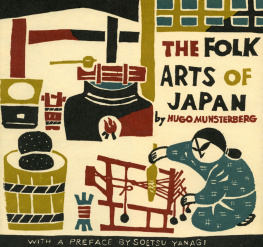

DR. HUGO MUNSTERBERG received his Ph.D. in Oriental art from Harvard. He has taught at Wellesley College, Michigan State University, International Christian University in Tokyo, and presently teaches at New York State University College at New Paltz. He is the author of many published books, including: The Folk Arts of Japan; The Arts of Japan: An Illustrated History; The Art of the Chinese Sculptor; The Ceramic Art ofJapan: A Handbook for Collectors; Zen & Oriental Art, and Chinese Buddhist Bronzes.

Seated Bodhisattva, Wall Painting in the Kond (Golden Hall). Nara period.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

GENERAL HISTORIES OF JAPANESE ART

Hshu Minamoto. An Illustrated History of Japanese Art. Kyoto, 1935.

(Good treatment of painting and sculpture but no discussion of architecture and crafts.)

Noritake Tsuda. Handbook, of Japanese Art. Tokyo, 1935.

(Good general discussion of all phases of Japanese art; especially useful for listing the famous sites and collections.)

Pageant of Japanese Art, 6 vols, (edited by Staff Members of the Tokyo National Museum) Tokyo, 1952-54.

(This is the most recent and most complete discussion of Japanese art available. The text is written by leading Japanese authorities and there are numerous excellent plates.)

Langdon Warner. The Enduring Art of Japan. Cambridge, 1952.

(Popular introduction into Japanese art by one of America's leading scholars in this field.)

JAPANESE PAINTING

Lawrence Binyon. Painting in the Far East (4th ed.), London, 1934.

(Well-written but rather outdated discussion of the various schools of Japanese painting, and few illustrations.)

Henry P. Bowie. On the Laws of Japanese Painting. London, 1911; reprinted New York, 1951.

(A detailed technical discussion of traditional Japanese ink-painting, with many diagrams.)

Arthur Morrison. The Painters of Japan. 2 vols. London, 1913.

(Very much outdated and poorly illustrated but still the most complete discussion of this subject by a Westerner.)

Hugo Munsterberg. The Landscape Painting of China and Japan. Tokyo, 1955.

(A complete discussion of this specialized branch of Far Eastern painting.)

Pageant of Japanese Art, Vols. I-II. Tokyo, 1952,

(This is the most complete and up-to-date discussion of Japanese painting, although it omits the modern period entirely.)

Kenji Toda. Japanese Scroll Painting. Chicago, 1935.

(Very good and scholarly discussion of this important phase of Japanese art with some good color reproductions and Japanese references.)

JAPANESE COLOR PRINTS

L. Binyon and J. J. Sexton. Japanese Color Prints. London, 1923; reprinted New York, 1955.

(Excellent discussion of the ukiyo-e school arranged chronologically. Good plates.)

Arthur D. Ficke. Chats on Japanese Prints. London, 1916; reprinted several times.

(Popular but very good and learned treatment of the subject with artists' seals.)

Shizuya Fujikake. Japanese Wood-Block Prints. Tokyo, 1954.

(A small volume in the Tourist Library particularly useful in dealing extensively with modern prints.)

James Michener. The Floating World. New York, 1954.

(Lively and well-done discussion by the famous novelist. Poor plates.)

Waldemar von Seidlitz. History of Japanese Color Prints. London, 1910.

(A pioneer work by a German expert, but still useful.)

Basil Stewart. Subjects Portrayed in Japanese Color Prints. London, 1922.

(Very learned and useful work giving a clue to the subjects of ukjyo-e prints.)

JAPANESE SCULPTURE

Japanese Sculpture, 6 vols, (by various editors and photographers) Tokyo, 1952.

(Collection of magnificent photographs with brief text dealing with Japanese sculpture from the prehistoric period to the Kamakura age.)

Pageant of Japanese Art, Vol. III. Tokyo, 1953. (Scholarly discussion and excellent plates.)

Langdon Warner. The Craft of the Japanese Sculptor. New York, 1936. (Good discussion of the technical aspects of Japanese sculpture.)

JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE

Jir Harada. The Lesson of Japanese Architecture (Rev. ed.), London, 1954.

(Many good pictures of Japanese houses but brief text.)

Pageant of Japanese Art, Vol. VI. Tokyo, 1954.

(Scholarly discussion and excellent plates.)

A. L. Sadler. A Short History of Japanese Architecture. Sidney, 1941.

(A scholarly discussion based on Japanese sources but illustrated only by line-drawings.)

Alexander Soper. Buddhist Architecture in Japan. Princeton, 1942.

(A definitive scholarly work but not for popular consumption.)

Bruno Taut. Houses and People of Japan. Tokyo, 1937.

(Interesting discussion of Japanese domestic architecture by one of Europe's leading modern architects.)

Tetsur Yoshida. The Japanese House and Garden. New York, 1955.

(Excellent discussion of Japanese houses by a Japanese architect. Magnificent plates.)

JAPANESE CRAFTS

H. L. Joly. Japanese Sword Guards. London, 1910.

(A very scholarly catalogue of a famous tsuba collection.)

G. Koizumi. Lacquer Work. London, 1923.

(A practical guide to the art of Japanese lacquer. Poor illustrations.)

Tadanari Mitsuoka. Ceramic Art of Japan. Tokyo, 1949.

(A small but excellent volume in the Tourist Library. Poorly printed.)

Yuzuru Okada. Netsuke, A Miniature Art of Japan. Tokyo, 1951.

(A small but good volume in the Tourist Library.)

Okada, Koyama, and Hayashiya. Japanese Ceramics. Tokyo, 1954.

(Only brief English text but many magnificent plates.)

Pageant of Japanese Art, Vols. IV-V. Tokyo, 1952 and 1954.

(These volumes deal with ceramics, metalwork, textiles, and lacquer. Scholarly discussion and excellent plates.)

A. D. Howell Smith and A. Koop. A Guide to Japanese Textiles, 2 vols. London, 1919-20.

(A scholarly and detailed catalogue of Japanese textiles in the Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Setsu Yanagi. Folk, Crafts in Japan. Tokyo, 1949.

(A brief but excellent introduction into Japanese folk art with some plates.)

The Prehistoric Art of Japan

A LTHOUGH Japan has been inhabited for at least five thousand years, the Japanese as we know them today have probably only existed for about half that time. Who they were and where they came from are questions about which archaeologists and historians have never been able to agree. Their racial strains are varied, but it is generally recognized that the three chief components are Mongoloid, Malayan, and Caucasian. It is also agreed that waves of immigrants from the mainland, especially from China and Korea, came to Japan during the course of the neolithic period. It seems unlikely that Japan was settled before this, though archaeological discoveries may substantiate the theories of those who believe that it was inhabited during paleolithic times.

The Kojiki and the Nihonshokj, two sacred books compiled in the eighth century of our era, record myths which tell of the origin of the universe and of the Japanese people. These stories are confused in the extreme. A fantastic number of kami are created, spirits of every conceivable kind, such as the three Kami called "Shore Distant," "Wave-Edge-Shore-Prince," and "Intermediate-Shore-Direction." The creation myth, retold by Post Wheeler in his book The Sacred Scriptures of the Japanese, is as follows:

Of old time the Sky and the Earth were not yet set apart the one from the other nor were the female and male principles separated. All was a mass, formless and egg-shaped, the extent whereof is not known, which held the life principle. Thereafter the purer tenuous essence, ascending gradually, formed the Sky; the heavier portion sank and became the Earth. The lighter element merged readily, but the heavier was united with difficulty. Thus the Sky was formed first, the Earth next, and later Kami were produced in the space between them.