BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAYS

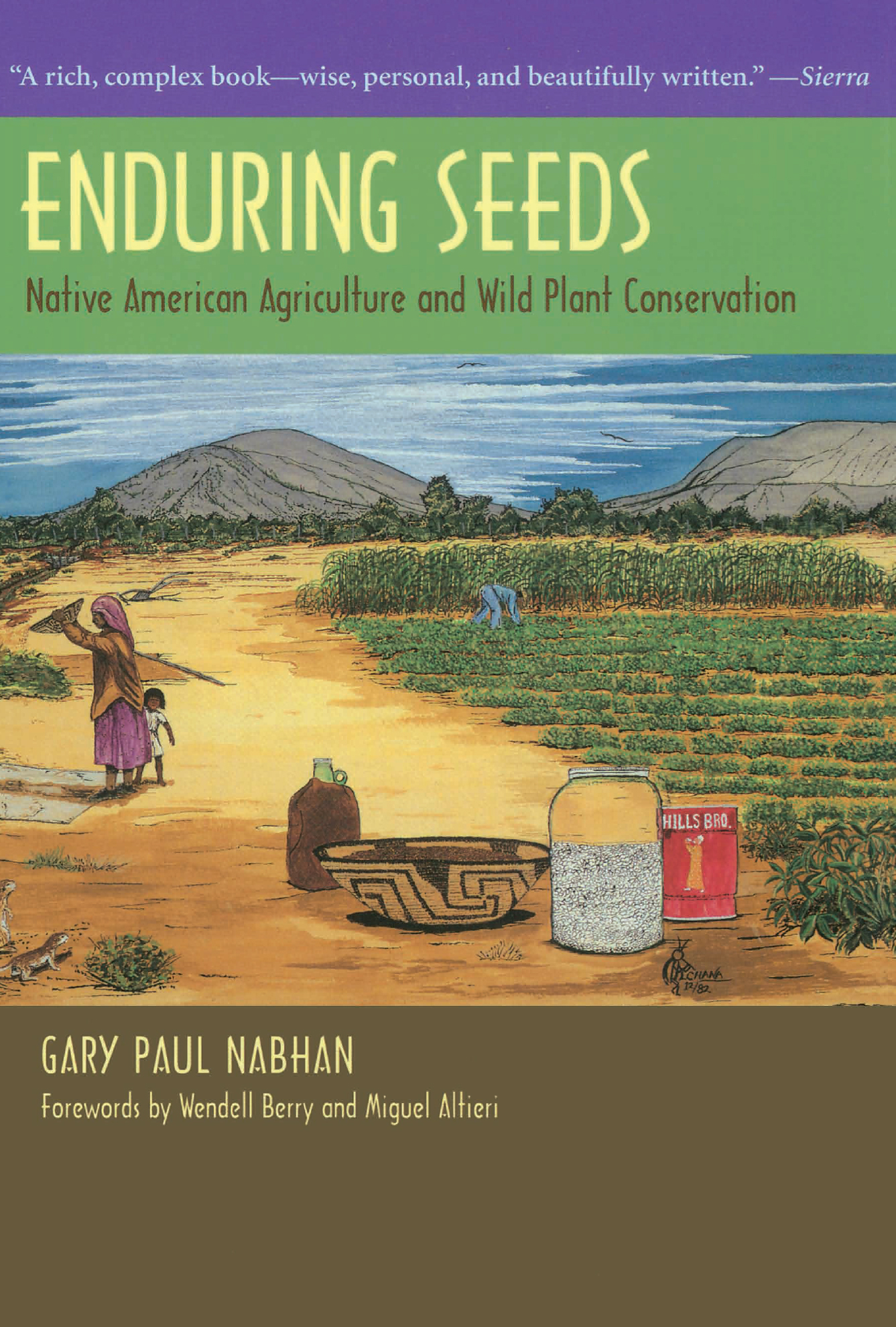

Prologue: Enduring SeedsThe SacredLotusandthe Common Bean For an introduction tothe longevity of seeds, see my 1978 essay on the folklore and science of archaeologicalseeds, and the 1986 review by Roos. With regard to how the loss of adapted seedstockshas made agriculture more genetically vulnerable, the National Research Councils1972 report remains a classic, although I am currently assisting Garrison Wilkes,Ivan Buddenhagen, and Donald Duvick in a new interpretation/edition. Other worksconsulted or quoted in the prologue include Adams (1977), Conard and colleagues (1984),Kaplan (1981), Jarvis (1908), Lewandowski (1988), Libby (1954), Ohga (1923 and 1926),Priestly and Posthumus (1982), Ramsbottom (1942), Wester (1983), and contributorsto Whealys 1986 compilation of Seed Savers Exchange correspondence and history.

Chapter One: The Flowering o fDiversity The best overview of biological diversity,its importance and endangerment, is the 1988 anthology edited by E. O. Wilson andFrances Peter; it is an outgrowth of presentations given at the National Forum onBio Diversity held in Washington, D.C., in 1986. It includes eloquent commentariesby scientists, conservationists, poets, and philosophers. Many of the concepts relatingto the historic diversification of flowering plants were reviewed by Philip Regalin his 1977 article on the evolution of flowering plant dominance. The role of Pleistocenemegafauna in shaping American landscapes, and the possible role Native Americansplayed in extirpating these large animals are reviewed in the 1986 anthology editedby Paul S. Martin and Richard G. Klein. I discuss the relationship between theseextinctions and the initiation of intensive food production in the New World in atechnical paper in press, inspired by Alford (1970), and Janzen and Martin (1982).The literature on Florissant fossil beds is interesting reading in and of itself.See Saenger (1982) for a popular account, or Leopold and MacGinitie (1972) for recentscientific ruminations. Other literature cited or interpreted includes Beach (1982),Beck (1976), Bordes (1968), Crosby (1986), Crosby and Raven (1985), Charles Darwinin Francis Darwin and Seward (1903), Hunter and Aarssen (1988), Kruckeberg (1986),MacGinitie (1953), Martin (1986), Pellmyr and Thien (1986), Lewis and Clark in Sweet(1962), Tifney (1984), Toledo (1987), and Whittington and Dyke (1986).

Chapter Two: Diversity Lost: The WetandtheDry Tropics

Anyone unacquainted with tropical conservation issues should first partake of thepopular books by Norman Myers (1984) and Catherine Caulfield (1985). To counterbalancetheir preoccupation with the wet tropics, I recommend Daniel Janzens 1988 essayon the dry tropics in Bio Diversity. With regard to the Guatemalan deforestationproblems, I have relied heavily on the excellent reports by Nations and Komer (1984),Wotowiec and Martinez (1984), and Berganza (1987), supplemented by my own brief fieldtrips there with the Peace Corps. With regard to the transition from the desert tothe tropics, I have drawn on Wiseman (1980). To compare genetic resources of wetand dry tropics, I have used data from Esquinas-Alcazar (1988) and from my 1986 essayprinted in Annals of Earth Stewards and in Earth First!. Other articles drawn uponfor this chapter include Creech cited in Miller (1973), Givnish cited in May (1975);Janzen (1986), Maslow (1987), Prescott-Allen and Prescott-Alien (1987), Simberloff(1987), and various news reports in Science magazine regarding tropical deforestation,especially those of Holden.

Chapter Three: Fields Infusedwith Wildness

This essay evolved out of my 1987 ethnobiology and conservation article, and severallectures. For the discussion of maize-teosinte introgression, it attempts to findsome middle ground between Wilkes (1970), and Doebley (1984); Doebley's unpublishedanalysis of my corn and teosinte samples from Nabogame indicates the probabilityof minor gene flow from teosinte to corn, but certainly not any swamping. I havealso drawn upon the work of Betancourt and Van Devender (1981), Brown (1985), Diamond(1986), Doebley and colleagues (1984), Ehrenfeld (1986), Emslie (1981), Lumholtz(1902), Nabhan and colleagues (1985), Nabhan (1983), Oldfield and Alcorn (1987),Pennington (1969), Vovides (1981), and Winter (1976).

ChapterFour: InvisibleErosion: TheRiseandFallofNativeFarming

This chapter echoes the ornithological treatise set forth by Amadeo Rea in his 1983classic, Once a River. There are few other books which discuss subsistence historiesof particular tribes in sufficient detail with regard to ecological and genetic changes;William Cronons 1983 Changes in the Land is another notable exception. Carlson (1982)has explored historic government policies which discouraged Indian farm ing, andI have questioned other government stances regarding conservation of N ative Americanplant genetic resources in 1985 and 1987 articles. H urt's 1987 history of Indianagriculture in North America was not available to me at the time of researchingthis chapter, but it is nevertheless highly recommended. All of these authors arein agreement that small-scale Indian farming did not die out due to any ecologicalfailure, but because of external economic and social pressures. Other literaturecited or interpreted includes Bohrer (1970), Bureau of Indian Affairs (1988), Cabezade Vaca in Smith (1871), Conard and colleagues (1984), Dobyns (1977), Ford (1981),Doyel (1979 and 1988), Haury (1976), Heiser (1985), Masse (1981), Minckley (1973),Spicer (1962), Smail (1987), Sauer (1977), Yarnell (1977), and Yarnell (in press).I must also acknowledge that The Ballado fIra Hayes written by Peter LaFarge andJohnny Cash goes through my head whenever I think of the Pima Indians losing theGila River; lyrics are used by permission of CBS/Columbia Records.

Chapter Five: A Spirit Earthly Enough: Locally Adapted Crops and Persistent Cultures

This chapter is a drastic revision of my infamous 1983 Kokopelli essay; I no longerthink that the symbol of Kokopelli as a cross-cultural trader of seeds is as keyto crop genetic diversity as is each culture's survival. The best technical paperson crop genetic diversity in cultural contexts are by Altieri and Merrick (1987)and by Oldfield and Alcorn (1987). I have also drawn upon Anderson (in press), Basso(1987), Berry (1981), Betancourt and Van Devender (1981), Brush (1986), Burns (1983),Bell and colleagues (1980), Crosby (1986), Franquemont (1987), Gould (1986), Harlan(1975), Lawton and Wilke (1979), LeBlanc (1985), Nabhan (1979), Nabhan and colleagues(1983), Nations (1984), Spicer (1971 and 1980), Trenbath (1975), Wolfe (1985), andvan Willigen (1981).

Chapter Six: New and Old Ways of Saving: Botanical Gardens, Seed Banks, Heritage Farms,And Biosphere Reserves

An excellent introduction to current grassroots efforts to save rare plants and animalswas edited by the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment in 1986, based onfour commissioned papers, one of which I prepared with Kevin Dahl through NativeSeeds/SEARCH. For this chapter, I have also relied upon discussions by Archibaldin Houseal and colleagues (1985), Barton (1978), Dugelby (1987), Elias (1987), Emmart(1940), Euler (1956), Grossman (1985), Hirth (1984), Nabhan and colleagues (1981),Plucknett and colleagues (1983), Posey (1984), RamrezAcosta (1986), and Whealy(1986).

Chapter Seven: Wild-Rice: The Endangered, the Sacred, and the Tamed

Although not yet available when I was writing and researching this chapter, ThomasVennum has recently published what will surely stand as the classic on wild-riceand native peoples. Jim Meekers extensive literature and field notes on wild-ricewere my touchstones instead. For this chapter, I consulted Danziger (1978), Emeryin Terrell and colleagues (1978), Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission(1987), Jenks (1900), LaDuke (1987), Levi (1956), May and Lyles (1986), Meeker andRagland (1987), Nelson and Dahl (1986), Oelke (1974), Ritzenthaler (1978), San MarcosRecovery Team (1984), Taylor in Danziger (1978), Terrell and Wiser (1975), and Thannum(1987).