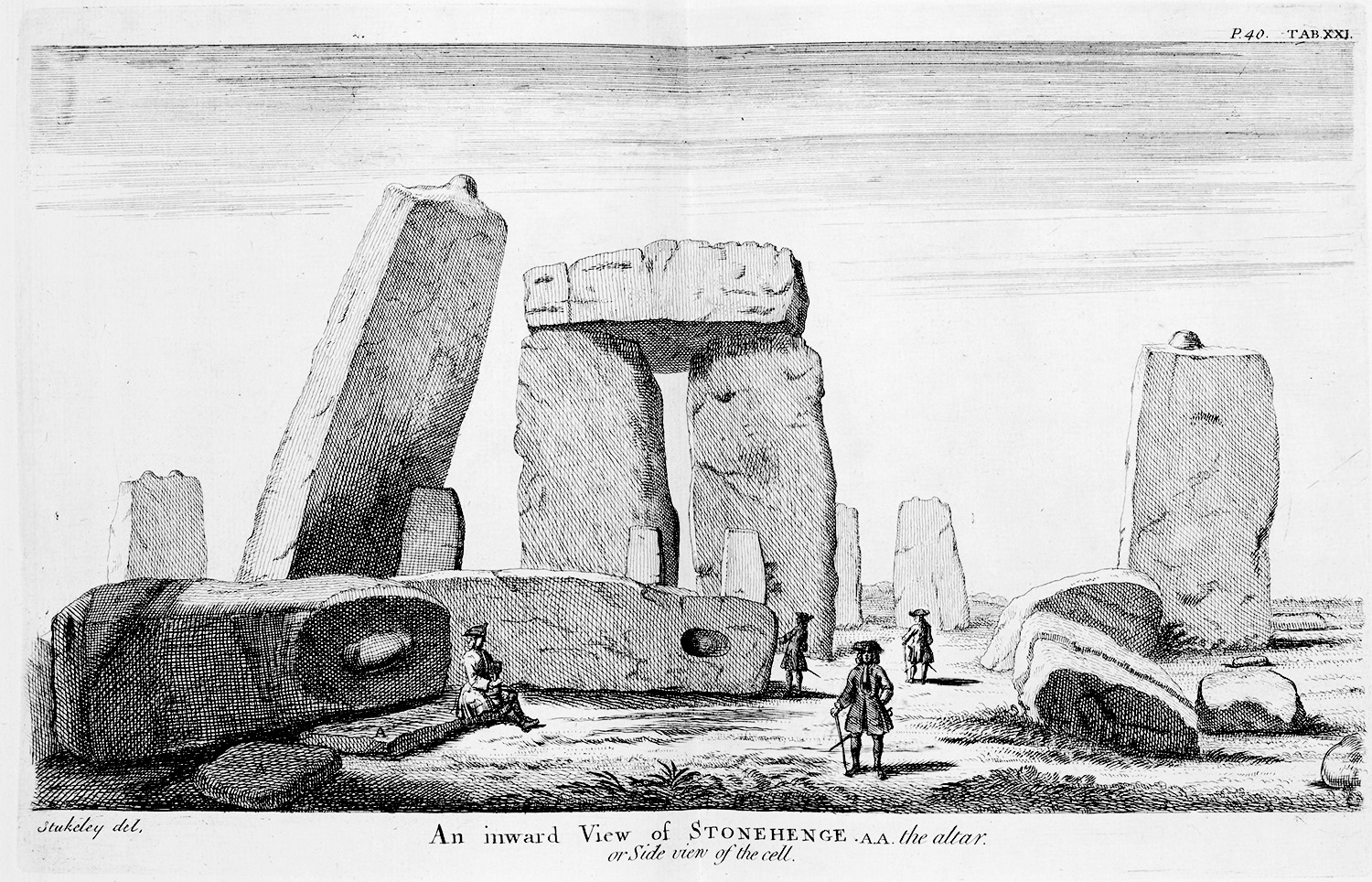

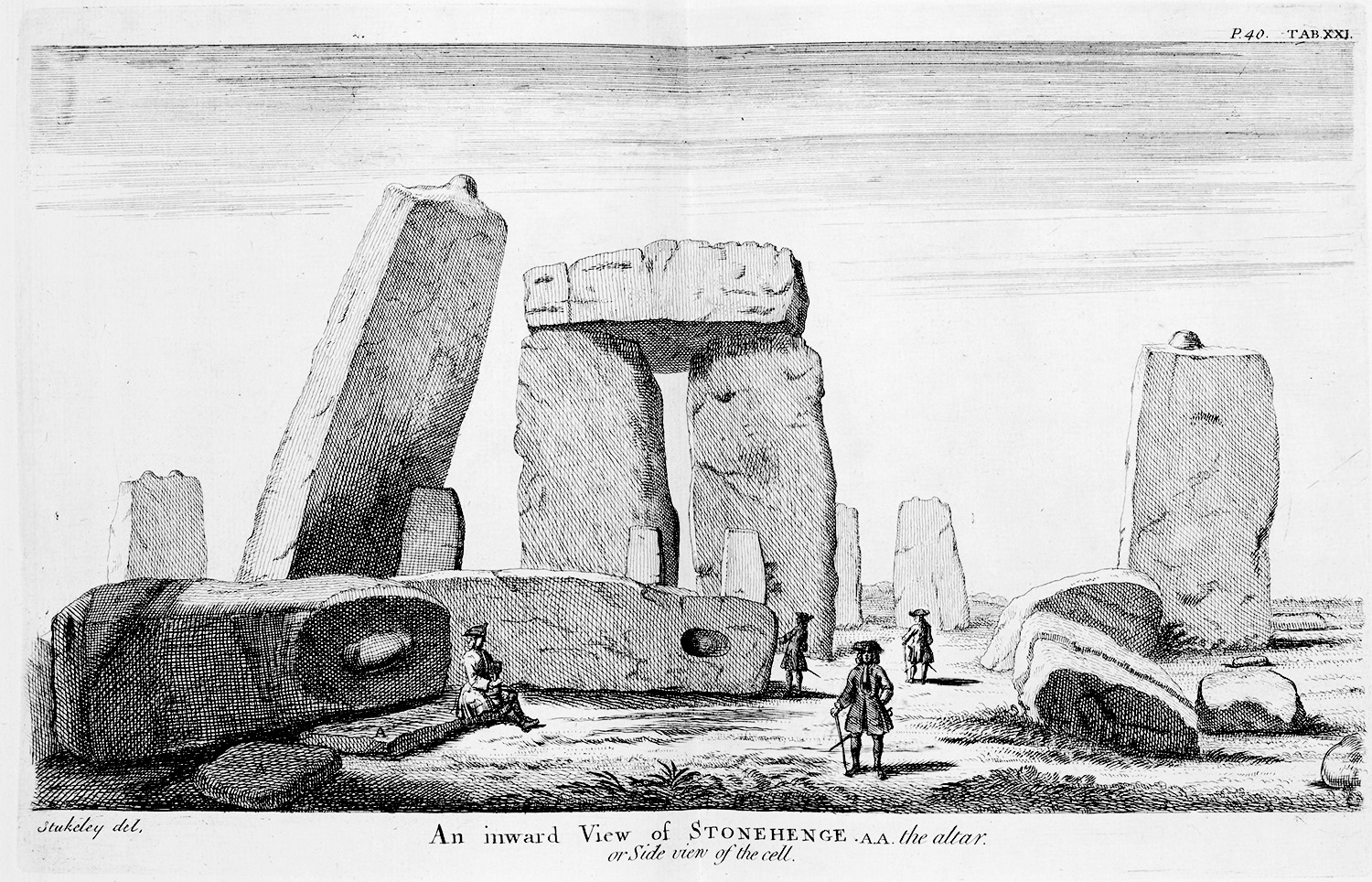

Drawing of one of the Stonehenge trilithons by William Stukeley (16871765). Stukeley had the privilege of studying the prehistoric sites of Stonehenge and Avebury before the ancient earthworks were scoured away by the modern plough.

For Gwyn

About the Author

David Miles has excavated professionally in Britain for over thirty years, becoming Director of the Oxford Archaeological Unit in 1987 and Chief Archaeologist of English Heritage in 1999, and has also worked on projects as far afield as Canada and the West Indies. His academic posts have included Research Fellow of the Institute of Archaeology, Oxford University; Associate Fellow of Kellogg College, Oxford; and Associate Professor at Stanford University. For ten years he was Archaeological Advisor to the Bishop of Oxford. Alongside the numerous excavation and survey reports he has published over the course of his career, he has written many books for the general public, including Introduction to Archaeology (Ward Lock) and The Tribes of Britain (Weidenfeld & Nicolson). Since retiring in 2009 he splits his time between his home in the Cvennes, southwest France, and Blackheath, London.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Stonehenge Complete

The Megalithic Monuments of Britain and Ireland

Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods

atalhyk: The Leopards Tale: Revealing the Mysteries of Turkeys Ancient Town

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

Preface

The human species requires not only a prodigious space of time, but likewise a happy concurrence of circumstances before they can raise themselves above animal life.

VOLTAIRE, 1777

This book is about how and why, from about 12,000 years ago, humans in Western Asia changed their way of life from foraging to farming, and how this transformation spread across Europe to the British Isles by about 4000 BC. Where did the new ideas, techniques, domesticated plants and animals come from? What difference did this transformation make to how people lived, to their population, their impact on the landscape and environment, their diet, social organization, beliefs and monuments, and attitudes to the living and the dead? And how has all this impacted upon us today?

Since our ancestors split from the chimpanzee line, seven million years ago, hominins developed from largely vegetarian forest dwellers to upright-walking inhabitants of the African savannah. By about one million years ago, human ancestors had evolved into large, fierce, omnivorous mammals near the top of the food chain, the only ones that did not depend upon big teeth and sharp claws for their survival. Instead, our ancestors developed increasingly big brains and subtle minds, an ability to cooperate, collaborate with, or even deliberately mislead their fellows through communication skills and speech, and ultimately language. Hominins made increasingly complex tools, controlled fire, cooked food and made protective clothing. Modern humans from about 100,000 years ago began to think symbolically, and created music, stories, art and religious beliefs.

Our ancestors lived in small-scale, but often interlinked, communities and had an ability to spread their kind and ideas across most of the planet, adapting to every environment except Antarctica. From their original homeland in Africa, hominins moved north and east at least 1.7 million years ago. After 60,000 years, Homo sapiens moved out of Africa and rapidly colonized the world. Humans learnt to cope with the cold and adapted genetically: a few of the new northerners even developed pale skin, blue eyes and fair or red hair. It was just as well. Later hominins, especially Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, had to adapt to successive glacial periods and dramatic changes of climate.

Twelve thousand years ago, all human beings depended for food upon gathering wild plants and hunting or scavenging wild animals. Then the world warmed. The climate has stayed relatively stable ever since, although in 2013/14 the USA experienced one of its coldest winters on record and Britain, battered by gales, had its wettest winter since 1766. The waters of the flood were upon the Earth. This is part of a process of global warming and environmental change set in train by our ancestors. Nevertheless, farming developed in what is, by the alarming standards of the past, a period of benign climate.

Gradually, the relationship between humans and some plants and animals changed. Humans cultivated plants selectively and reared a narrow range of animals. The varying selection pressures encouraged domestication, which consisted of genetic and morphological changes to these plants and animals. They became entangled, increasingly dependent upon each other. Many humans like to think that they domesticated previously wild species for their own benefit that they have dominion over them, in the words of Genesis. Alternatively, domestication could be seen as a two-way process: plants, such as wild grasses, and animals, notably sheep, cattle and pigs, hitched a ride with mobile and adaptable humans. As a result, many of the species involved for example, dogs, cattle and cereals were subject to genetic change. We humans also changed, to some extent genetically, but most of all culturally. The move to farming was, arguably, the most significant shift in human history, which launched the expansion of the human population, the surpluses of food that supported civilization, the growth of towns and a dramatic increase in material goods, particularly objects of symbolic importance. We became the dominant species in the world; the most creative, the most destructive and, for a big beast, incredibly numerous.

The process of domestication speeded up about ten millennia ago. Over the next few millennia most human beings adopted some form of agriculture or became herders. A species of hunter-gatherers, numbering perhaps seven million worldwide 11,000 years ago, was transformed into farmers and then, thanks to the success of farming, into city dwellers. In the early 21st century our numbers topped seven billion. Our impact on planet Earth is now so great that the Holocene, the wholly recent epoch that began 12,000 years ago with the end of the Ice Age, has given way to the Anthropocene the age of humans.

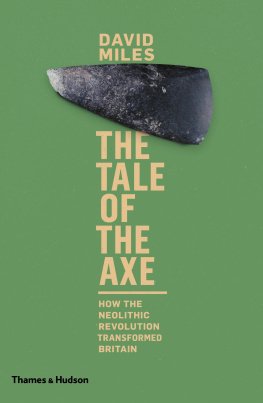

Archaeologists in the 19th century recognized a shift in prehistoric stone technology, which produced ground or polished stone axes they labelled this the Neolithic, or New Stone Age. For thousands of generations, hominins (who included the ancestors of Homo sapiens) had chipped suitable stone to form tools, including axes held in the hand. The distinctive new axes of the Neolithic were ground to give a smooth, polished surface. They could be hafted with wooden handles to make a proficient chopping tool, and sharpened more efficiently. These axes appeared at the same time as farming communities developed in the Near East and then later in Europe; the polished stone axe became an icon of what in the 20th century was termed the Neolithic Revolution: the appearance of farming. In the Neolithic, humans established settled communities, farmsteads, villages and towns, and began to store food, increasingly manufacture pottery and build monuments. The mid-20th-century prehistorian Vere Gordon Childe and his many successors have presented this as a landmark in human history, a revolution comparable with the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. We now know that the story is more complex, but nevertheless this was a turning point for humanity from which there was no going back. If there was a Neolithic Revolution, it is still continuing.