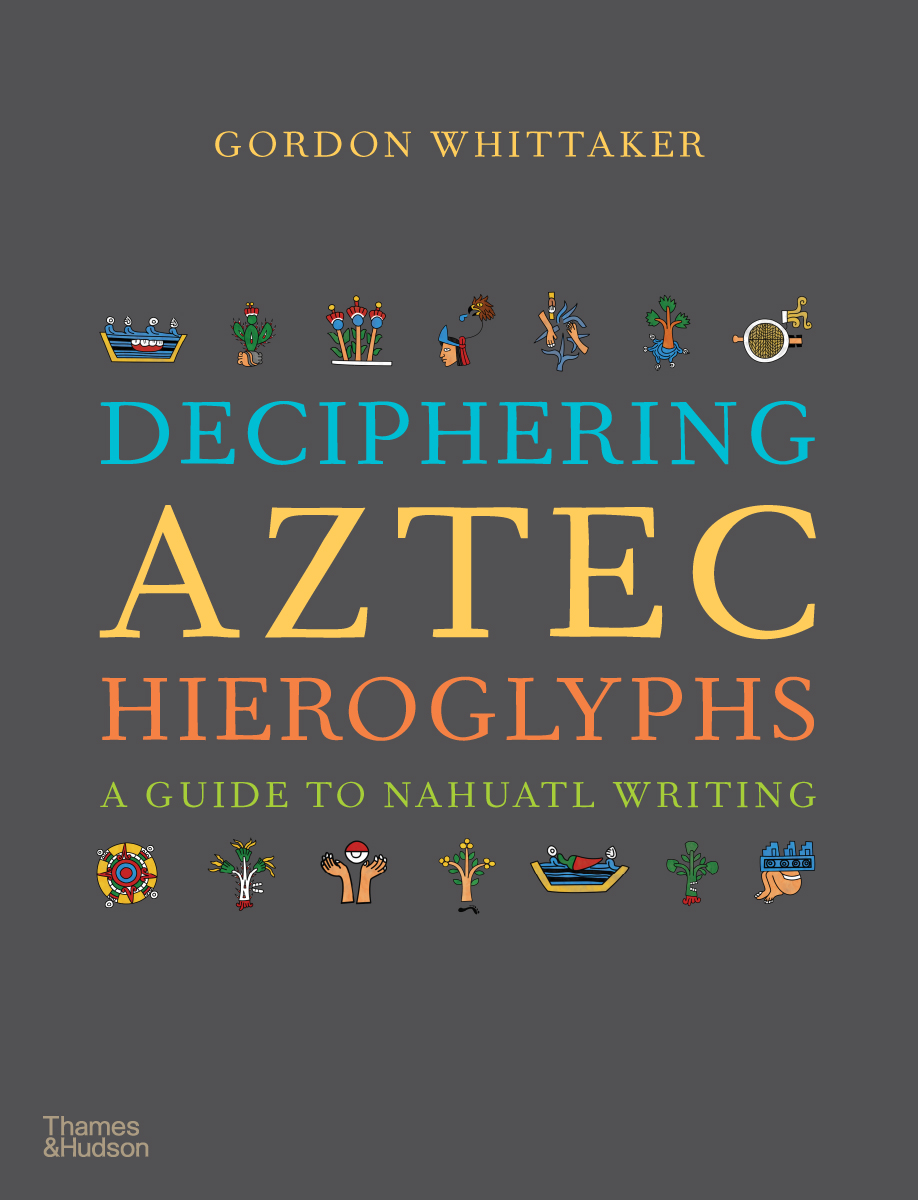

Gordon Whittaker is Fiebiger Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Gttingen, where he has held joint positions in the Institute of Ethnology and the Department of Romance Philology. He has written extensively on Aztec language, writing and civilization. His areas of specialization are Linguistic Anthropology and the Anthropology of the Americas.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Reading the Maya Glyphs

Michael D. Coe and Mark Van Stone

Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs

Michael D. Coe, Javier Urcid and Rex Koontz

The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec

Mary Ellen Miller

An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya

Mary Miller and Karl Taube

Be the first to know about our new releases, exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

Contents

| |

As a supreme cultural achievement, writing has fascinated and transformed societies from its very beginnings in the mid-fourth millennium BC down to the present day. Three of the four indisputable hearths of early writing systemsMesopotamia, Egypt, and Chinahave been well studied and a sizable body of literature, academic and general, is available on each. Younger than the other centers of civilization, Mesoamerica has been the least studied and continues to evoke mystery. Indeed, its very status as a birthplace of writing has only been fully recognized in the last fifty years, following the breakthrough in the decipherment of Maya glyphs in the 1970s. Even now, comparative studies of writing and handbooks on writing systems devote scant attention to Mesoamerica. The Maya script has finally begun to attract the interest of comparativists, and literature on the subject has been growing incessantlyunlike the Aztec script, on which not a single book has been published. It is this gap that the present volume intends to fill, unlocking the mysteries of Aztec writing for a wide readership for the first time.

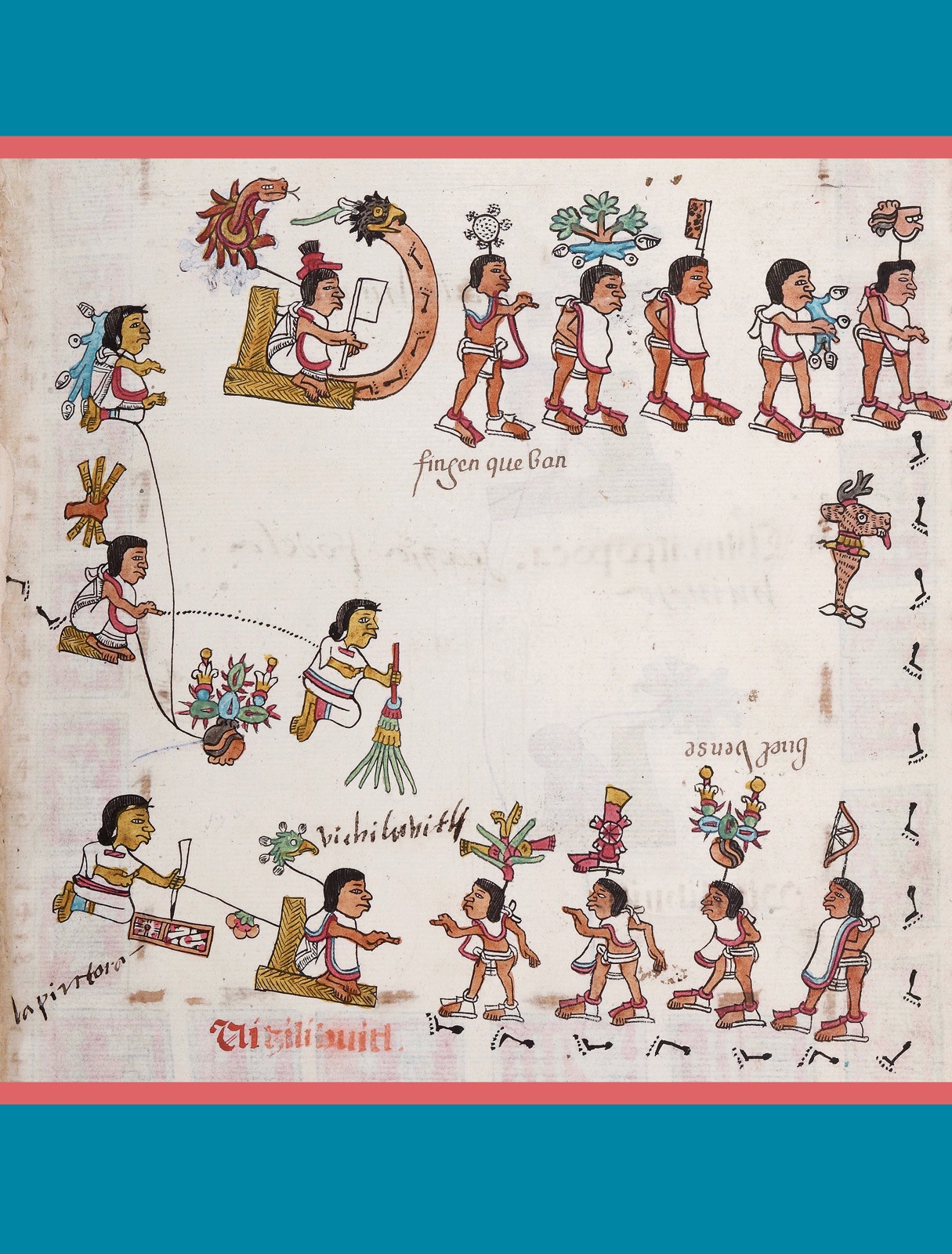

The Aztec writing system is actually one of several that developed in Mesoamerica in Prehispanic times. Zapotec writing was already flourishing in the 1st millennium BC, but the small number of known inscriptions has unfortunately made decipherment all but impossible to date. The same may hold true for the Isthmian script of the 1st millennium AD, although would-be code-breakers have more, and longer, texts to work with. And yet a full-fledged writing system with a more than adequate corpus has been hiding in plain sight for some 500 yearsthe Nahuatl-language hieroglyphic script that came into bloom in the Aztec Empire and continued to evolve even after the cultural upheaval and societal horrors of the Spanish conquest and its aftermath, only to lose its vibrancy in the waning years of the 16th century.

This book itself began with colorful images and signs, as a series of presentations and workshops in Europe and the United States from 2001 onwards. The research behind it has a somewhat longer history. It began when my father, forgetting that his ten-year-old son was actually interested in Romans, not Aztecs, brought home a comic narrating Bernal Daz del Castillos vivid account of the Conquest of Mexico (the Aztec capital, also known as Mexico Tenochtitlan). From this grew a love for all things Aztec. Practice in decipherment followed, when as a schoolboy, now sixteen, I was allowed into the basement of Sydneys Mitchell Library to retrieve the nine ponderous volumes of Viscount Kingsboroughs Antiquities of Mexico that I had requested to see, but the librarian was in no condition to carry. Discovering in it a beautiful hand-painted reproduction of the Codex Mendoza, I spent my spare hours thereafter comparing hieroglyphs with their Spanish glosses and trying to figure out how the writing system worked.

Later, I was fortunate to track down the Anderson and Dibble edition of Book 10 (the only volume available to me) of the Codex Florentinus, which had been compiled in the late 16th century under the editorship of Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagn. Since the published text was bilingual (Nahuatl with an English translation), I went to work comparing the structure of the Nahuatl words with their English equivalents, and in so doing gained my first experience with the Nahuatl language. Soon after, in 1968, I plucked up my courage and wrote to the leading specialist in Mexico, ngel Mara Garibay, for advice on my Nahuatl analysis, not realizing that he had died just a few months earlier. His student, Alfredo Lpez Austin, today Mexicos foremost expert on Mesoamerica, very kindly replied, taking the time to gently correct my Nahuatl, offer me encouragement, and guide me towards the best tools for further study of the language.

Some three years later, as a freshman at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, I was given a printout of a microfilm copy of the Codex Vergara by John Glass, who had compiled a catalogue of so-called pictorial manuscripts for the multi-volume Handbook of Middle American Indians. It was this codex, and John Glasss kindness, that led eventually to the making of this bookthe culmination of half a century of careful, forensic study. The decisive stimulus in writing the volume came from my former Yale doctoral advisor, mentor, and dearest of friends, Michael D. Coe, who recommended me to Thames & Hudson and was a constant source of encouragement right up to his untimely death in 2019.

One would think, given the spectacular forms and colors of Aztec hieroglyphs (dubbed glyphs for short), that scholars would have been attracted to them like bees to honey, but the extraordinary fact is that no handbook of writing has devoted more than a page or so to the subject and most neglect even to mention the existence of the Aztec script, let alone its characteristics. This is the first book ever written on the writing system of the Aztec Empire, and indeed of Nahuatl writing as a whole. Its objective is as much to dispel misconceptions about the nature of Aztec writing as to reveal the patterns, characteristics, and genius of the system. The oversimplifications that were inevitable in explanations for colonial-period learners have also led today in some quarters to the assumption that, in its basic make-up, Aztec writing could hardly match, let alone exceed, in complexity and sophistication the finely honed system fashioned centuries earlier by the Maya; and indeed, to a lack of recognition that the hieroglyphs enshrined in Aztec and other Nahuatl manuscripts are actually elements of true writing. However, I hope it will become clear that the Nahuatl system has a number of surprises in store for students of writing. On the one hand, its multimodal and multifunctional approach to writing, freely incorporating aspects of iconography (such as iconicity, size, proportion, orientation, and color) in writing in a manner similar to the techniques of modern advertising; and on the other, its unparalleled flexibility in the way it derives phonetic sign values (that is, sounds) from word signs.

Next page